A picture by Dalí is worth a thousand words…

Curated by Abigail Wunderle and McKenzie Bengry

Salvador Dalí, known for his paintings, drawings, and even his own writings, was also an illustrator for many books. “Dalí worked in this field of creation so often because, rather than an amusement, the work was a necessity for him. Dalí had to express himself and any medium that allowed him to do so was valid. That was why he never missed an opportunity to work in publishing,” (Dali, a life in books, p.344).

This series of digital exhibitions, broken up into several parts, will focus on illustrations Dalí created for commercial books, some of which are rarely seen. This series will also focus on the symbols Dalí inserts into the illustrations, promoting his own iconography. “Salvador Dalí used symbols repeatedly in his artwork. He was influenced by Sigmund Freud’s idea that dreams can be understood symbolically – where each image has its own interpretation – Dalí approached his work this way” (Dalí Museum-Peter Tush, Curator of Education). Shown here in the book illustrations are the main symbols, as well as other Dalí symbols. Viewers will then be given an opportunity to discover the same symbols in works from The Dalí Museum Collection. The use of these specific symbols shows how Dalí inserts himself throughout his artwork, even in books.

In this last installment, we conclude our online exhibition series on Dali’s commercial book illustrations, but stay tuned for more online exhibitions.

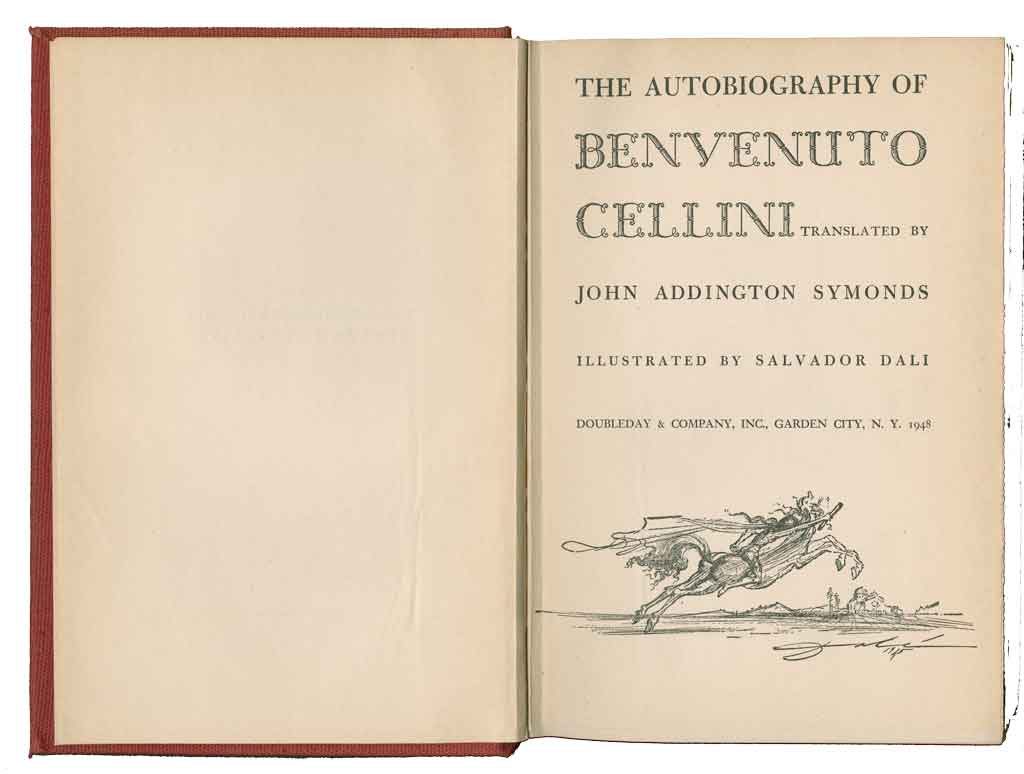

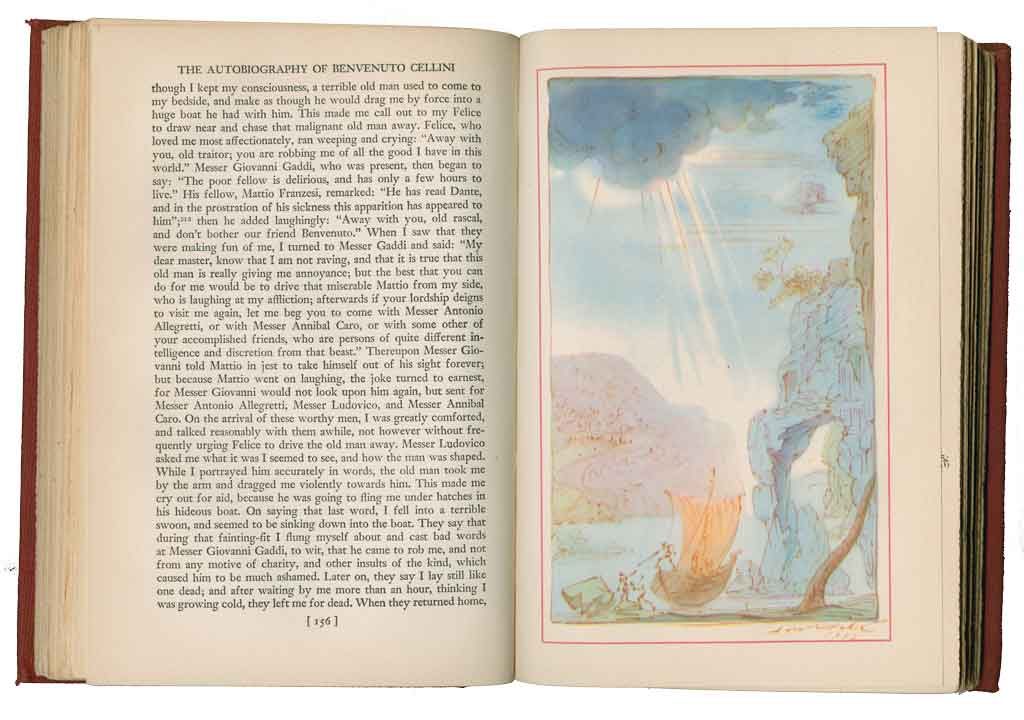

The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini

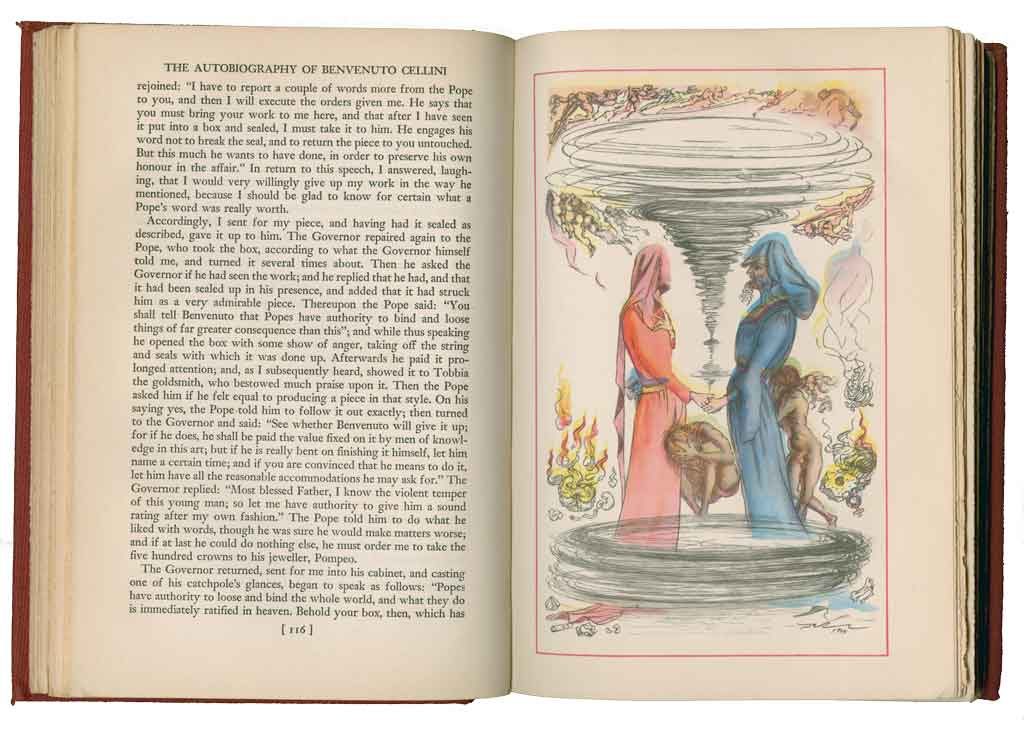

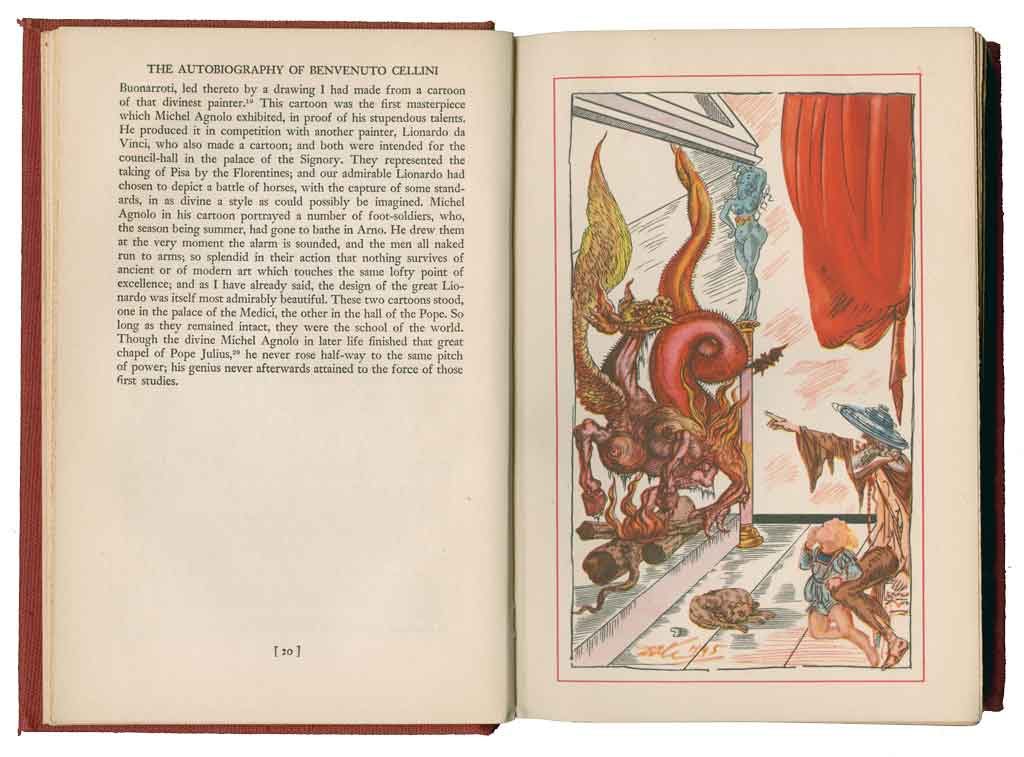

In 1948, while Salvador Dalí was in the United States, he was given a copy of The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini. In a description from Dalí By the Book from 1996: “Dalí illustrated The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, a 16th century Florentine goldsmith, sculptor, and author of one of the world’s greatest autobiographies… It tells of his adventures in Italy and France, his relations with popes, kings and other fellow artists. Famous for his sculptures and his silver and gold work this genuine personality lead a vivid and tumultuous life.”

Feeling inspired by eccentric stories, Dalí created forty-one illustrations for this book (Don Quixote de la Mancha: Illustrado Por Salvador Dalí, p. 77).

Dali’s interest in this book may have “resulted from his [Cellini’s] work as silversmith – we should remember that between 1949 and 1970 Dalí designed his own collection of jewels, which now belong to the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation” (Don Quixote de la Mancha; Illustrado Por Salvador Dalí, p. 78).

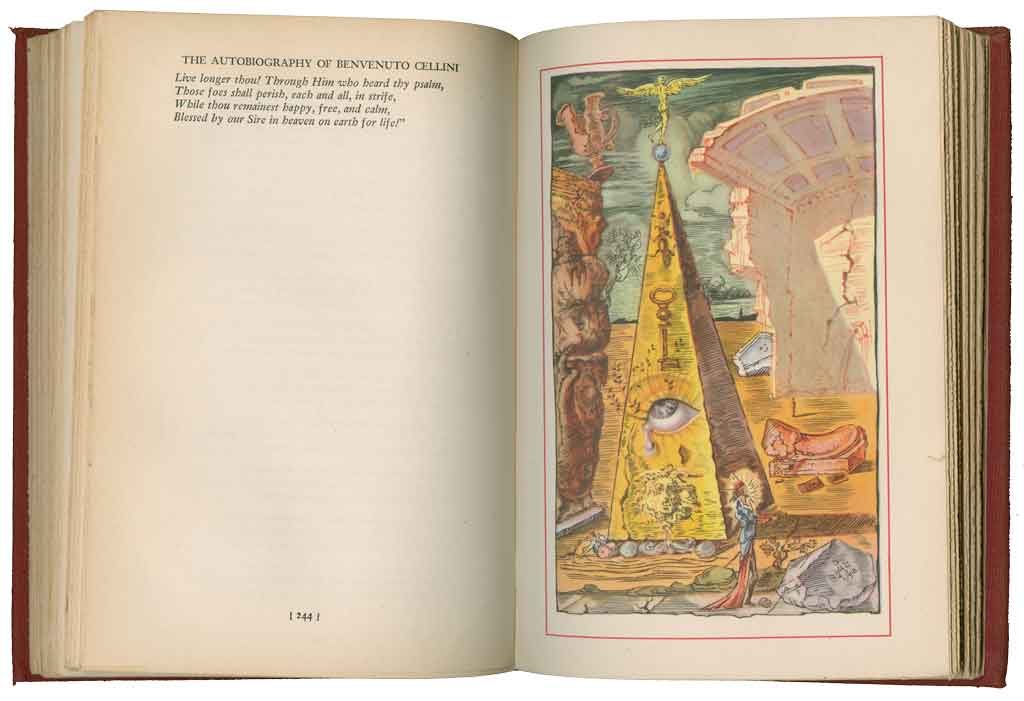

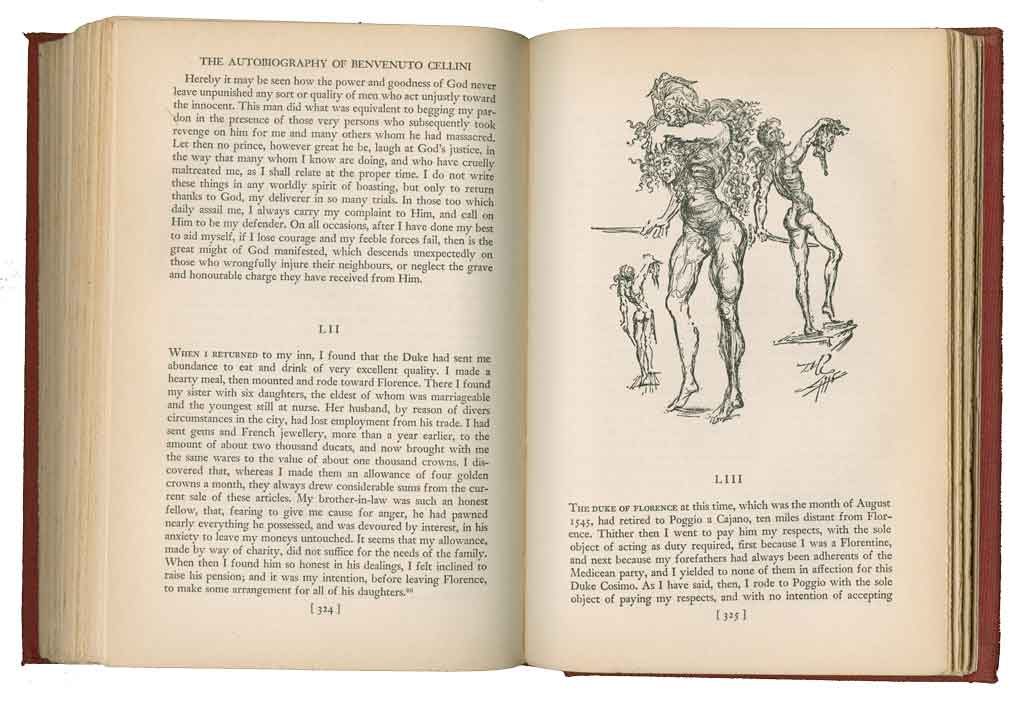

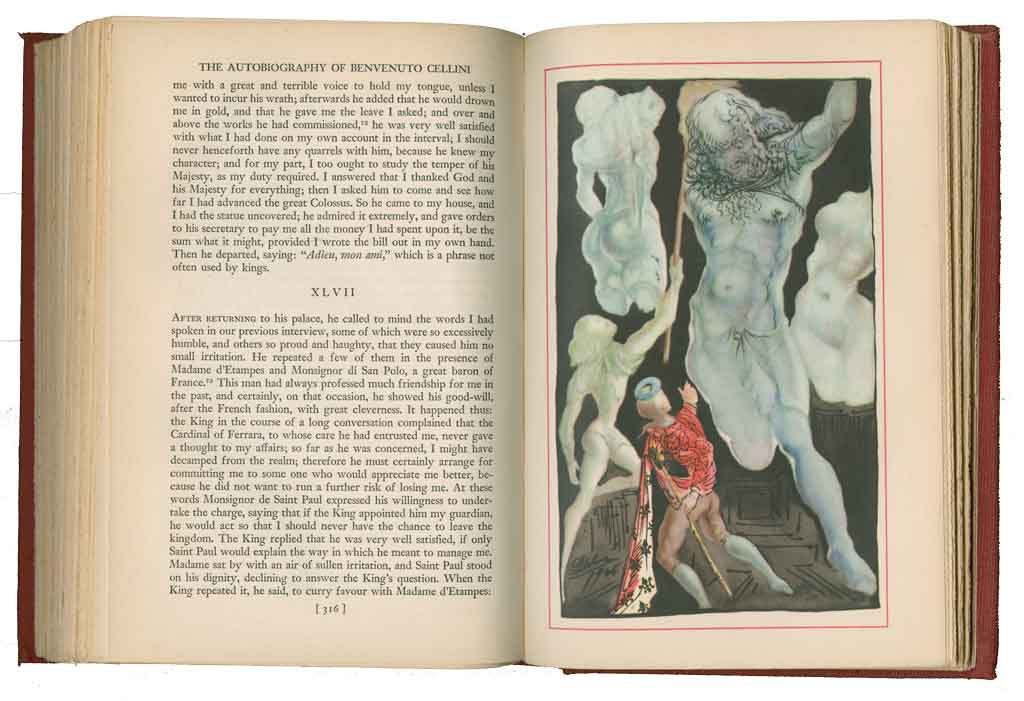

In some illustrations, Dalí takes direct inspiration from Benvenuto Cellini’s own artwork.

Dalí takes inspiration from the text that sits across from his sketch of Perseus and Medusa: “Hereby it may be seen how the power and goodness of God never leave unpunished any sort of quality of men who act unjustly toward the innocent… Let then no prince, however great he be, laugh at God’s justice in the way that many whom I know are doing, and who have cruelly maltreated me….” (324, 325).

“… then I asked him to come and see how far I had advanced the great Colossus. So he came to my house, and I had the statue uncovered; he admired it extremely, and gave orders to his secretary to pay me all the money I had spent upon it, be the sum what it might, provided I wrote the bill out in my own hand. Then he departed saying: “Adieu, mon ami,” which is a phrase not often used by kings.” (316).

Dalí Symbol… The Ant!

Dali’s iconic image of the ant is easily made from his pen, but the creation of the idea was painted by nature herself: “The young Dalí watched in fascination, the decomposition remains of small animals being eaten by ants. This repulsive image carried on through his artwork. They can be seen his drawings, prints and paintings. To Dali, ants were a symbol of death, decay and a decadence” (Dalí Museum).

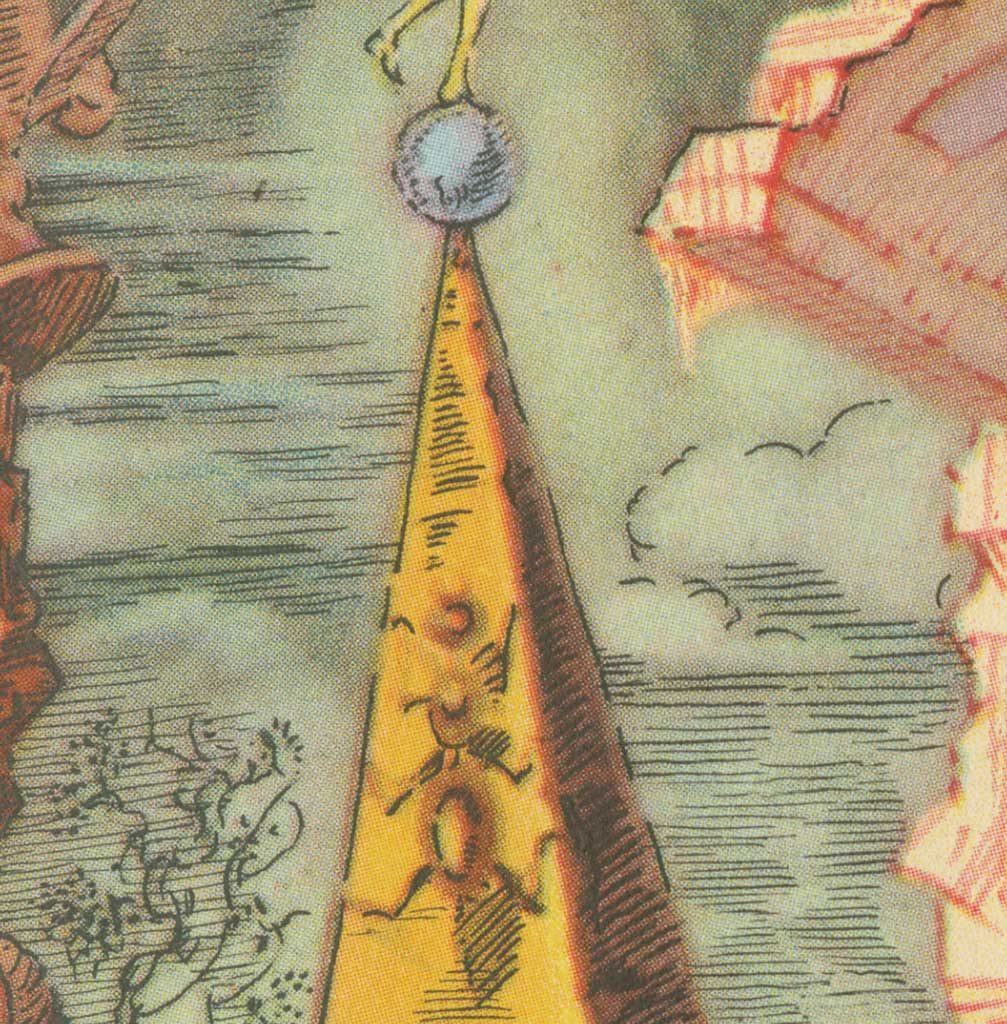

An ant can be seen at the top of the pyramid in the illustration Dalí created for The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini. There are also ants, and often groups of ants, in many of Dali’s paintings including Daddy Longlegs of the Evening – Hope!, Profanation of the Host, The Font, and his gouache Les Fourmis.

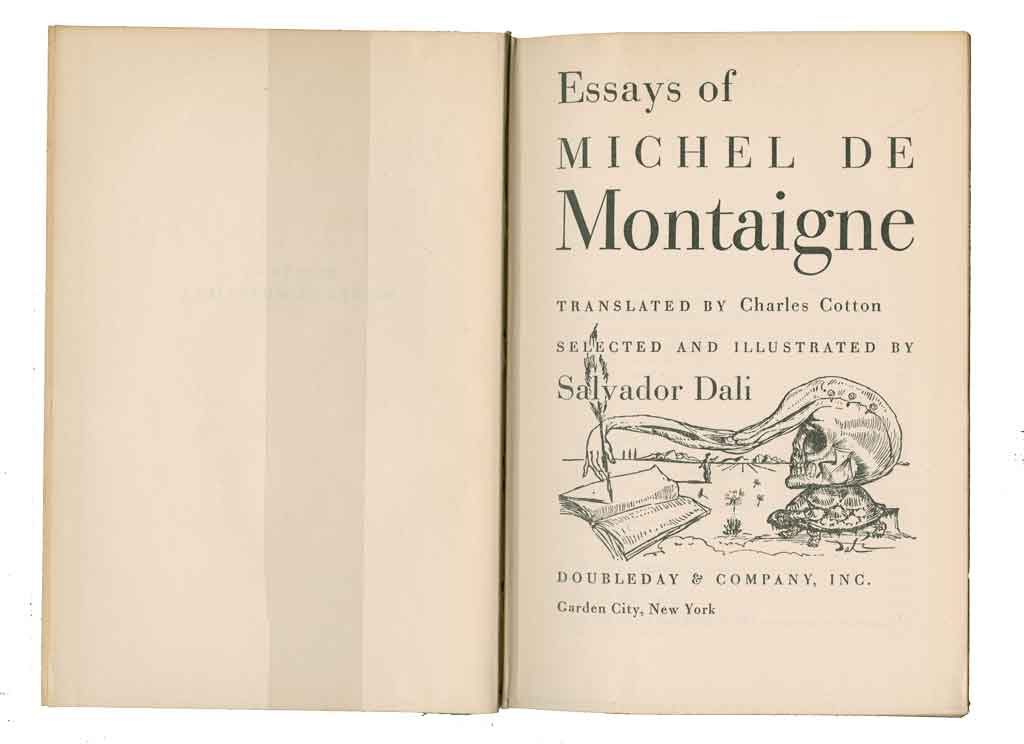

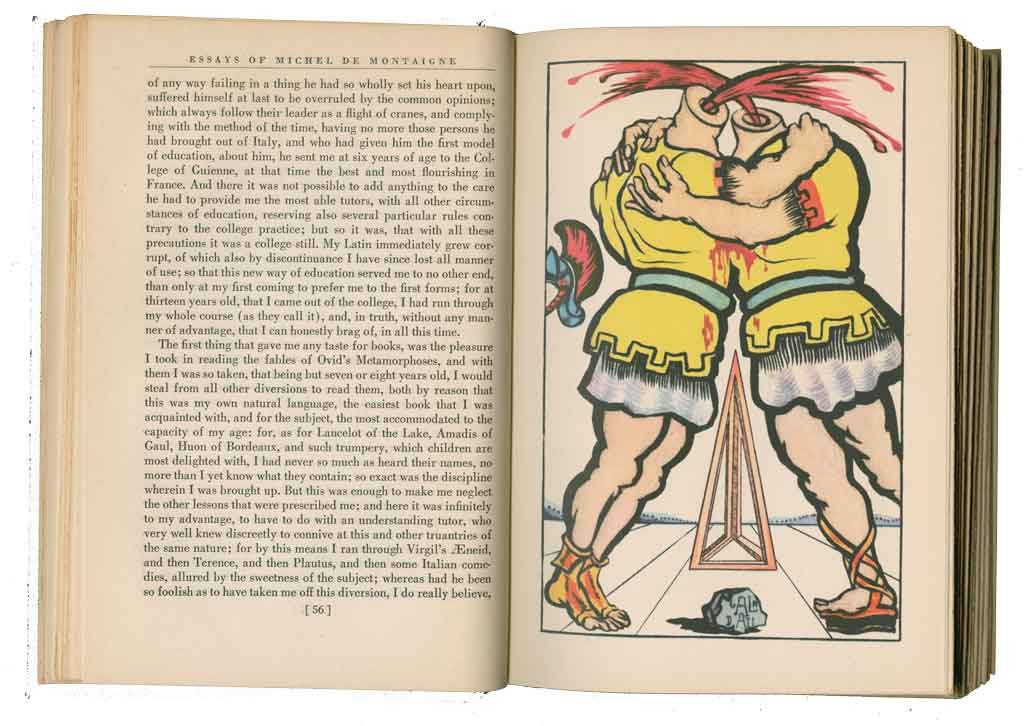

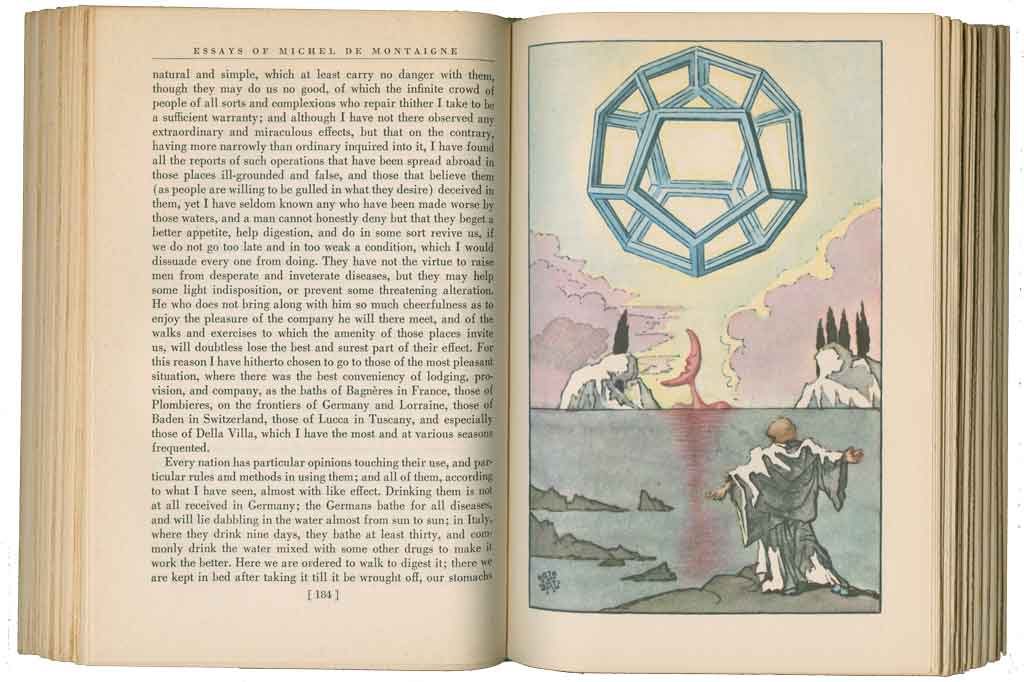

Essays of Michel de Montaigne

“Michel de Montaigne was a French moralist and a creator of the personal essay. His father, kindled by the enthusiasm of the Renaissance, hired an ideal tutor for his son. The tutor spoke only Latin to Montaigne until he was six and had him awakened every morning by music. He became a counselor in the Bordeaux Parlement. In 1571 he retired to his chateau in Dordogne and devoted himself to reading and writing until 1580, when he published the first two books of his Essays. In 1947, Doubleday published a limited edition of Michel de Montaigne’s Essays. Dalí signed all one thousand copies of the edition.” (Dalí By The Book exhibition file, 1996)

Dalí created “thirty-seven works that illustrated his own selection from Montaigne’s Essais,” and “his interest in this book could be due to “the philosopher’s great curiosity about all expressions of mankind,” (Don Quixote de la Mancha: Illustrado Por Salvador Dalí, pp. 77-78)

Fun Fact: One of the earliest editions was published in 1595 by Paris: Chez A. L’Angelier.

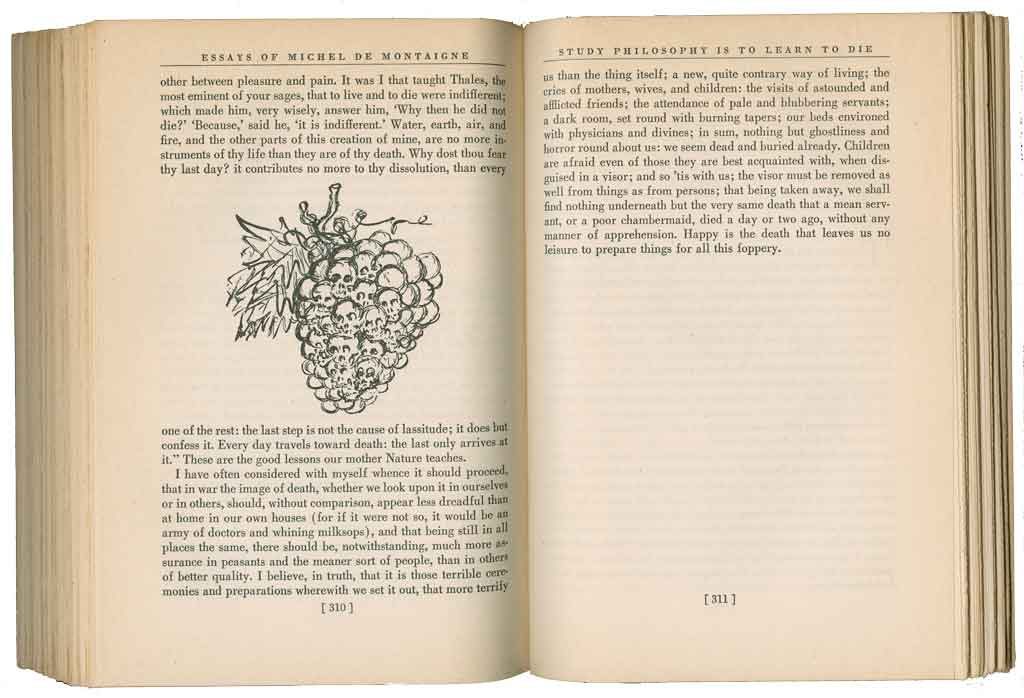

Illustrations from Essays

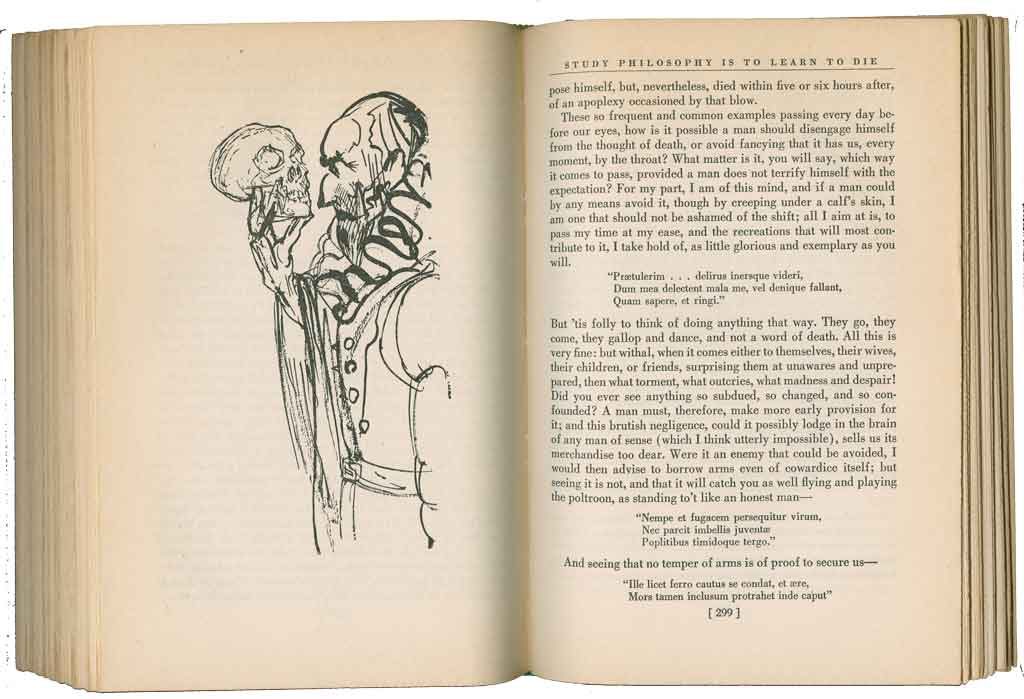

This illustration “That to Study Philosophy is to Learn to Die” is in Chapter XVII. For instance, near this particular illustration, Montaigne states, “Every day travels toward death: the last only arrives at it…” and that, “there are the good lessons our mother Nature teaches” (310). The pages before and after this illustration focus on the fact that everyone dies, and that it really shouldn’t be as scary as what everyone makes it out to be.

“Study philosophy is to learn to die”

“They go, they come, they gallop and dance, and not a word of death.”

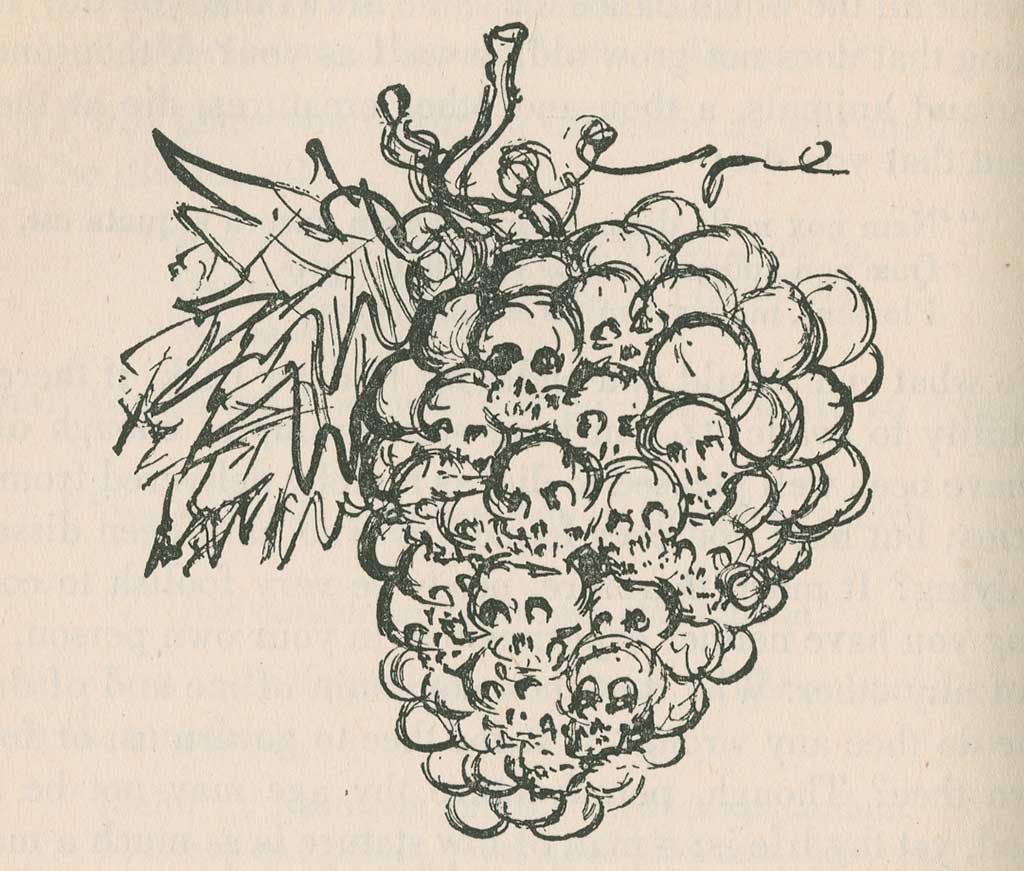

Dalí Symbol… The Skulls!

Dalí has included skulls in many of his works. Skulls can be seen as a “terrifying image of death.”

The Essays illustration shows a group of grapes, but some of the grapes are shown as skulls. A skull can also be seen in Dali’s painting, Meditation on the Harp. This skull seems to stretch out from the central figure’s arm and supported with a crutch. Other works in the museum’s collection that feature Dali’s iconic skull include Fantasies Diurnes, Untitled (Persistence of Fair Weather), Skull with Its Lyric Appendage Leaning on a Night Table Which Should Have the Exact Temperature of a Cardinal Bird’s Nest, and Atmospheric Skull Sodomizing a Grand Piano.

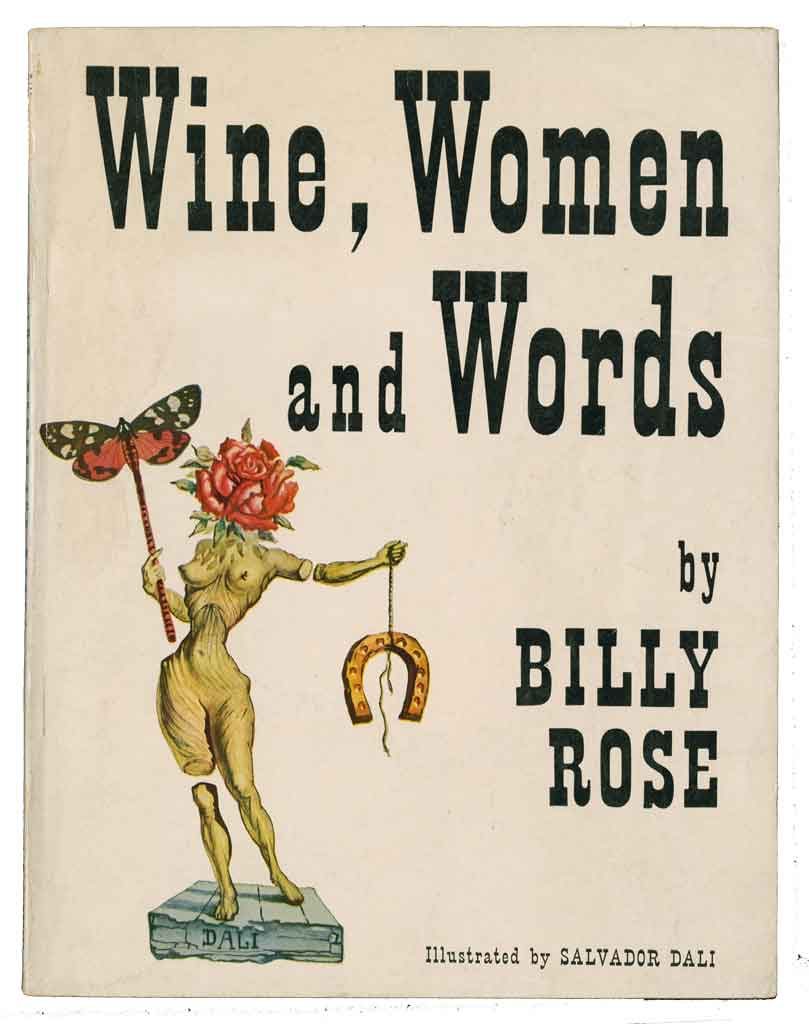

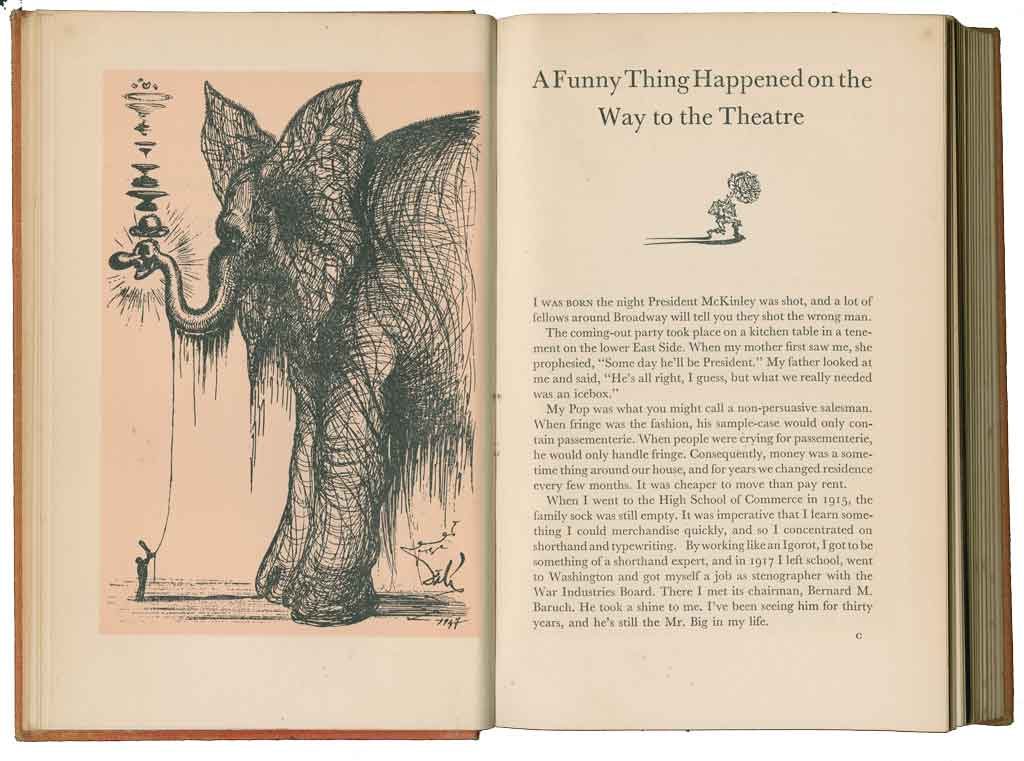

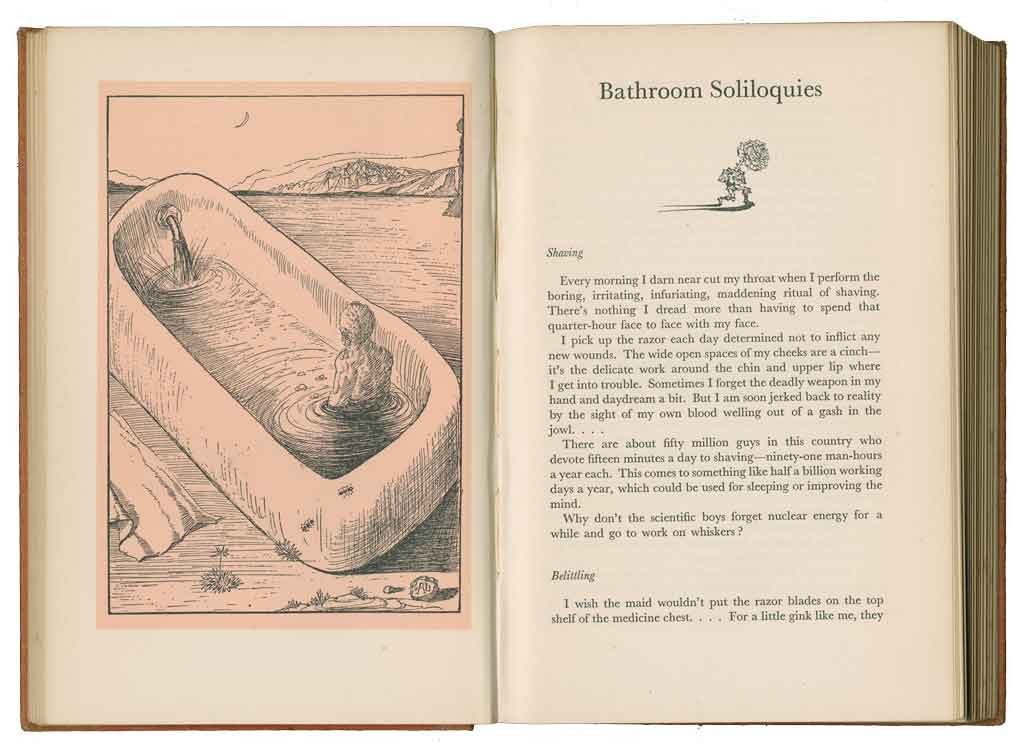

Wine, Women and Words

“This is the autobiography of the high priest of mad Broadway nights, Billy Rose, with illustrations by the high priest of Surrealist madness, Dali. In 1944, Rose had commissioned Dalí to do seven paintings to illustrate the Seven Lively Arts. They were all destroyed in a fire at the Ziegfeld Theater” (Dalí By The Book exhibition file, 1996 – Simon and Schuster, New York, 1946).

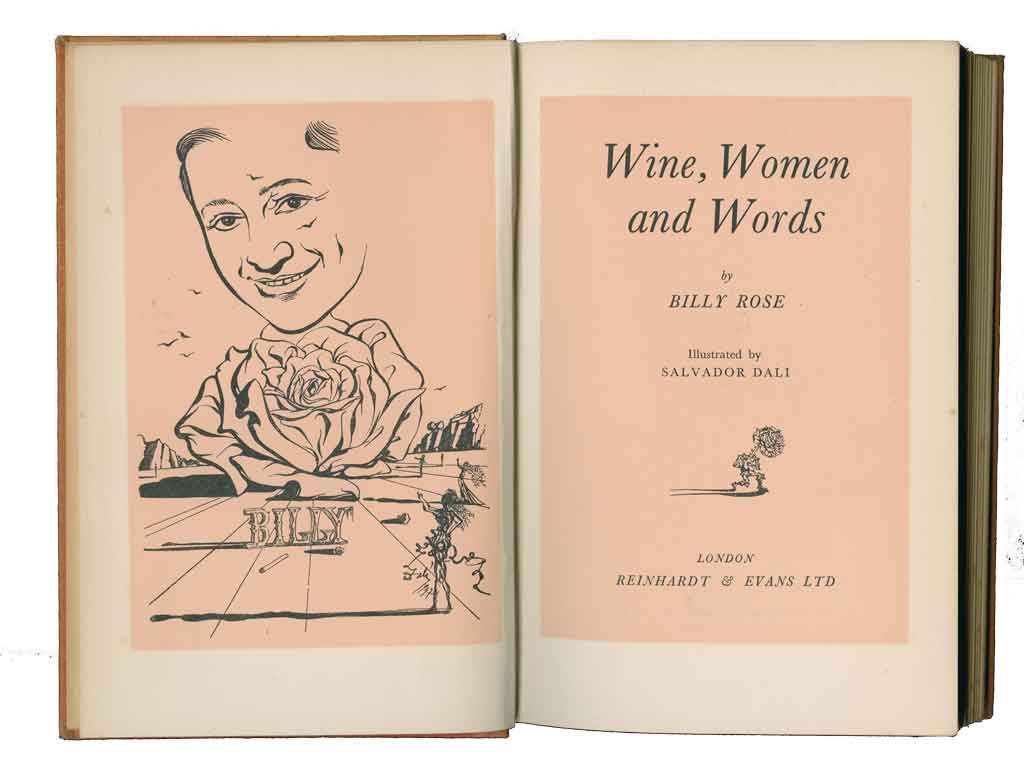

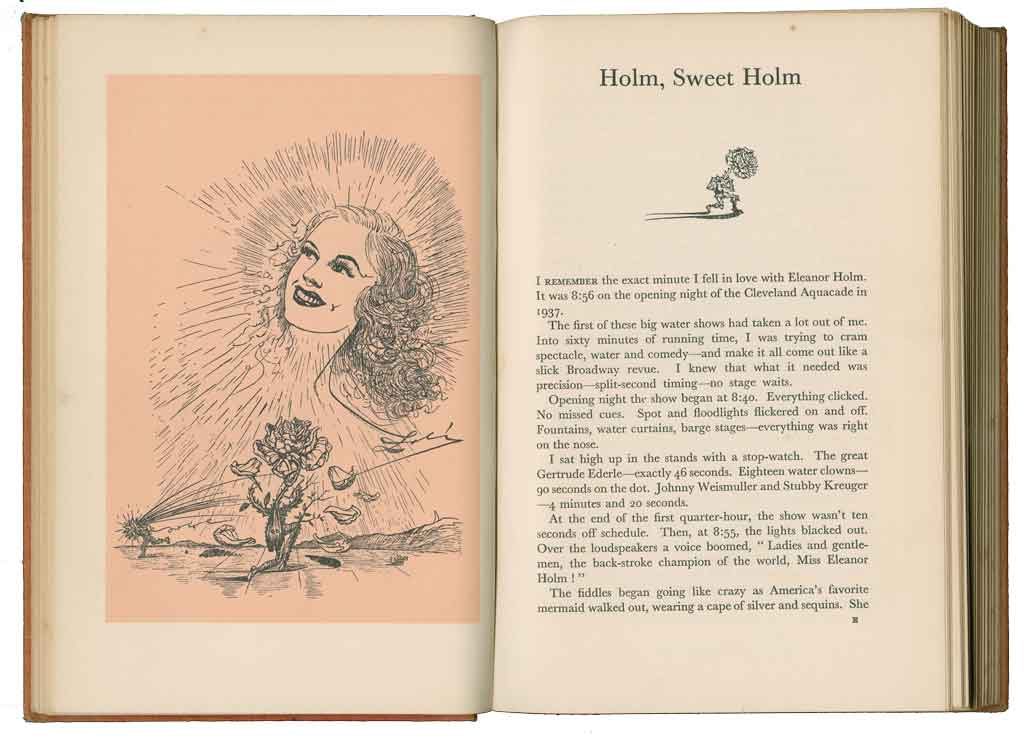

From Wine, Women and Words

The inside cover of the edition illustrated by Dali.

This illustration is shown next to the beginning of the chapter titled, “Holm, Sweet Holm.” This chapter goes into detail about how Rose met Eleanor Holm, fell in love and got married. Rose gives insight into their life together through various anecdotal stories.

Dalí Symbol…The Rose!

Roses, like the ones in the Wine, Women and Words illustrations above, can be seen in many of Dali’s works and refer to feminine beauty, transformation, and female sexuality. For example, Dali’s painting Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra has women with roses as their heads. Other works in our collection that include a rose are Memory of the Child-Woman and The Hallucinogenic Toreador. Dalí also created a window display for Bonwit-Teller’s store that included a manikin that had roses for her head, too (The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, 1976, p. 344).

“By way of demonstration, I accepted an offer to dress one of the windows of Bonwit-Teller’s shop with a surrealist display. I used a manikin whose head was made of red roses and who had fingernails of ermine fur. On a table, a telephone transformed into a lobster; hanging on a chair, my famous “aphrodisiac coat” consisting of a black dinner jacket to which were attached one beside another, so as entirely to cover it, eighty-eight liqueur glasses filled to the edge with green crème de menthe, with a dead fly and a cocktail straw in each glass” (The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, 1976, p. 344).

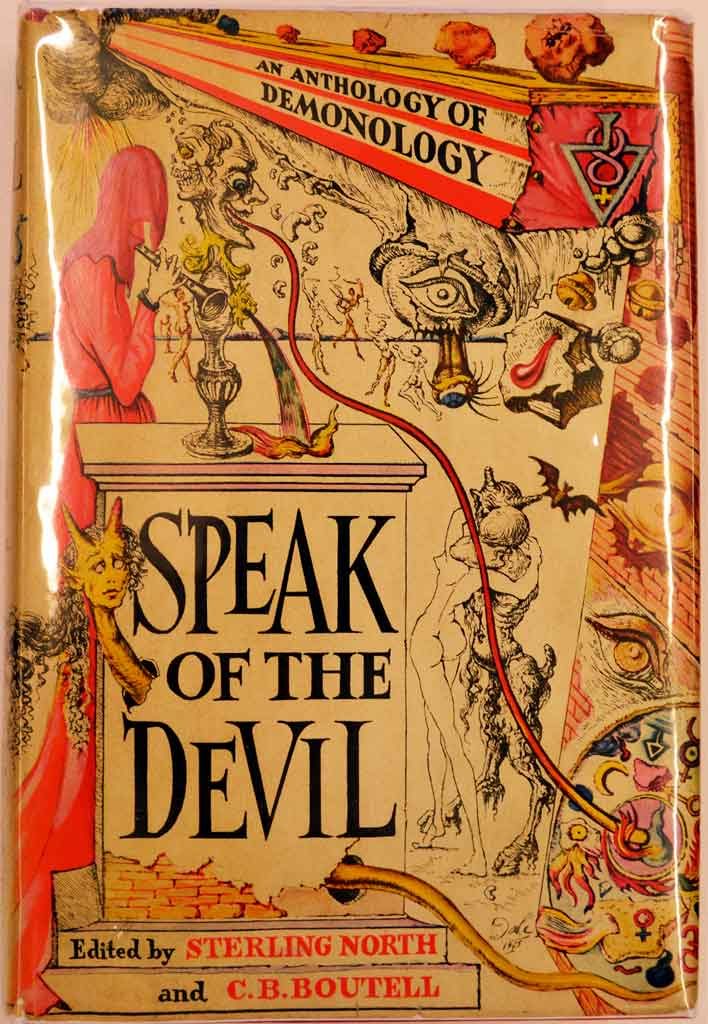

Speak of the Devil

An Anthology of Demonology

This work is a compilation of writings that focus on the devil by different authors, including Goethe, Christopher Marlowe, C.S. Lewis, Baudelaire (one of Dali’s favorite writers), Nathaniel Hawthorne.

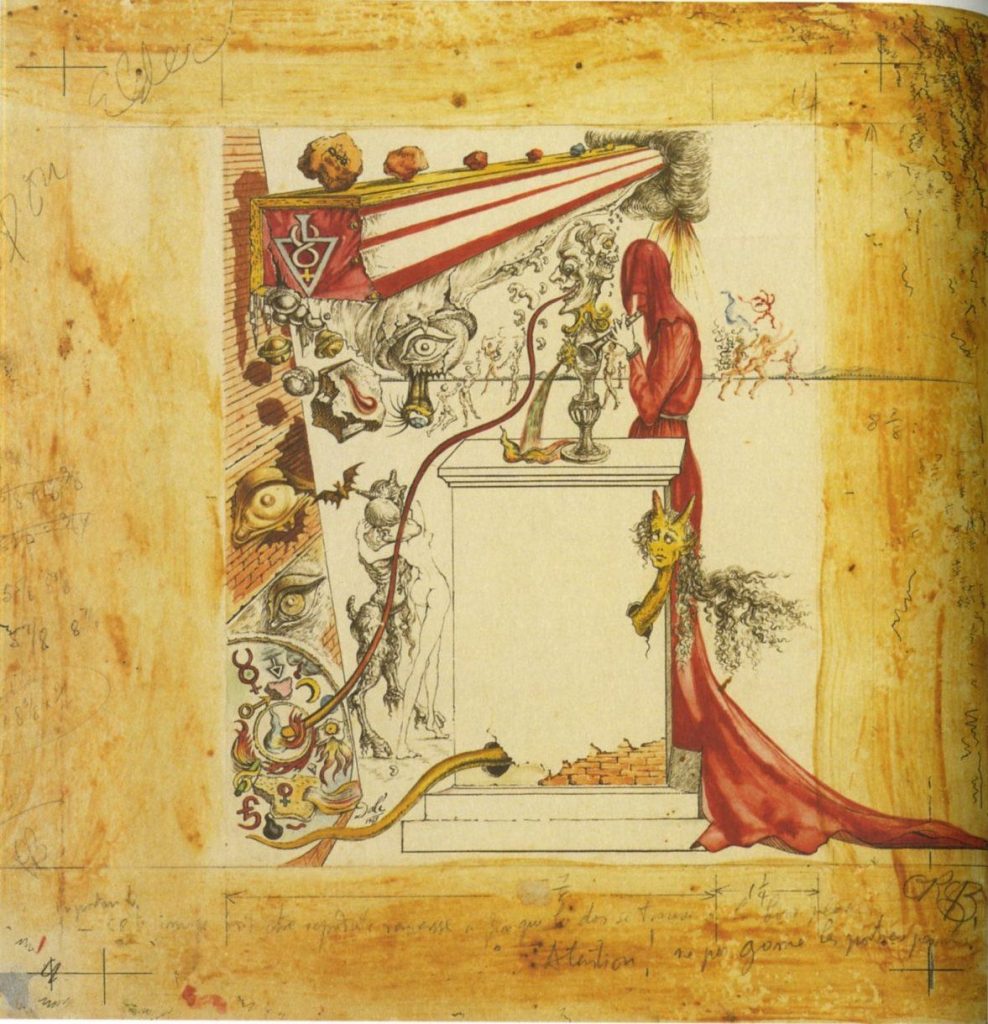

“Furthermore, Dalí doesn’t stop at doing the illustrations but also follows the publishing process very closely and provides his comments until just before the work is taken to be printed. For example, on the illustration of the dust jacket of Speak of the Devil, Dalí indicates: “[important this image must be reproduced backwards so the back is in the right place. Careful! Don’t glue over the painted parts!]”” (Dallibres).

Dalí Symbol… The Eyes!

In Dali’s work, eyes can be thought of as a way to represent “outer and inner vision.” Dalí was also very interested in Sigmund Freud’s ideas about dreams and how to understand them.

Although the artwork displayed at the Dalí Museum does not have depictions of eyes like on the cover of Speak of the Devil, eyes can be seen other works Dalí created. Dali’s work in the film Spellbound, where the depiction of eyes cannot be overlooked, is a great example.

c. 1945

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2011

Salvador Dalí’s use of eyes in his work is seen repeatedly in the film, Spellbound, in 1944. Dalí was involved in creating artwork for the set of the movie, more specifically the dream sequence. “Spellbound is premised on the idea that a repressed experience can directly trigger a neurosis. Although its approach now appears dated, it was then considered an ambitious exploration of Freudian analysis and was nominated for the ‘Best Picture’ Academy Award,” (Dalí and Film, p.176). “In a later television interview, he [Alfred Hitchcock, director of the film] explained: ‘I requested Dali. [David O.] Selznick, the producer, had the impression that I wanted Dalí for the publicity value. That wasn’t it at all. What I was after was…the vividness of dreams…[A]ll Dali’s work is very solid and very sharp, with very long perspectives and black shadows… All dreams in the movies are blurred. It isn’t true. Dalí was the best man for me to do the dreams because that is what dreams should be,’” (Dalí and Film, p. 178).

Dalí in Book Illustration Notes

Discovering Dalí in Book Illustrations, Part 1

Discovering Dalí in Book Illustrations, Part 2