From optical illusions to hidden self-portraits, there is more than meets the eye in Salvador Dalí’s artwork. Now, in a special exhibition featuring augmented reality (AR) technology The Dalí Museum offers visitors and art lovers answers to many common questions while giving a deeper understanding of the meaning behind the Museum’s collection of Masterworks.

Coined by Dalí Museum founder A. Reynolds Morse, the term “masterworks” refers to paintings exceeding five feet in height or width, painted over a period of a year or longer – in other words, they are both monumental in scale and critical Dalí paintings.

To see these works through the lens of AR:

- While viewing this page on your desktop device, use your mobile device to scan a QR code below.

- On your desktop device, click the thumbnail of the corresponding painting to view the image at full scale.

- Point your mobile device at the image and watch as Dalí’s art comes alive.

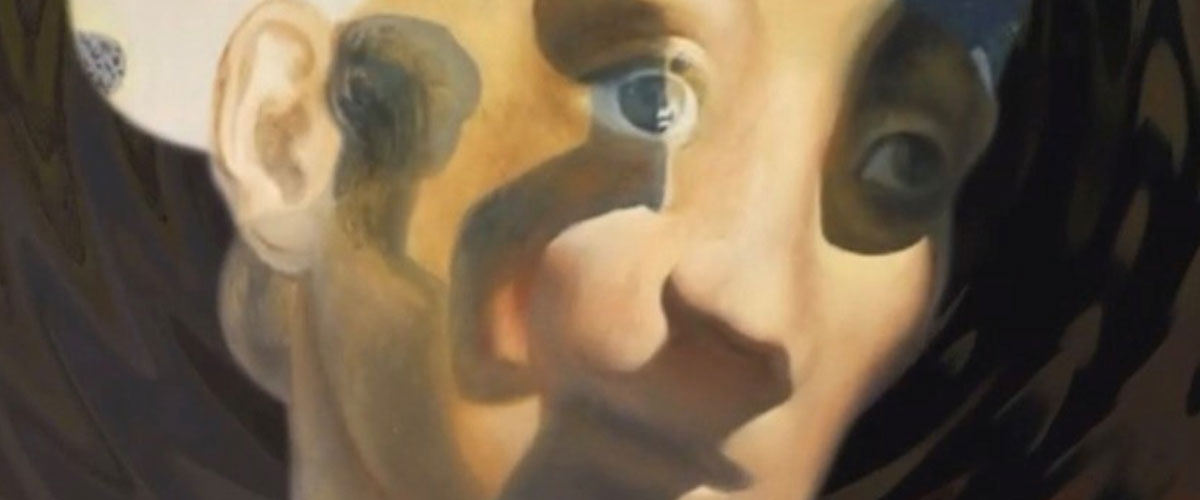

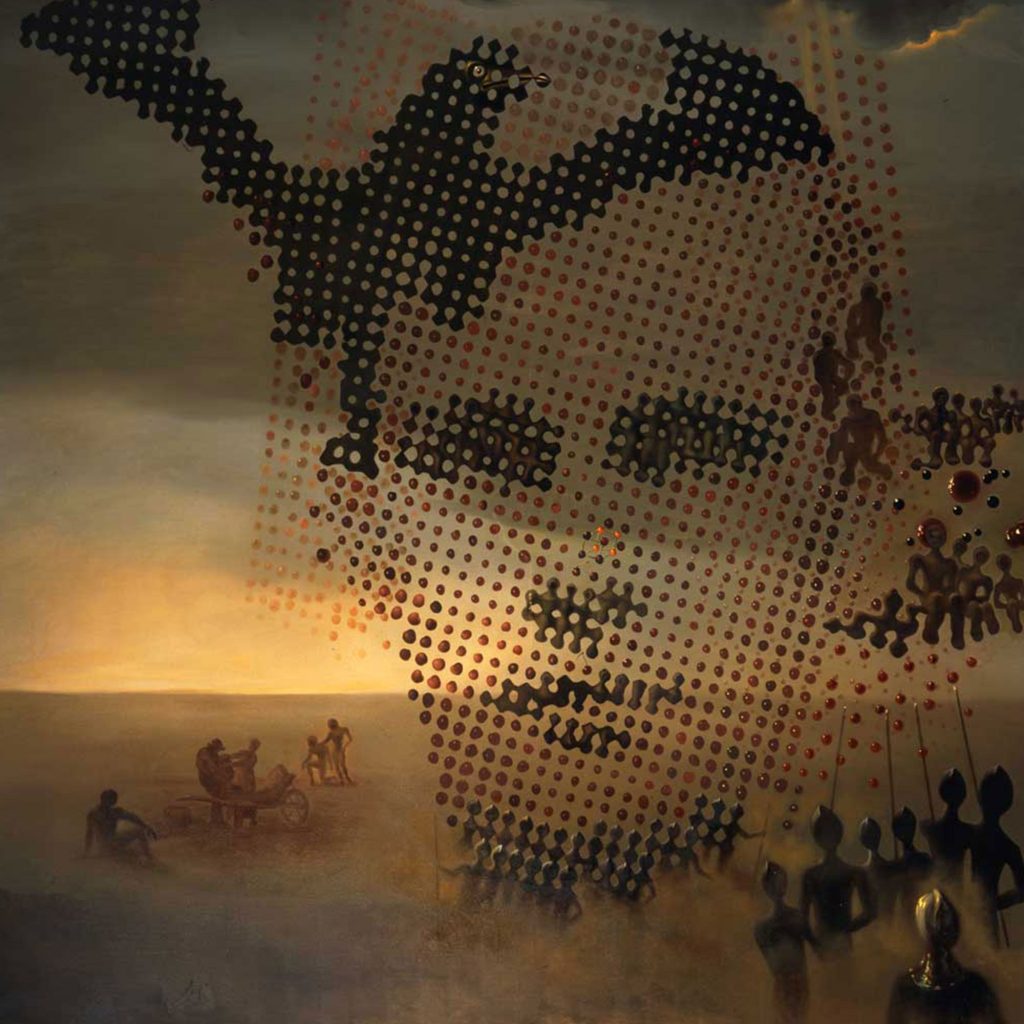

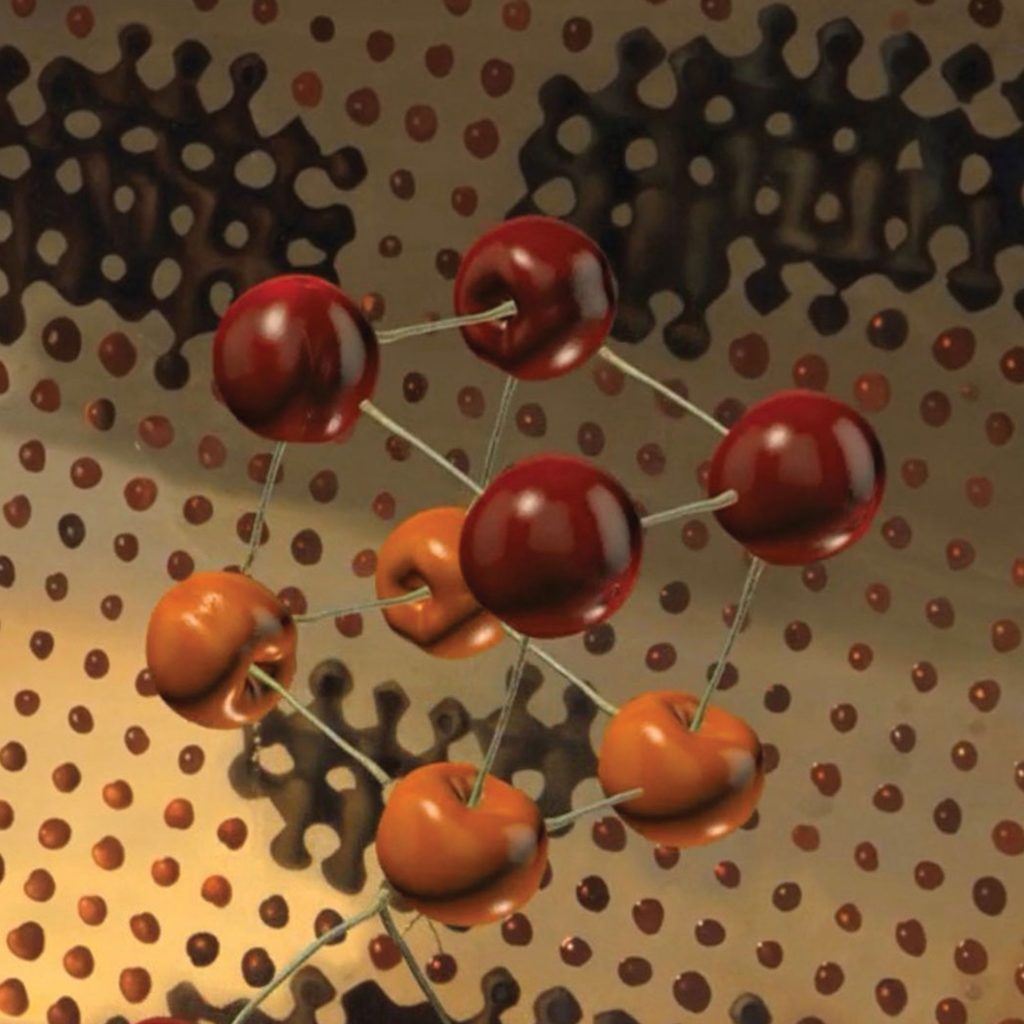

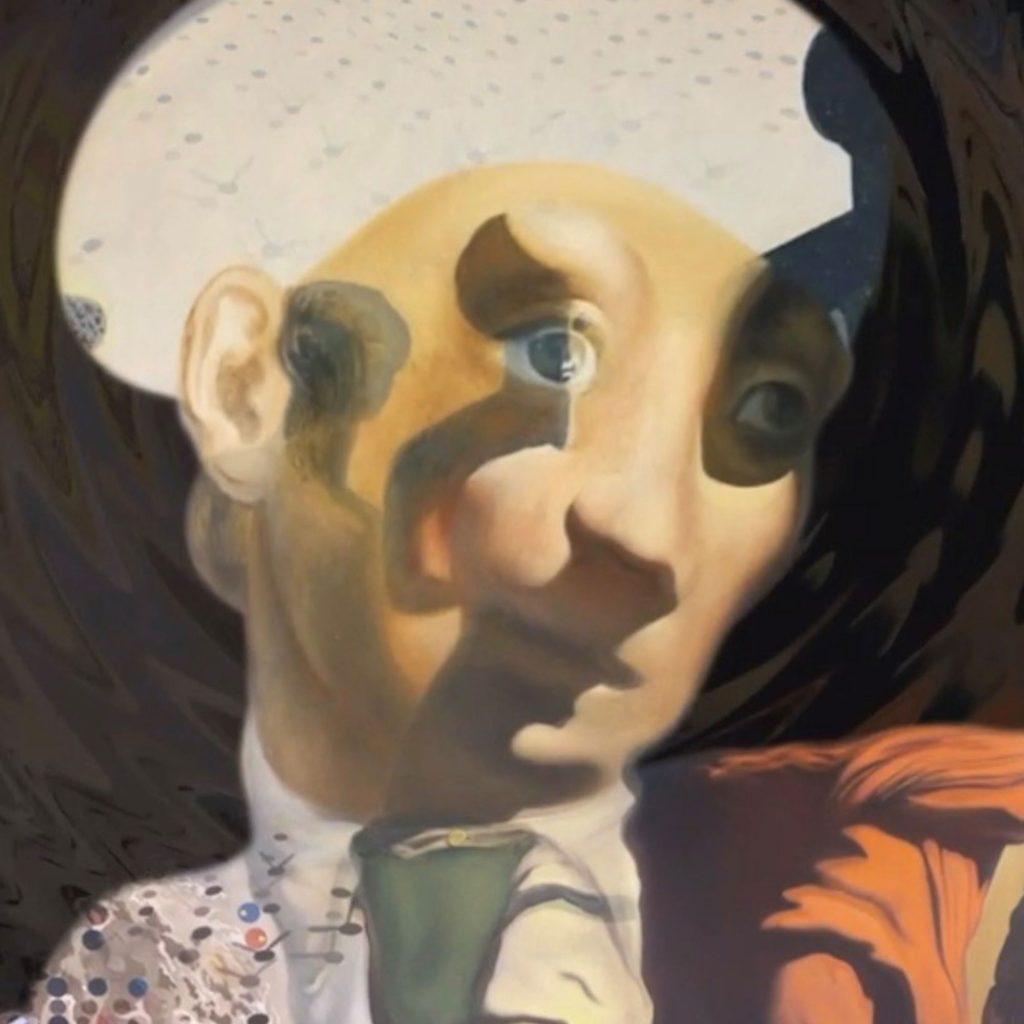

1. Portrait of My Dead Brother (1963)

This painting refers to one of the key stories in Salvador Dalí’s life, his relationship with his dead brother. While Salvador was named after his father, Salvador Dalí i Cusi, he also shared this name with his brother, Salvador Galo Anselmo Dalí, who died in 1903. Dalí felt his parents viewed him as a replacement for his dead brother, which led to the artist’s cultivation of his eccentric behavior to prove that he was different. The artist could never seem to escape the specter of a brother who shared his name and shadowed his life from birth.

At first glance, the orbs forming the image of a young man appear to be Ben-Day dots. Look closer and you will notice they are actually cherries. Together, these cherries make up the face of a young man – Dalí’s brother. In the center of the painting, just above his nose – two light cherries (representing Dalí) and two dark cherries (representing his dead brother) form a molecule, symbolizing Dalí’s identity as molecularly entwined with that of his brother’s.

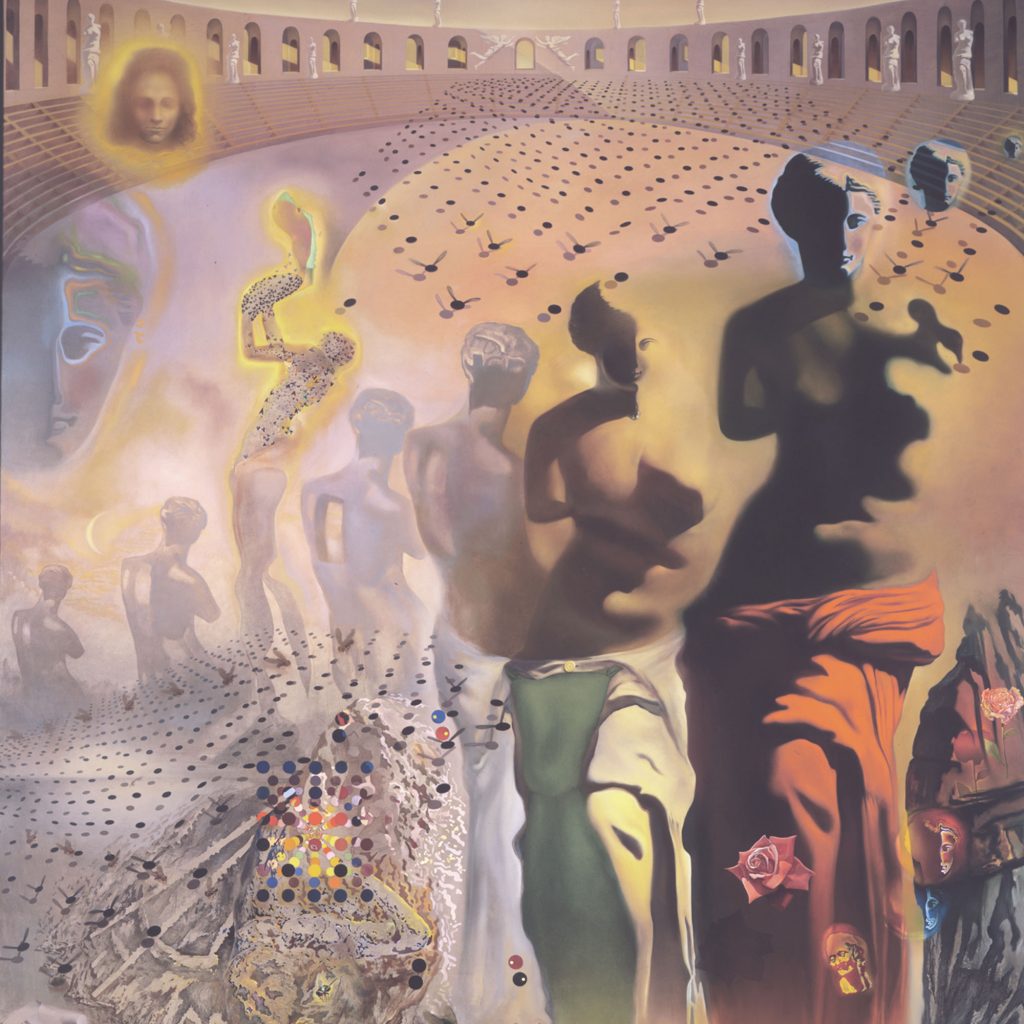

2. The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1969-70)

Dalí conceived this painting while in an art supply store in 1968. In the body of Venus, on a box of Venus pencils, he saw the face of the toreador. This double image painting repeats the image of the “Venus de Milo” several times in such a way that the shadows form the features.

Begin by examining the green skirt of Venus and you will notice it transforms into a man’s necktie and the white skirt in the background becomes his shirt. Travel up the figure and venus’ abdomen becomes his chin, her waist is his mouth, and her left breast is the nose. The pink arch forms the top of the head with the arena at the top as his hat. The tear in the eye (at the nape of Venus’ neck) is shed for the bull. The red skirt on the right Venus is his red cape.

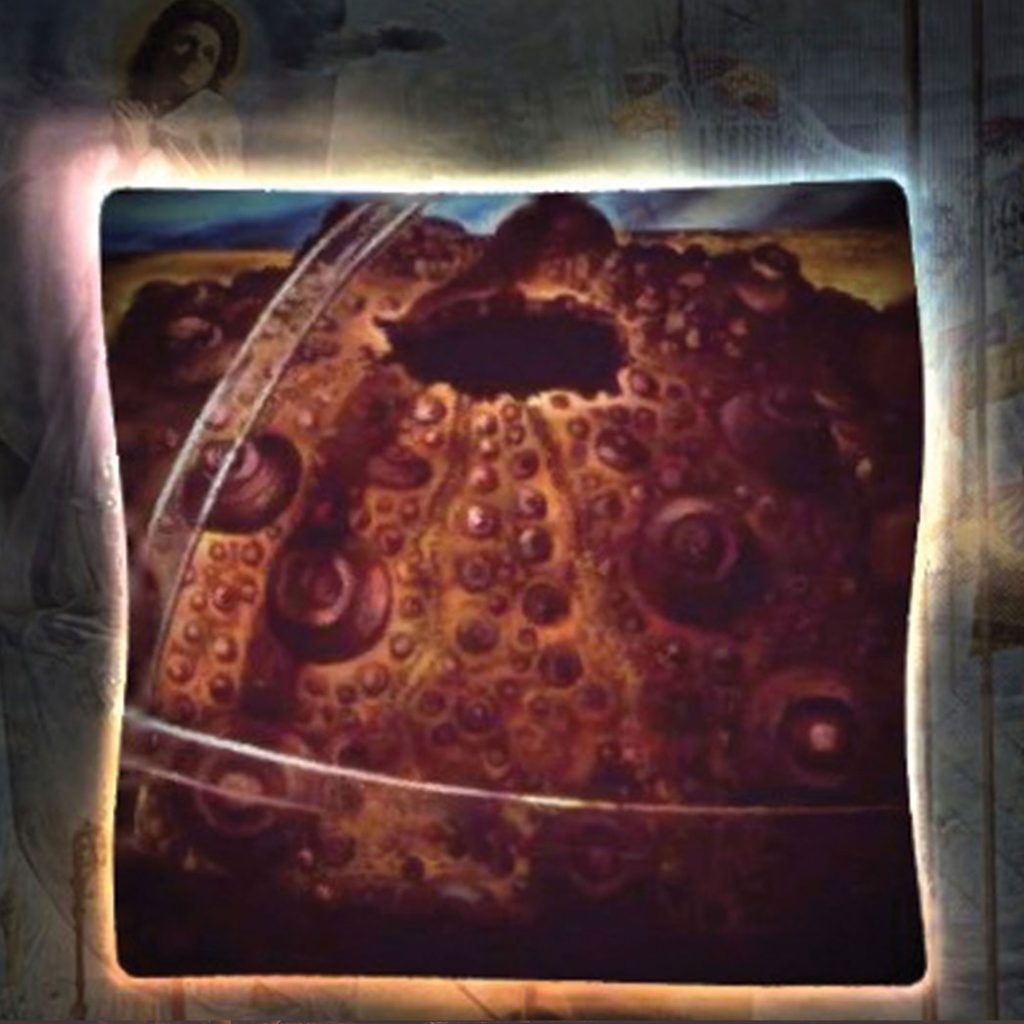

3. The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (1958-59)

This work is an ambitious homage to Dalí’s Spain. It combines Spanish history, religion, art and myth into a unified whole. It was commissioned for Huntington Hartford’s Gallery of Modern Art on Columbus Circle in New York. At thetime, some Catalan historians were claiming that Columbus was actually from Catalonia, not Italy, making the discovery all the more relevant for Dalí, who was also from this region of Spain.

Can you find the sea urchin in the middle foreground of the painting? In his book, Diccionario privado de Salvador Dalí , Dalí writes, “The sea urchin, based on the dodecahedron, is the perfect animal. It is the image of heaven.” You may wonder ‘What does a sea urchin have to do with Christopher Columbus?’. This particular type is called a “sputnik” sea urchin. And the Russian satellite of the same name, launched shortly before this work was completed. That, together with the encircling cosmic rings in the painting, hint that the sea urchin represents the age of space travel. What better connection to make in a painting celebrating the age of exploration? In fact, if you look at Columbus, he looks as though he’s just about to step upon the moon.

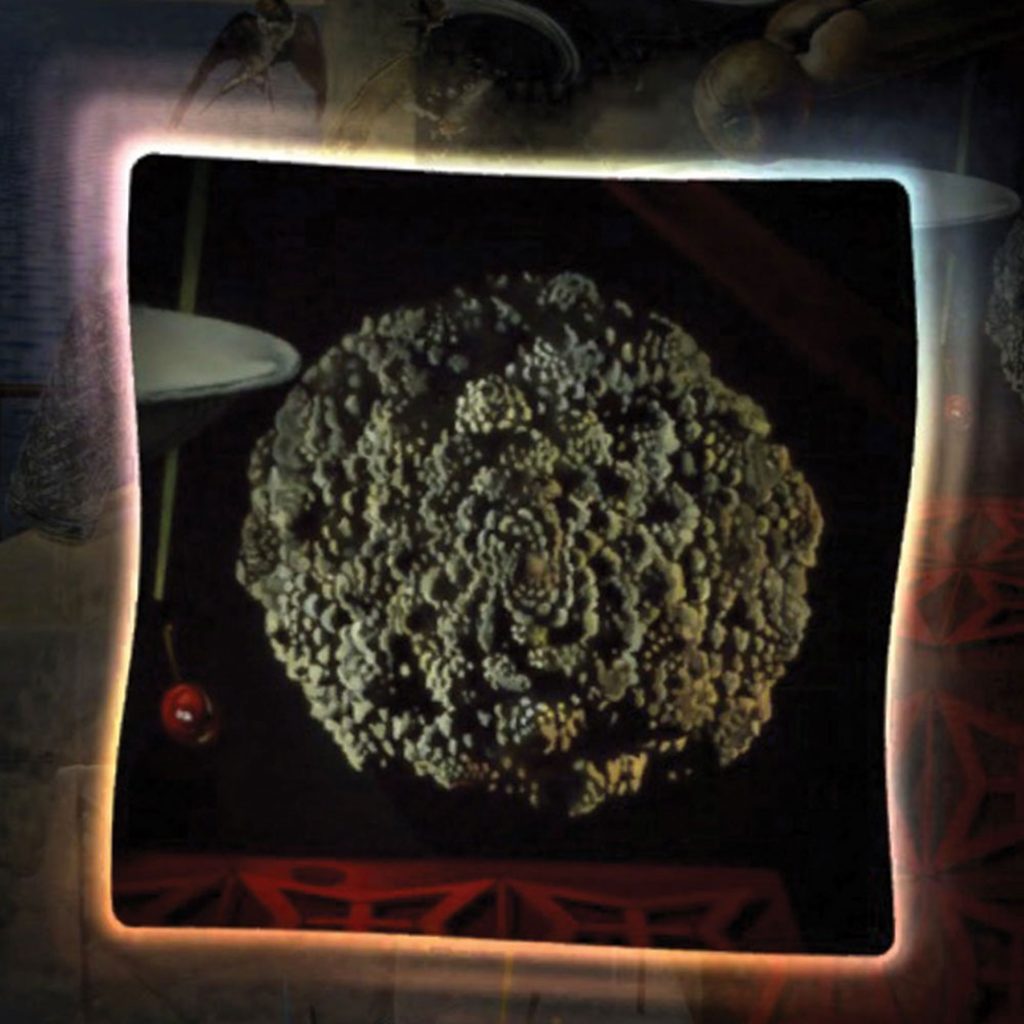

4. Nature Morte Vivante [Still Life-Fast Moving] (1956)

Emblematic of Dalí’s emerging Nuclear Mysticism, this large painting was the sixth in the series of monumental history canvases Dalí initiated in 1948, and it is the first to depart from their strictly religious subjects. While it may appear chaotic initially because of the multitude of disparate objects, for the overall composition the objects obey a greater mathematical order derived from the golden section.

In the right middle ground of the painting, you’ll find a large head of cauliflower – one of the most prominent vegetables of Dalí’s career. The vegetable exemplified some of Dalí’s favorite mathematical principles–the spirals of the cauliflower reflects mathematician Ghyka’s theory of the golden ratio as well as the Fibonacci sequence. To Dalí, the presence of math in both nature and man-made objects indicated a greater force of order in the beauty of the world. The perspective of the cauliflower draws attention to its spirals but also evokes the image of a nuclear explosion, something that was certainly weighing on minds in the 1950s. Through a cauliflower, Dalí calls attention to the logarithmic beauty of the natural world while also bringing to mind the great and devastating feats of science and math that have changed the world.

5. The Ecumenical Council (1960)

This canvas honors Pope John XXIII for trying to unite the churches through the Ecumenical Council. In the top right corner of this painting, there is yet another depiction (one of four) featuring the coronation of Pope John XXIII. But there’s something that makes this version very different from the others – it was formed using octopus tentacles. Always open to experimentation, Dalí dipped an actual octopus into paint and pressed its tentacles into the canvas. He then used the patterns and shapes left behind as the basis for yet another coronation scene. Can you make out the shapes formed here by the tentacles?

All Works: Worldwide rights ©Salvador Dalí. Fundacio Gala-Salvador Dalí (Artists Rights Society), 2020 / In the USA ©Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc. St. Petersburg, FL 2020.