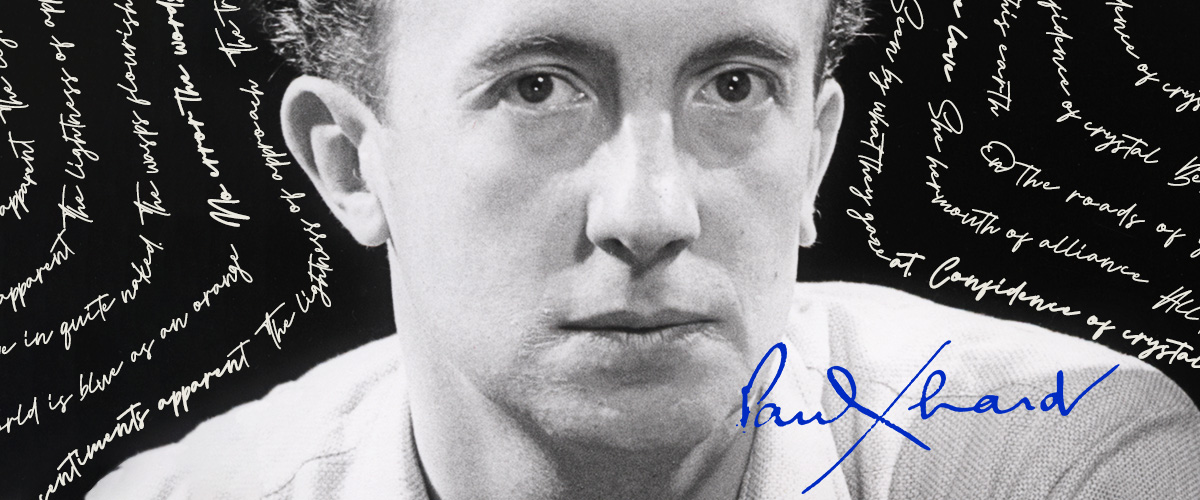

Paul éluard: Poetry, politics, love

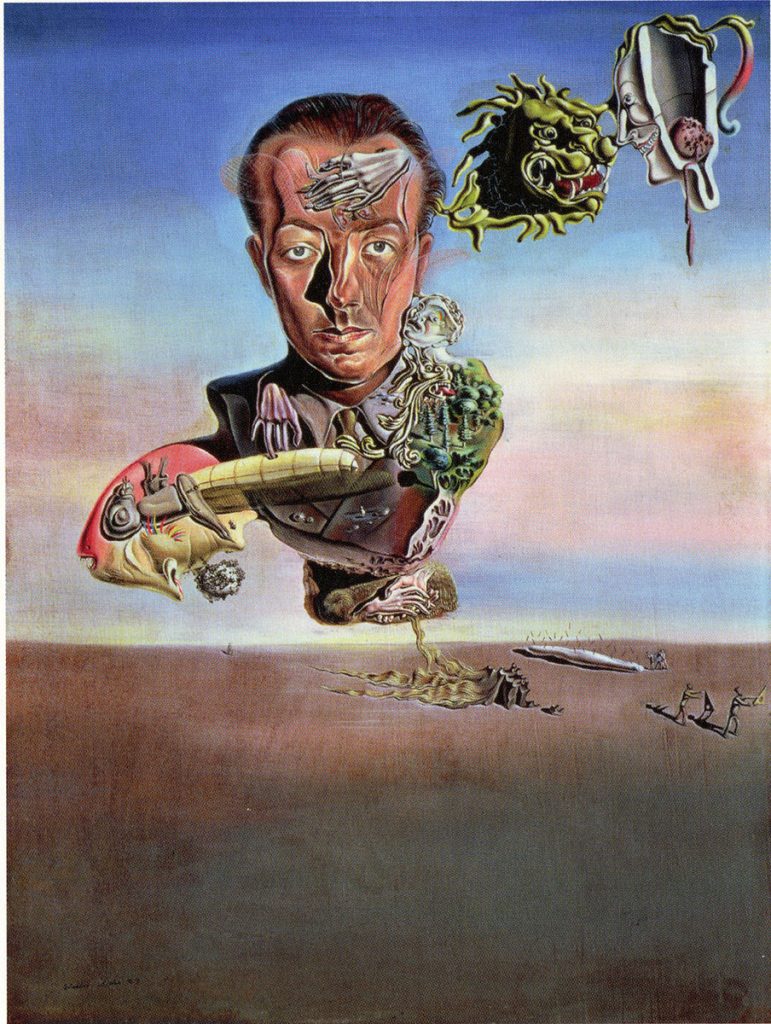

“I spoke with Éluard. I saw immediately that he was a poet of the category of Lorca – that is to say, among the greatest and most authentic.” – Salvador Dalí

This exhibition presents the story of Paul Éluard, the most celebrated and idealistic of all surrealist poets. Known as “the Poet of Freedom,” Éluard helped found Surrealism, the French art movement whose poetry celebrated dreams, love and freedom. This exhibition is curated by Peter Tush, Dalí Museum Curator of Education.

1. About paul éluard

Born Eugène Émile Paul Grindel in Saint-Denis, France, in 1895, he was an only child. Born into a lower middle class family, Éluard studied at École Supérieure de Colbert. At age 16, he contracted tuberculosis and was sent to the Clavadel sanatorium in Switzerland for two years to recuperate. There he met and fell in love with Elena Ivanovna Diakonova (Gala), sharing a love of poetry. They married in 1917 after he enlisted during World War I. In 1918, they had one daughter, Cécile.

In 1916, he chose the name Paul Éluard, borrowing the literary pen name from his maternal grandmother. He entered World War I as a medic and infantryman, but even after suffering a gas attack, he chose to work near the front lines in a military hospital. He witnessed firsthand the devastation and horror the War unleashed.

In response to the War, in 1924 Éluard helped found the surrealist movement with poets André Breton, Louis Aragon and Phillippe Soupault. While Gala would leave him for Salvador Dalí in 1929, she remained his muse long after their divorce. In the late-1930s, Éluard abandoned Surrealism to support of the French Communist Party. He became an active member of the French resistance during the Nazi occupation.

Éluard died of a heart attack in 1952, and is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France. His funeral was attended by thousands, leading French poet Robert Sabatier to write: “the whole world was mourning.”

2. éluard and surrealism

“Surrealism…is a state of mind that strives to reduce the differences between people.”

– Paul Éluard, 1936

Following World War I, Paul Éluard found himself drawn to revolutionary ideas. He crossed paths with three young French poets – André Breton, Philippe Soupault and Louis Aragon, who shared his love of the French modernist poetry and his horror of what they witnessed during the war. All became key members of the avant-garde Paris Dada Movement, then Surrealism in 1924, which Éluard helped Breton found.

Surrealism employed experimental art techniques, explored the Freudian unconscious and dreams, and was politically motivated against traditional notions of family, church and state. Éluard became one of Breton’s closest lieutenants and a key ambassador of Surrealism around Europe.

He developed a lifelong friendship with German surrealist painter Max Ernst. Together they published two collaborative books – Répétitions and Les Malheurs des immortels (“Misfortunes of the Immortals”). Their collaboration helped establish Surrealism as both a verbal and visual art movement.

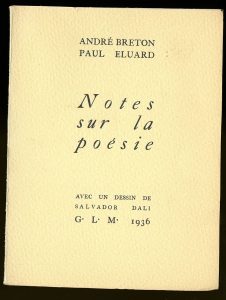

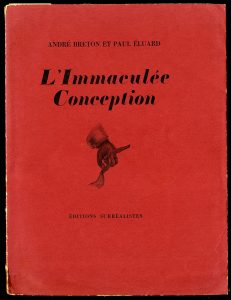

In the late 1920s, Éluard helped Surrealism find ways to engage with Communism. In 1930, he and Breton collaborated on the key surrealist work, The Immaculate Conception, and he met Salvador Dalí, whom Gala would leave him for. Despite this, Éluard remained close to Gala, and was a major friend of Dalí. An avid art collector and critic, he wrote essays about many of his friends, including Ernst, Dalí and Joan Miró, and helped organize important surrealist exhibitions.

Despite his years as a surrealist, Breton often found his poetry too conventional. By the mid-1930s, the two became estranged. Éluard severed his affiliation with Surrealism following the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition.

3. A Poet of Love – Gala

“Éluard struck me as a legendary being. He drank calmly, and appeared completely absorbed in looking at the beautiful women.”

– Salvador Dalí, on first meeting Éluard in 1929

One of Paul Éluard’s most important contributions to literature was his poetry of love and eroticism. He was charismatic, had an open marriage and was devoted to free love. Éluard championed the surrealist ideal that women were a gateway to the Marvelous, and saw love as the greatest human triumph.

Long before Salvador Dalí arrived in Paris, Éluard met Elena Ivanovna Diakonova when they were teenagers in a Swiss sanatorium for tuberculosis. They fell in love, married and had one daughter, Cécile. Éluard was responsible for giving her the nickname “Gala,” and she became his lifelong muse.

In 1917, he dedicated the following lines of his poem “One Being” to her:

A single being

Caused the pure snow to melt

Made flowers grow in the grass

And the sun is set free

Gala had other lovers with Éluard’s encouragement, but in 1930, she would leave him to become the muse, partner and eventual wife of Spanish surrealist Dalí. Despite this, Gala continued as Éluard’s muse. His ongoing obsession with Gala is documented in the posthumous publication, Letters to Gala. The frank sensuality of Éluard’s letters to Gala, written between 1924 and 1938, reveal the carnal nature of their relationship years after their separation.

4. A Poet of Love – Nusch

n.d., Presented to Tate Archive by Eileen Agar in 1989 and transferred from the photograph collection in 2012. © Tate

Paul Éluard lived in pursuit of new romances, and he had many trystes during his years with Gala. In 1930, after she left, Éluard fell in love with an Alsatian acrobat named Nusch (Maria Benz). They became inseparable and were married in 1934. Her beauty was celebrated by photographers including Man Ray, Lee Miller and Dora Maar. Éluard collaborated with Man Ray to publish Facile, a collection of erotic poetry woven around Man Ray’s nude photos of Nusch. The 1932 poem “In a New Night” provides some of the flavor of his Nusch-inspired work:

Woman with whom I have lived,

Woman with whom I live,

Woman with whom I shall live;

The same woman always,

You must have a red cloak,

Red gloves, a red mask,

And black stockings;

Reasons, proofs

For seeing you quite naked;

Unsullied nakedness, O adorning dress!

Breasts, O my heart!

Nusch became part of Éluard’s surrealist social circle, collaborating on surrealist drawing games and making photomontages. She formed close bonds with key surrealist muses including Leonora Carrington, Lee Miller and Ady Fidelin. She frequently wore Elsa Schiaparelli designs influenced by Surrealism.

At the end of the decade, Éluard formed a close friendship with Picasso. He encouraged Nusch and Picasso to sleep together, feeling it was the highest compliment he could pay to the great artist. Picasso celebrated her beauty in a series of portraits at the end of the 1930s.

During World War II, Nusch and Éluard worked for the French Resistance. Following the liberation, Nusch died from a massive stroke at age 40. Devastated, Éluard could only move forward by focusing on the Communist Party.

5. Éluard and communism

In 1927, Paul Éluard became committed to Communism’s fight for the oppressed and he sought common ground between Surrealism and the French Communist Party. Soon the surrealists were estranged from the Party, but Éluard returned to Communism during the Spanish Civil War to denounce Fascism. Responding to Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica, he wrote the poem “La Victoire de Guernica” (“Victory of Guernica”) and the two artists became inseparable.

During the Nazi occupation of France during World War II, Éluard became a vital member of the Resistance. Several of his poems – “Poésie et vérité” (1942; “Poetry and Truth”), “Au rendez-vous allemand” (1944; “To the German Rendezvous”), and “Dignes de vivre” (1944; “Worthy of Living”) – secretly circulated during the war and served to strengthen morale.

“Liberté, j’écris ton nom” (“Liberty, I Write your Name”), written in 1942, was a message of hope and freedom. It is one of the most important poems in modern French history. Following the Liberation, Éluard was hailed as one of the great poets of the Resistance.

Tragically, Éluard’s wife Nusch died shortly after the war, and he became inconsolable. He was only able to move forward by putting his work in the service of Communism as a diplomat. In 1949, he met Dominique Laure at the Congress of Peace in Mexico. They married, but their relationship was brief. In 1952, Éluard died of a heart attack at age 57. His funeral was organized by the French Communist Party. It was attended by thousands who spontaneously gathered in the streets.

“Liberty, I Write your Name” excerpt

Translated by George Dillon and William Jay Smith

On my notebooks from school

On my desk and the trees

On the sand on the snow

I write your name

On every page read

On all the white sheets

Stone blood paper or ash

I write your name

On the golden images

On the soldier’s weapons

On the crowns of kings

I write your name

On passionless absence

On naked solitude

On the marches of death

I write your name

On health that’s regained

On danger that’s past

On hope without memories

I write your name

By the power of the word

I regain my life

I was born to know you

And to name you

Liberty.

“The Victory at Guernica,” 1937

Translated by Noelle Gillmor

Lovely world of hovel

Pit and field

Faces fit for fire faces fit for cold

For denial or for night for curses or for blows

Faces fit for anything

You are watched by the gaping void

Your death will serve as warning

Death heart turned upside down

For earth sky water sleep

For the very misery

Of your life

They claimed to seek good fellowship

They rationed the strong sentenced the mad

Doled out alms split pennies in half

They smothered each other with civilities

They are persistent far too insistent they are not of our world

Women children have that same bounty

Of spring’s green leaves and pure milk

And endurance

In the purity of their eyes

Women children have that same bounty

In their eyes

Men defend it as best they can

Women children have those same red roses

In their eyes

They all display their blood

Fear and courage to live and die

Death so hard and yet so simple

Men for whom such bounty was sung

Men for whom it was flung to ruin

True men in whom despair

Feeds the greedy fires of hope

Together let us unfold the latest bud of the future

Pariahs death earth and the villainy

Of our foes all wear the humdrum

Tones of our night

We will force them to give way

6. Éluard the Poet

1930

Collection of The Dalí Museum

Library & Archives

As a writer, Éluard’s goal was to break with conventional literature in order to revitalize language as a subversive force. He published over seventy books of poetry and essays dedicated to his two main themes – the rejection of tyranny and the search for love. Influenced by modernist French writers like Guillaume Apollinaire and Arthur Rimbaud, his poetry often avoided punctuation, believing that rhythm created natural punctuation. Compared to the violent imagery of his colleagues, his poetry was low-key, everyday and lyrical. He saw poetry as capable of arousing an awareness of the struggle for political, social and sexual liberation.

Over a two-week period in 1930, André Breton and Paul Éluard collaboratively wrote one of the most important surrealist works, The Immaculate Conception. Its automatic text traces the life of man from Conception and Intra-Uterine Life to Death and The Original Judgement. The central section, the “Possessions,” is a celebrated series of “simulations” of mental instability. The goal was to demonstrate the close connections between the language of madness and poetry. Below is an excerpt from “Simulation of Delirium of Interpretation,” which overlaps with Salvador Dalí’s development of the Paranoiac-Critical Method. The subject feels like a bird and interprets everything in relation to this:

“Simulation of Delirium of Interpretation”

“The shower’s dazzling colors speak parrot language. They hatch the wind that emerges from its shell with seeds in its eyes. The sun’s double eyelid rises and falls on life. The birds’ feet on the windowpane of the sky are what I used to call the stars.”

“Feather summer is not yet over. The trapdoors have been opened, and the harvest of down is being thrust inside. The weather is molting.”

“The phoenixes come, bringing me my ration of glowworms, and their wings which they constantly dip in the gold of the earth are the sea and the sky which glow only on stormy days and which hide their lightning-tufted heads in their feathers when they fall asleep on the air’s one foot.”

(Translated by John Ashbery)