Dalí’s EMPORDà: EXPLORING THE LANDSCAPE

Curated by Kelsey Hallbeck

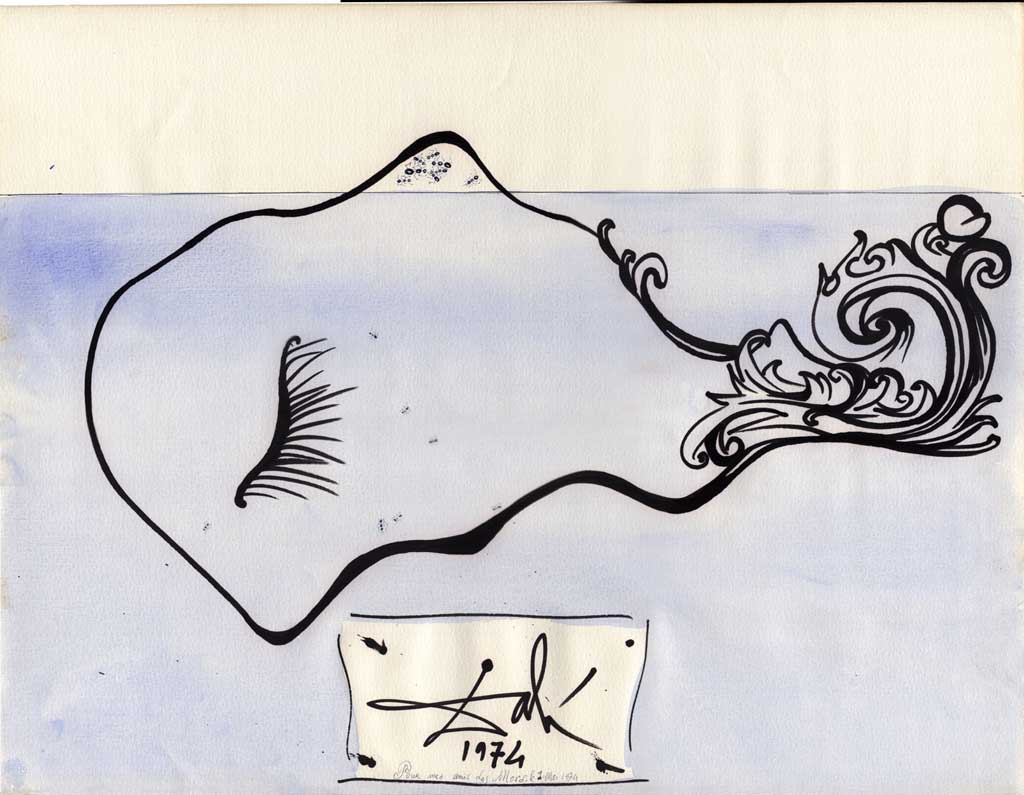

Dalí’s Empordà: Exploring the Landscape, examines Dalí’s strong sense of place attached to his homeland of Catalonia, Spain. “Sense of place” is defined by Oxford as, “an umbrella concept that includes all the other concepts—attachment to place, national identity, and regional awareness.” This online exhibition will focus on important Dalí locations, covering two apartments in Figueres, his family’s summer home in Cadaqués, and his expansive residence in Port Lligat. To quote one of the Museum’s benefactors, A. Reynolds Morse: “…even a cursory knowledge of Dalí’s ‘Romantic Ampurdan’ is of enormous value in reassessing the painter’s work.” The Morses took their first trip to Dalí’s homeland in 1954, and the following photos from our archive that comprise this online exhibition were more than likely taken by the Morses, with a few exceptions, anywhere between their first trip and 1983.

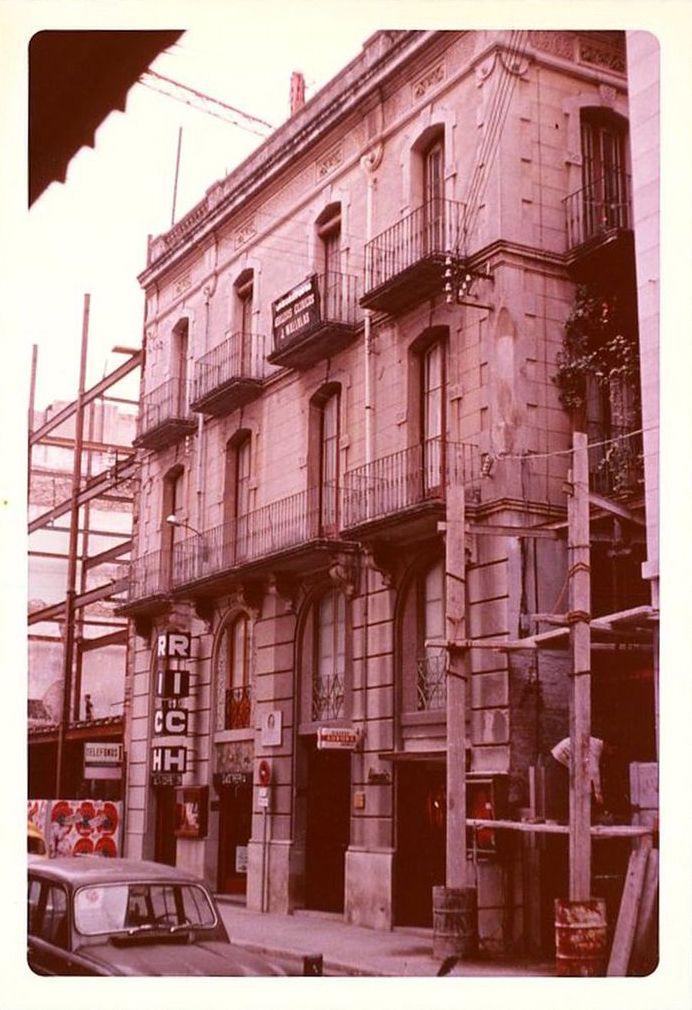

20 Carrer Monturiol, Figueres, Spain

“Figueres, the artist’s birthplace, shaped the microcosm of his childhood and youth, provided him with landscapes, friendships and experiences that he would distill by means of his own creative filters” (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, p.35).

“A good place to begin such a pictorial narration is in Figueres, Spain” (The Dalí Adventure, p.206). Salvador Dalí was born on May 11, 1904 at 20 Carrer Monturiol, which is now known as 6 Carrer Monturiol (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, p.35). Dalí, his father, Salvador Dalí Cusí and his mother, Felipa Doménech Ferrés lived alone until the birth of his sister, Anna Maria on Jan. 6, 1908. Shortly after, Dalí’s grandmother, Maria Anna Ferrés, and his Aunt Caterina, moved into the apartment above theirs but could often be found downstairs in the Dalí’s apartment.

The family lived on the first floor of the apartment, connected by an internal staircase to his father’s notary office on the ground floor. The apartment’s greatest feature, however, was not located within the interior. Instead, the greatest feature was located on the exterior – a large terrace that ran the full length of the side of the building, which overlooked a garden full of chestnut trees that were a part of the home of the Marchioness de la Torre, a local aristocrat. From the terrace, Dalí could see the Empordà plain, with the mountains of the coastal range of Sant Pere de Roda at its edge, in addition to the garden (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.23).This seemingly limitless plain would make an appearance in his paintings, along with other elements of the landscape.

This terrace, while a seemingly small detail, not only provided a great view but was also the heart of the Dalí home. Despite being four when the family moved in 1912, Anna Maria recalled this terrace later in life with deep nostalgia. The terrace was embellished with pots of lilies and sweet-smelling spikenard (spikenard would always be Salvador’s favorite flower as a result), and his mother kept an aviary at one end where she bred canaries and doves (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.23). Anna Maria remembered the canaries fondly and Dalí did not, only briefly mentioning “a warble of canaries” on the first page of his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. He also depicted a canary in his painting The Sick Child, but it is unknown if this is a reference to his mother’s birds or a metaphor for feeling caged.

Also recalled by Anna Maria was the terrace’s dual purpose. Not only was it a makeshift aviary and garden, but it also served as Dalí’s first studio where he completed his first drawings. Similar to scratchboard, Dalí would create tiny swans and ducks by scratching the red paint off the tabletop to reveal the white surface underneath. His mother’s delight with his efforts was apparent, and happily expressed with the following phrase: “When he says he’ll draw a swan, he draws a swan; and when he says he’ll do a duck, it’s a duck” (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.25).

Dalí himself did not have much to say about this residence, only noting in The Secret Life of Dalí his jealousy of Narcís Monturiol, an engineer, artist and writer most notably remembered as the inventor of the first successful underwater submarine. Due to his accomplishments, Monturiol had both a statue built in his honor and a street named after him, coincidentally, the one Dalí resided on. He even fails to mention the move from this apartment to the next in The Secret Life, where Dalí writes as if for the first twenty-five years of his existence he lived in the new apartment (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.40). Although it seems as if Dali would have rather not acknowledged his first home, today, Dalí’s birthplace is identified by a plaque adhered to the façade of the building.

In 1912, the aforementioned move was executed and the family moved just a bit farther East on Monturiol Street to the upper floor of number 24, a new building designed by the same architect where Dalí would predominantly spend the remainder of his childhood. This new apartment space had two utility rooms that were former laundry rooms, one of which Dalí converted into a studio (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, p.36). Besides this feature, the new terrace, located on the roof, provided a panorama of the Bay of Roses. For the duration of his childhood, he was consistently bounced at periodic points of the year between this location and the following.

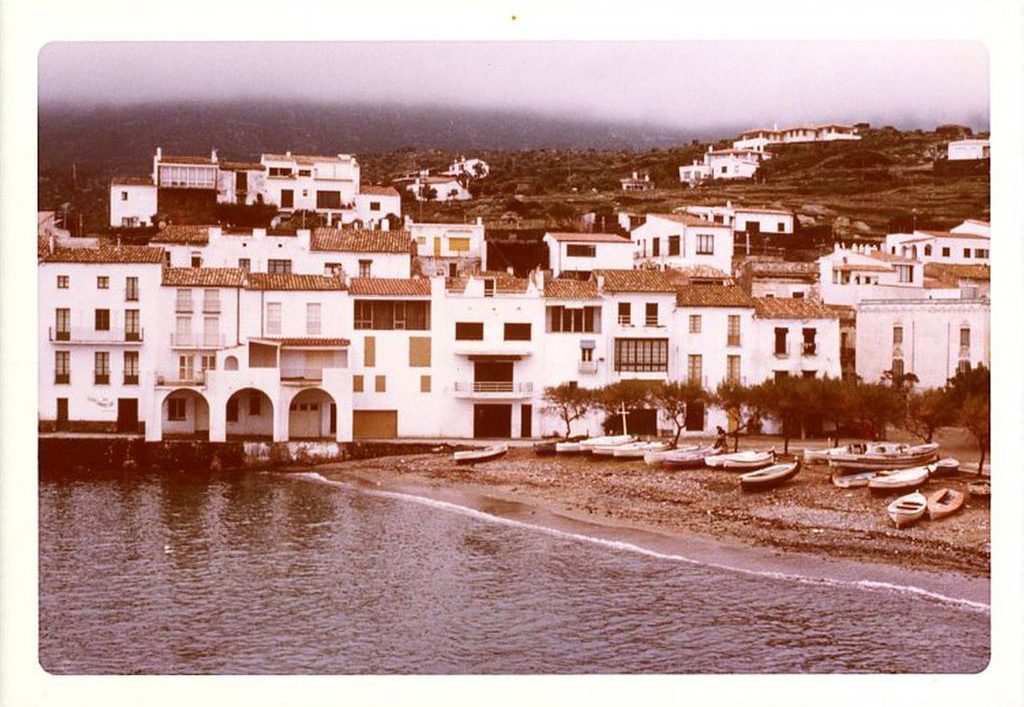

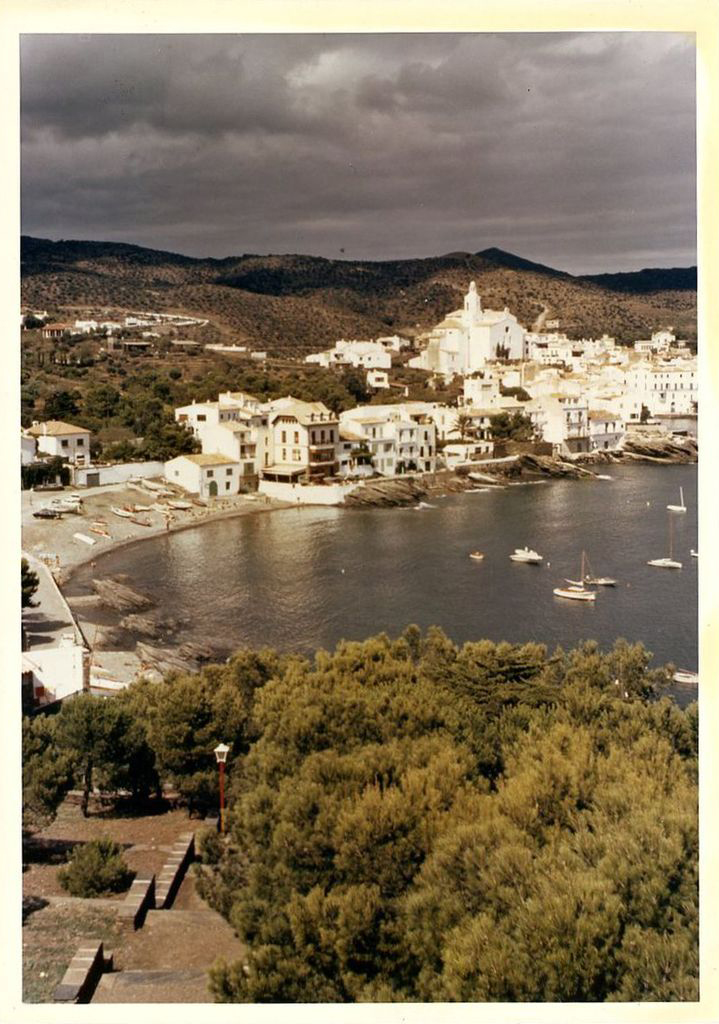

Es Llané, Cadaqués

“My summers were wholly taken up with my body, myself and the landscape, and it was the landscape that I liked best. I, who know you so well, Salvador, know that you could not love the landscape of Cadaqués so much if in reality it was not the most beautiful landscape in the world – for it is the most beautiful landscape in the world, isn’t it?” –Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí p.127

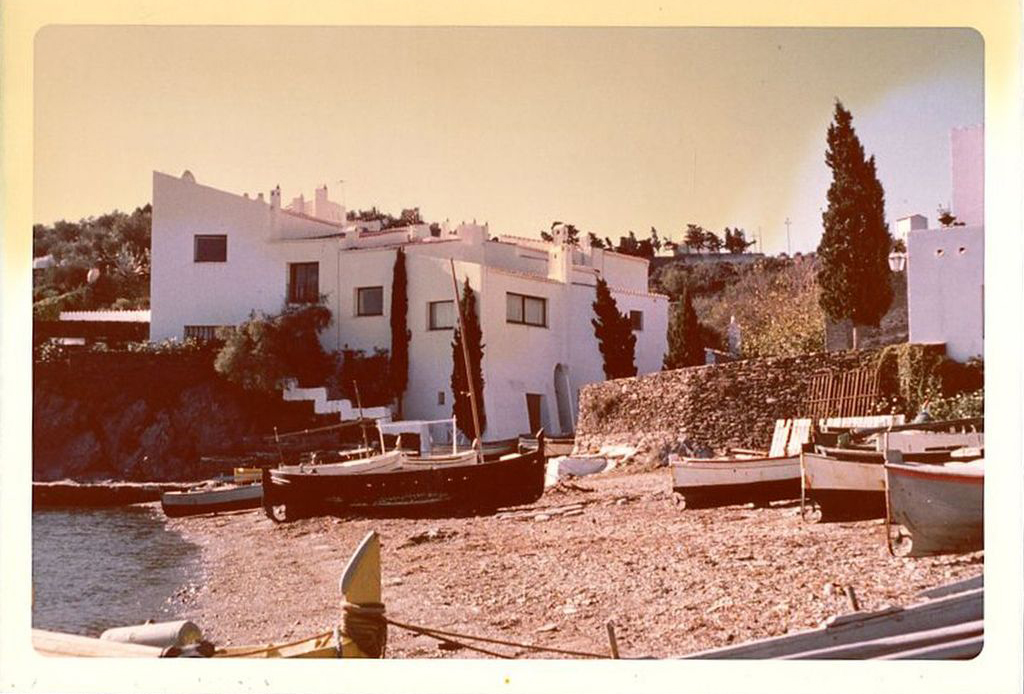

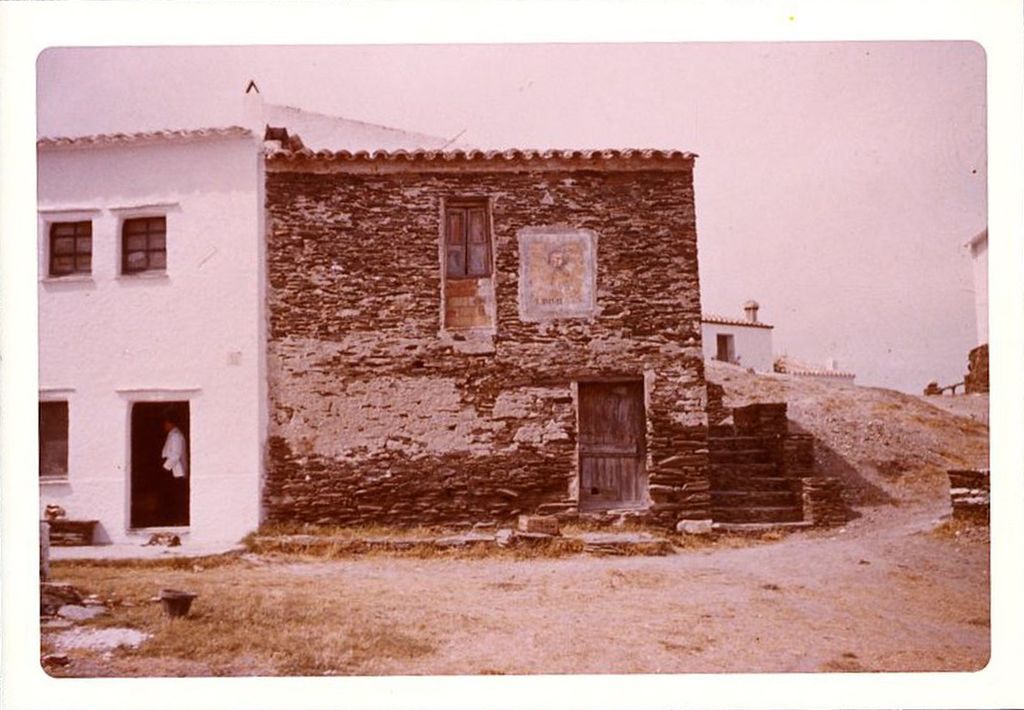

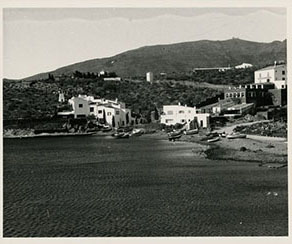

The Dalí family began to spend summers in Cadaqués in 1908. Pepito Pichot, a good friend of Dalí’s father, inspired him to return to Cadaqués (Dalí Sr. was originally from Cadaqués) after his own family successfully established a home there that could accommodate their large family. After many visits to the Pichots at their home in Es Sortell, Dalí’s father caved and and admitted to wanting to rent or own property there (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, 35). Upon hearing this, Pepito arranged for the Dalís to rent a converted stable from his sister, Maria, on Es Llané beach. Pictured on the left.

Despite its ideal location and ease of acquirement, the home lacked a studio fit for Dalí. Dalí’s father solved this problem by renting a small space for him at Punta d’en Pampà, beside Port Alguer (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, 98). The space wasn’t much, described as run-down even, but it sufficed. “From the balcony the sea and the sky could be seen, and Dalí was able to admire the boats arriving with their sun-yellowed sails open to the wind. Here he spent full afternoons painting until it would get dark and the stars shone out” (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, p.98), illustrated by his painting Self-Portrait (Cadaqués).

He wrote to his uncle, Anselm Domènech in 1920 about his time in Cadaqués. “I spent a delicious summer, as always, in the ideal and dreamy village of Cadaqués. There, beside the Latin sea, I gorged myself on light and color. I spent the fiery days of summer painting frenetically and trying to capture the incomparable beauty of the sea and of the sun-drenched beach. I’m growing more and more aware all the time of the difficulty of art; but I’m also growing to enjoy it and love it increasingly” (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.65).

It was in Cadaqués that Dalí found all the artistic inspiration that he would ever need. So much so that he described himself as “a human incarnation of his primitive landscape” (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí p.36). Due to only visiting in the summers, he often felt impatient throughout the school year for summer to arrive so that he could return. As he grew up, he invited friends to their summer home, and among these friends was Federico García Lorca, who Dalí met at University and went on to become a very loved poet and playwright. He first visited the Dalí family here in 1925 and again in 1927. These peaceful, routine summers in Cadaqués and visits from friends were about to come to an end for a couple of reasons. The first would be the arrival of Gala, Dalí’s future wife, who arrived in Cadaqués in August of 1929 with her then-husband, Paul Éluard and their daughter Cécile.

“…in the conservative Empordà, to go out with a Frenchwoman was considered tantamount to frequenting a prostitute. This particular Frenchwoman, to make matters worse, was married as well as sexy and shameless and the village tongues were soon wagging (they would wag even more when they discovered she was in fact Russian)” (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.229). Dalí’s father, always one to avoid gossip whenever possible due to his job as a notary, immediately changed his will on Sept. 26, 1929 because of Dalí’s relationship with her. The entire Dalí estate, including the Cadaqués home, now went to his sister and not equally to both children. Spanish law did not allow for the complete write off of children, forcing his father to award the absolute minimum of 15,000 pesetas (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.230). He was as good as disinherited.

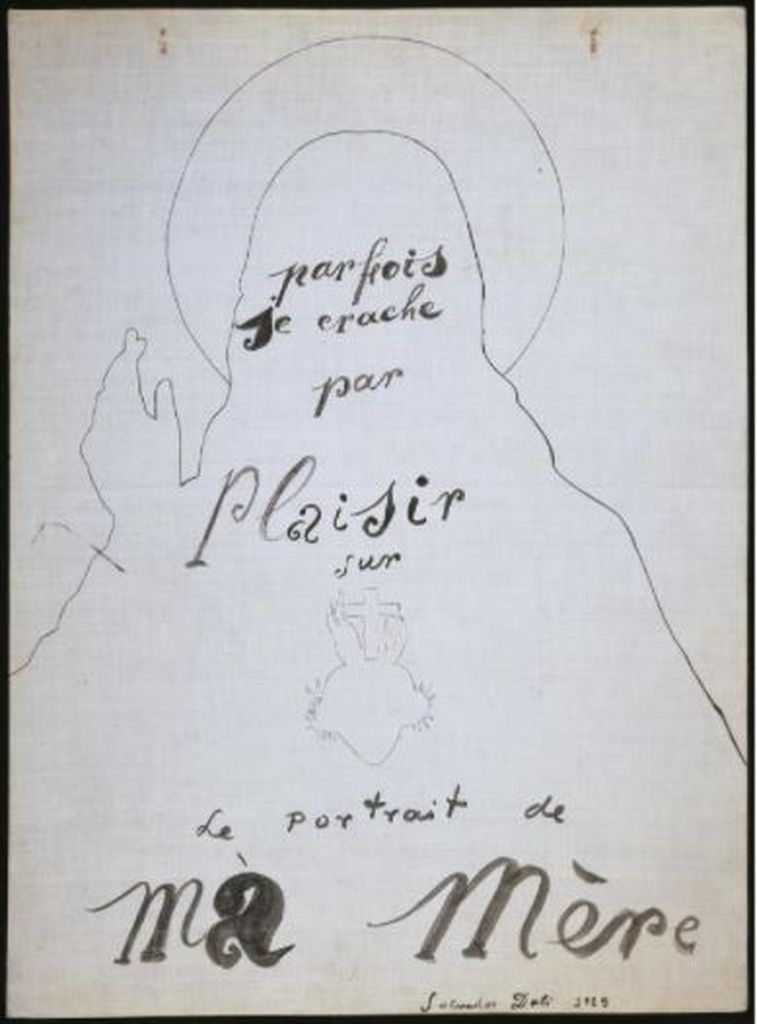

His infatuation with Gala, however, was not the final strike that concluded his time in Cadaqués. The second reason involves an exhibition at the Goeman’s Gallery in Paris November 20th 1929. Of the works exhibited, a drawing titled The Sacred Heart, 1929 was displayed which featured the following sentence: “Sometimes I spit for PLEASURE on the portrait of my mother.” His mother, Felipa Domènech passed from Uterine Cancer Feb. 6, 1921, and he describes her death in The Secret Life as “the greatest blow I had experienced in my life” (p.152). His family considered this an insult to his mother’s memory, and as a result, he was immediately exiled from Figueres. He was not, at this point, also exiled from Cadaqués, and he was sent there to reflect on his actions. This changed when a few days later, Dalí received a letter alerting him that he was no longer welcome at their summer home. From then onward, his father made it incredibly difficult for him to stay for any period of time in Cadaqués even if he was just passing through.

Dalí’s final thoughts on Cadaqués: “The road that goes from Cadaqués and leads towards the mountain pass of Paní makes a series of twists and turns, from each of which the village of Cadaqués can be seen, receding farther into the distance. One of these turns is the last from which one can still see Cadaqués, which has become a tiny speck. The traveler who loves this village then involuntarily looks back, to cast upon it a friendly glance of leave-taking filled with a sober and effusive promise of return. Never had I neglected to turn around for this last glance at Cadaqués. But on this day, when the taxi came to the bend in the road, instead of turning my head I continued to look straight before me” (The Secret Life of Dalí, p.254).

Cape Creus

“Each hill, each rocky contour might have been drawn by Leonardo himself! Aside from the structure there is practically nothing. The vegetation is almost nonexistent. Only the olive-trees, very tiny, whose yellow-tinged silver, like graying and venerable hair, crowns the philosophic brow of the hills, wrinkled with dried-up hollows and rudimentary trails half effaced by thistles.” –Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, p.128

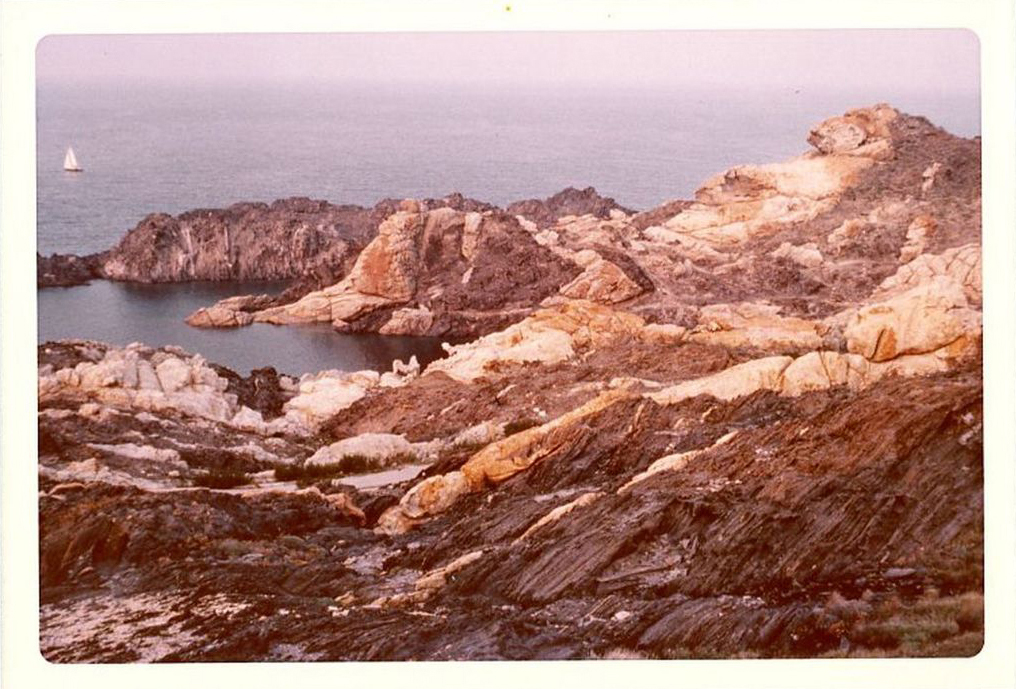

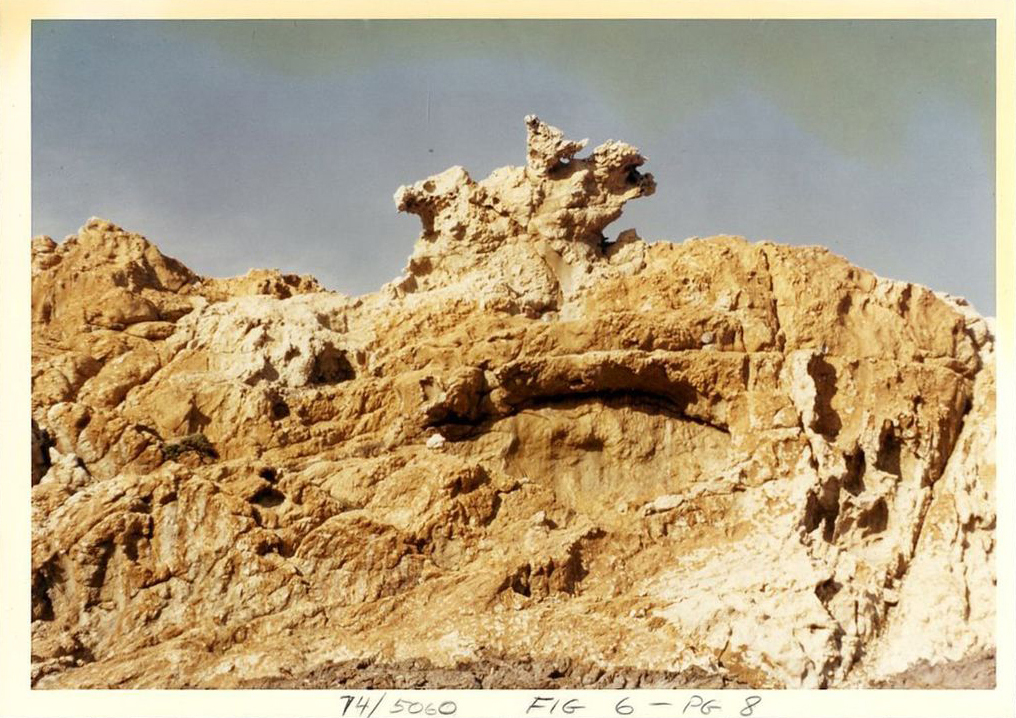

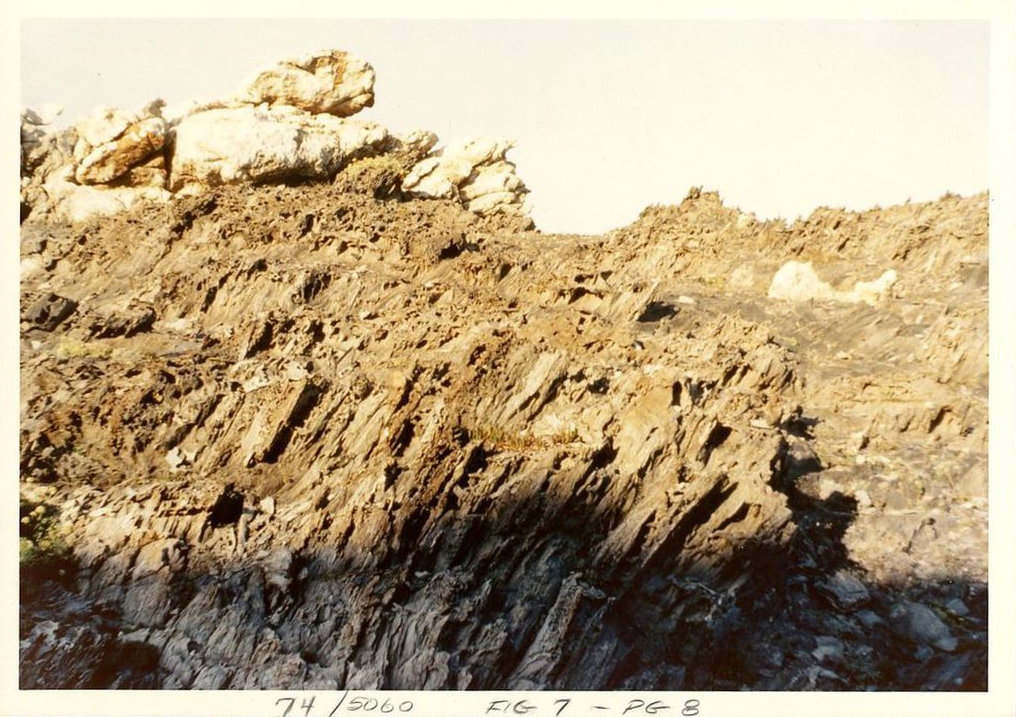

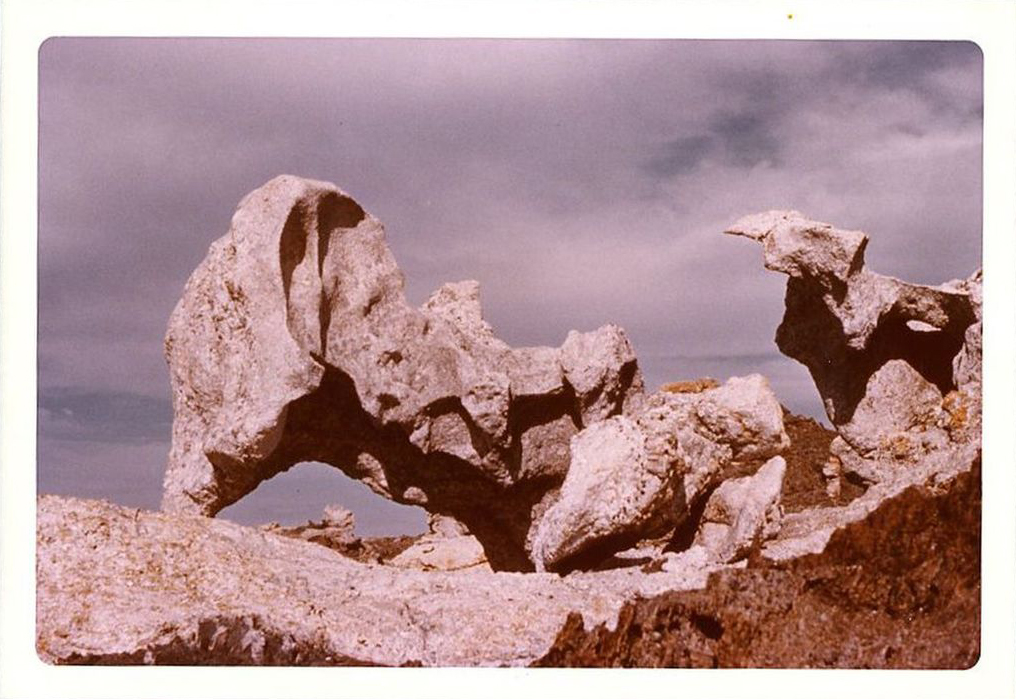

During their summer vacations, the Dalí family did not stay solely in Cadaqués. The family also had a tendency to make boat trips to Cape Creus, taken there by the family’s boatman, Enriquet. Declared a national reserve in 1998, Cape Creus is a peninsula located at the easternmost point of Spain, south of the French border. Coupled with sea erosion, the Tramuntana, a romanticized wind native to Catalonia, is the main cause responsible for shaping the landscape of Cape Creus. Blowing strongly at 80 mph, the Tramuntana is known to throw cars into the nearby sea, and force anyone who is willing to risk the wind to carry bricks in their pockets to weigh themselves down.

At one point, villages along this coast were all remote fishing villages. To aid in finding their way home, the fishermen would identify and name the rocks on the coastline to landmark their path. The Eagle, the Seal and the Old Man are a few examples of this, and the combined efforts of the sea erosion and Tramuntana certainly made more than a few optical illusions.

“The most beautiful spot of the Mediterranean lies just between Cape Creus and the Tudela Eagle (Àliga de Tudela).” Diary of a Genius, p.87

These optical illusions greatly impacted his work further down the line, but he did not make the connection of optical illusions to double images on his own. Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting (1632), and what he gleaned from it, is what solidified the connection. In the Treatise, da Vinci argued that landscapes, people, or fantastical scenes even, could be found in ordinary objects. He did not explicitly state that he was describing optical illusions, but Dali nevertheless made that connection. In his many writings, Dali does recount times where he was looking at one thing and saw another as da Vinci argues can be done. Da Vinci’s Treatise, and his memories, combined with the optical illusions of Cape Creus gave birth to Dali’s signature “Paranoiac-Critical Method”, a term he used to describe his double-image paintings where one image hides a second image.

He describes this process of observing and finding double-images in his 7th Secret from his 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship (p.61): “You must therefore know, young painter, that the Seventh Secret of your art resides in the sympathies and antipathies of your retina, in the manner in which you daily nourish it. For this you must surround it, as habitually as possible, with a propitious environment, with favorable retinal company, capable of serving as, of performing the office of, a kind of continual mosaic, persisting invisibly in the depth of your retina against which you will see real, full figures stand out more sharply.”

Of the number of identifiable rock formations at Cape Creus, the Head of Culleró was the rock more often than not referenced in Dalí’s work

This particular formation was first depicted in The First Days of Spring, and this was not its’ final appearance. Dalí adopted the rock formation as a personified, self-portrait which is identifiable in the following works: The Great Masturbator, Memory of the Child-Woman, Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, Profanation of the Host, Untitled (Iceberg) and Fantasies Diurnes. Louis Pauwels, a French writer who visited Dalí in the summers of 1966 and 1967, wrote that “Dalí… could only be fully understood if one took into account this extraordinary landscape that had shaped his thinking.”

Port Lligat, Spain

“[Port Lligat] was where I learnt to become poor, to limit and file down my thoughts so that they would acquire the sharpness of an axe, where blood tasted of blood and honey of honey. A life that was hard, without metaphor or wine, a life with the light of eternity” (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, p.7).

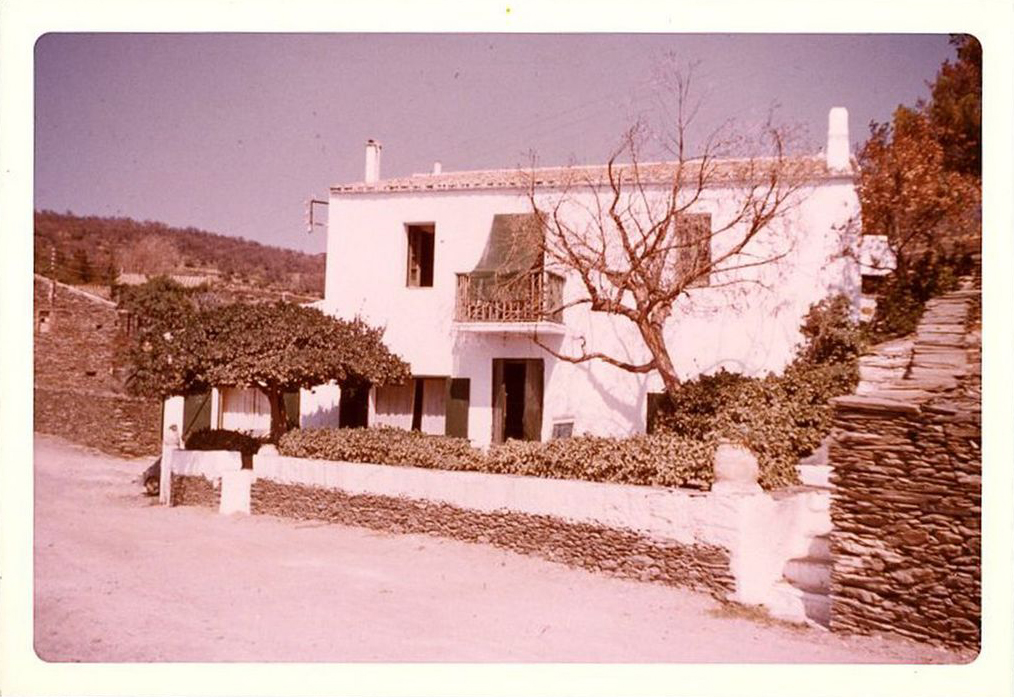

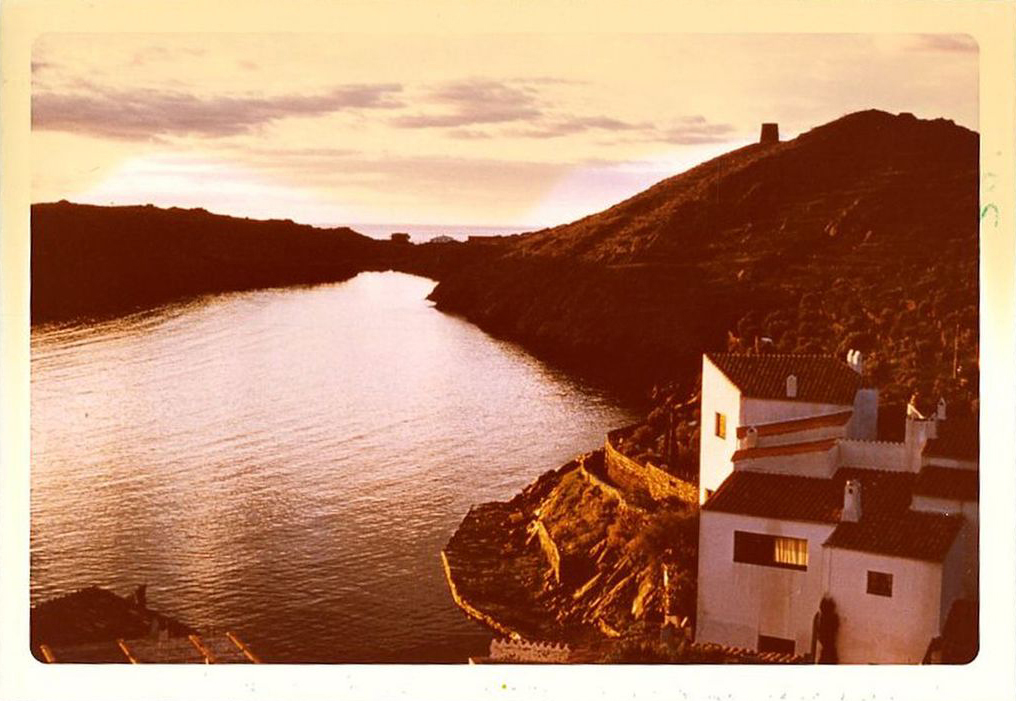

Now expelled from the family home, Dalí fled Cadaqués and sought refuge with Gala in Paris. Not too long after, because Dalí did not want to break the ties with the landscape that inspired him so much, he contacted Lídia Nogués, a local from Port Lligat and someone he had gotten to know quite well during his life in Cadaqués. Despite not having the best reputation, she owned, or at least had connections to, a number of properties in the area. On the shore of the tiny fishermen’s village of Port Lligat, twenty minutes from Cadaqués and at the foot of Cape Creus, Lídia’s sons owned a crumbling shack with a collapsed roof where they kept their fishing gear. “With the capriciousness which always characterizes my decisions,” Dalí writes in The Secret Life, “it became in a moment the only spot where I would, where I could, live. Gala wanted only what I wished.” A letter asking to purchase the shack was sent to Lídia, who replied favorably, relaying that her sons agreed to let him have the cottage (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, p.244).

“I am not at home except in this place. In any other place I am just passing through.” – Salvador Dalí

With financial assistance from his wealthy patrons, the Noailles, the first hut was purchased in 1930. This original hut was one small (236 sq. ft.) room and had no electricity. If they wanted water they had to pump it from a nearby well (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle 102).“None of the palaces of Louis II of Bavaria aroused in his heart the yearning that this little cottage inflamed in Gala’s heart and mine” (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle p.166). Not too long after, a second hut was purchased and officially fitted to the existing home in 1932. From then on over forty years, the Dalís continued to gradually expand their home by purchasing nearby cottages and affixing them to the original hut. Once attached, the Dalís would then transform the new additions into whatever they required. The final product of this endeavor is pictured to the left. A loose timeline of when huts were acquired follows below.

- 1930 – First shack purchased

- 1932 – Second shack purchased

- 1935 – Started to purchase nearby properties to append to the existing structure.

- March 1936 – With help from generous patrons Edward James and Lord Berners, Dalí received 10,000 francs to put towards what would’ve been another shack that would’ve been added to the existing house. This ended up not going to plan and instead, the Dalí’s hired Emilio Puignau, a Port Lligat local, to add a new storey to one of the existing buildings (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí p.352-53).

Hiring Puignau was not a one time deal. The Dalís and Puignau entered an arrangement of sorts and for the first decade of their working relationship, Puignau would either enlarge or improve their home during the Dalís absences. Dalí poetically likened their home to a cell’s structure: “Our house had grown exactly like a real biological structure, by cellular budding. To each new growth our life corresponds to a new cell : a room. The nucleus was the paranoiac delirium of Lídia, who made us a gift of the first cell” (The Wonderful World of Salvador Dalí, p. 26).

Additionally hired to help maintain the property was Arturo Caminada, a fourteen year old Cadaqués local who was hired specifically to look after the Garden and the boat. Caminada remained with the Dalí’s for thirty seven years and never once outsold the Dalís. After they had both passed, the newly established Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation hired him to continue to look after the properties, which was a short-lived arrangement as Caminada died less than two years after Dalí in 1990 of what the locals claimed was a broken heart.

Starting in 1949, the Dalís implemented a timetable for their various residences that they would maintain for roughly 30 years. Winter was split between Paris (Le Meurice) and New York (St. Regis) and the remaining seasons were spent at their home in Port Lligat. Of all the unique features of the Port Lligat home, there are several worth noting.

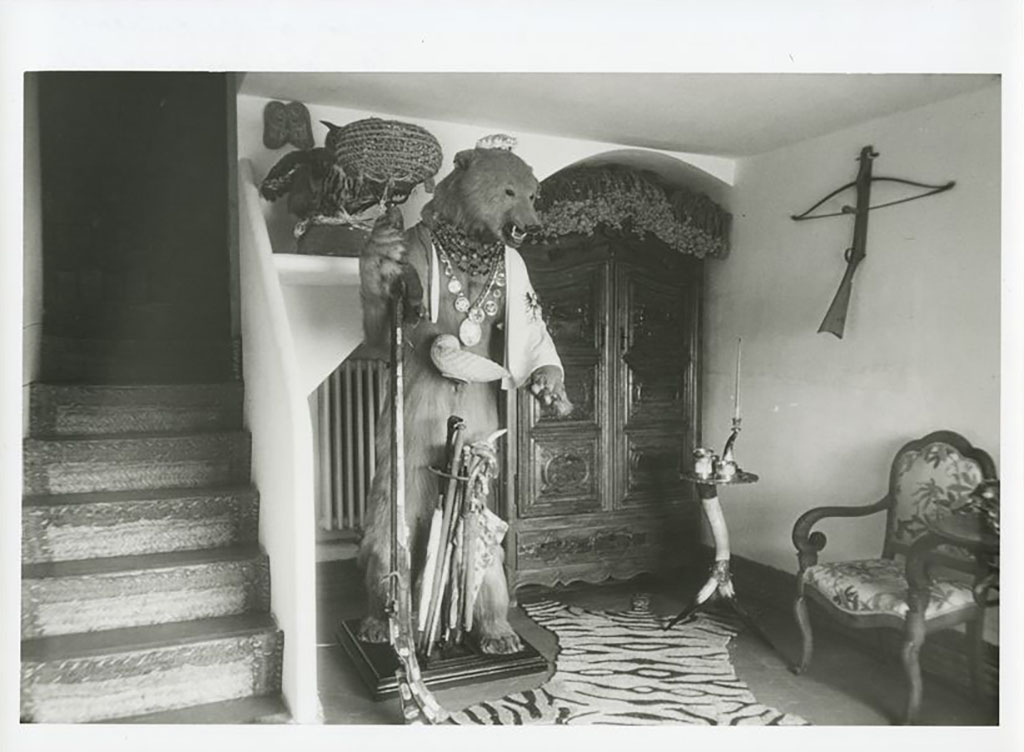

Bear Hall

Named for the large, looming taxidermy bear, Bear Hall is the first room in the house. A gift from one of Dalí’s famous collectors, Edward James, It originally arrived dyed purple, much to Dalí’s delight, and when the purple faded due to sun exposure, Dalí pledged to dye it green, which he never followed through on (The Wonderful World of Salvador Dalí, p.125). The stuffed bear was not just a conversation piece however, and did have multiple purposes, once serving as an umbrella stand, letter holder, harquebusier and as a lamp (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, p.100). The bear, while multifunctional, also sent a very clear message to their guests, reminding them not to overstay their welcome. As kind as the Dalís were to their visitors, they were incredibly protective of their privacy and never allowed any of their guests to stay overnight.

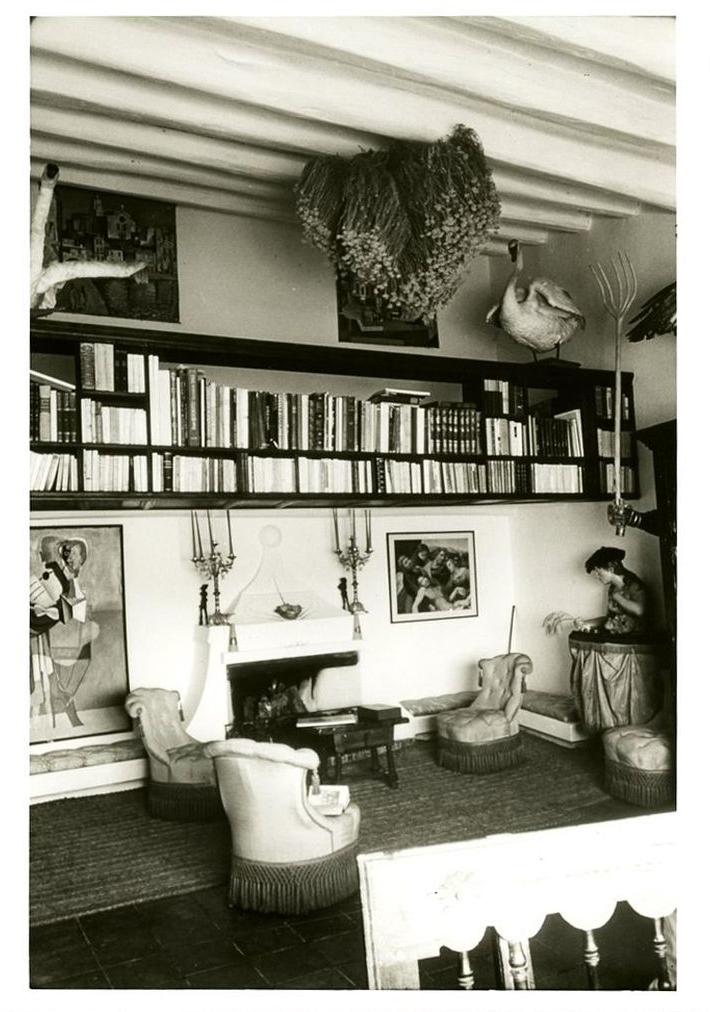

Taxidermy and Preservation

Bear hall was not the only room in the house with a large, looming taxidermy animal. The Dalís Library featured stuffed swans, located on top of the bookcase. During their lifetime, they swam in the Bay of Port Lligat and Dalí was very fond of them. He once explained of his house “Here in this house, everything is preserved” (Dalí The Empordà Triangle, 100). Not only did the home preserve animals, but plants as well. Gala’s favorite flower was the Houseleek, seen here in the Library, and she decorated their home with large, dried bundles of them.

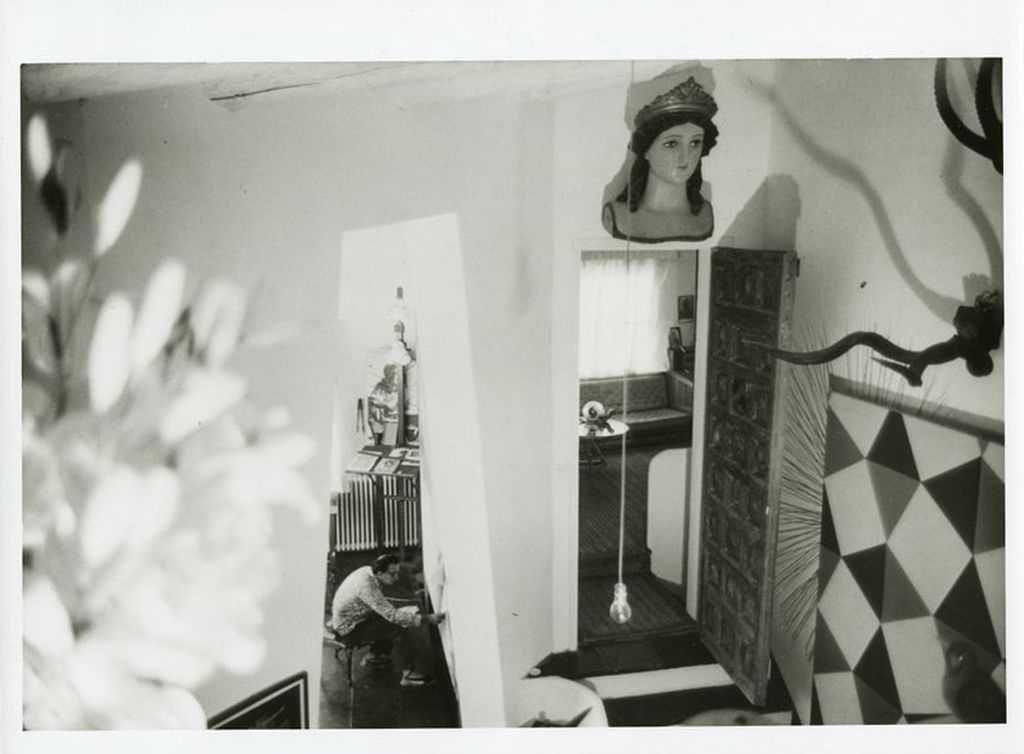

Dalí’s Studio

Of the many rooms that composed the Port Lligat labyrinth, the studio was where Dalí could be found more often than not. Prior to 1950, he used other rooms of the house, but once the studio was completed he used it definitively. Dalí took his work very seriously, starting at dawn and not finishing until the sun had set, only taking short breaks to swim, eat and have an afternoon nap (Dalí, The Empordà Triangle, 101). A strange feature of their home that is noticeable in this photograph is the absence of doors. Due to the lack of privacy, Dali can be seen diligently working in the entryway to his studio.

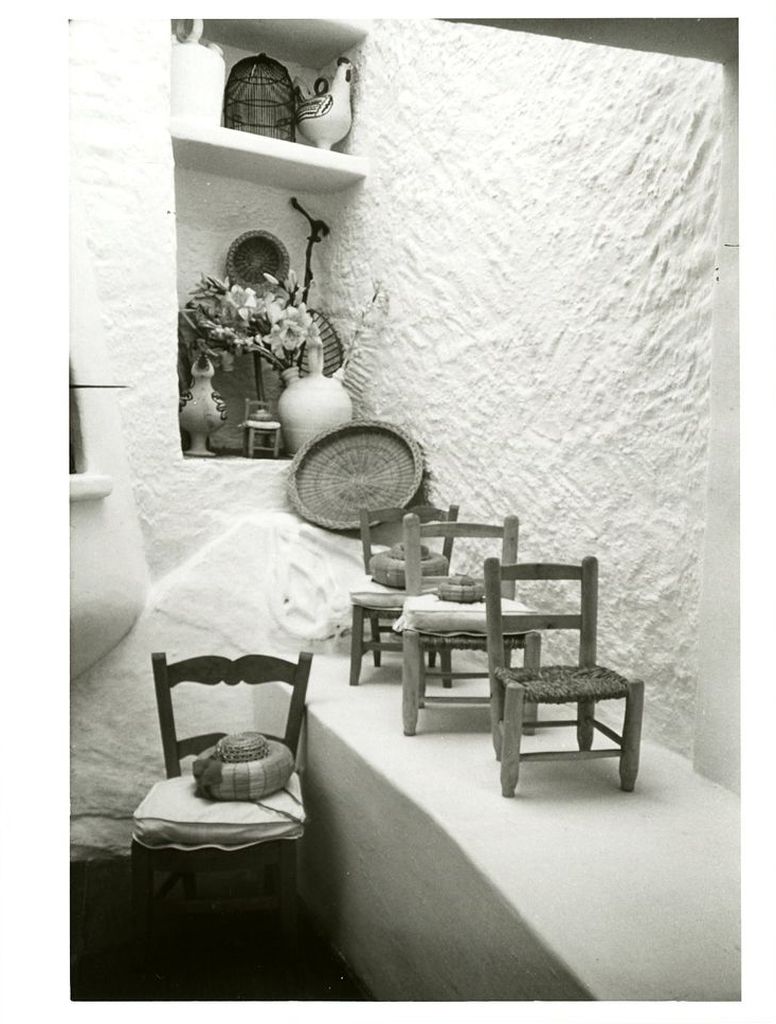

Kitsch and Knick-Knacks

Through their travels, the Dalís had ample opportunity to collect objects to display in their home. The rhyme or reason behind the collection of these objects is unknown, but an explanation of sorts is provided in his publication, Diary of a Genius. Dalí writes that on Sept. 6th 1956 he bought ten caps in Figueres simply because he had banged his head. The best example of their accumulated knick-knacks exists in their dining room, where they used the alcoves and ledges to display their finds. Another example: “My great desire is someday to fill all these fishermen’s huts with the perforated mosaics of millions of minicards” (The Wonderful World of Salvador Dalí, p.40).

Dalí, however did find chairs particularly fascinating. Specifically, chairs that are designed with one or more attributes that would make them difficult to sit in.

Barracks

Although never converted or assigned a purpose during Dalí’s lifetime, the barracks was also a notable purchase, and he bought it to keep it in its original state. This building is the subject matter of his 1954 painting Noon (Barracks at Port Lligat). This hut with the dry stonewall façade still intact, and the only building not drastically altered, currently houses the cloakroom of the House-Museum.

Conclusion

After Gala passed in 1982, Dalí returned briefly to Port Lligat, but left suddenly to live at Gala’s castle in Púbol where he lived for the next two years. He never returned to Port Lligat after that, and after an accident at the castle, lived the last five years of his life at his Theatre-Museum, now known as the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation. He did not return to Cadaqués either. His sister, Anna Maria, did indeed inherit their summer home and held a private mass for him there after his death.

A lighter, more fitting note to conclude with would be with one of the final quotes from Ian Gibson’s The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí: “…to the landscape of the Upper Empordà that Dalí always admired fanatically from childhood and with which he will always be associated: Cadaqués, Port Lligat and the mineral wilderness of Cape Creus, that weird theatre of optical illusions which taught him that something can be something else, and where, one springtime day in 1925 he, Anna Maria and Lorca had munched their sandwiches beneath The Eagle.”