Aimé Césaire: Poetry, Surrealism and Négritude

This exhibition celebrates the Martinique poet, scholar and politician Aimé Césaire (1913-2008), who founded the “Négritude” movement. It explores Césaire’s remarkable life, his accomplishments as a writer, and how Surrealism influenced his ideas about “Négritude,” anti-colonialism and Black identity.

As a Black surrealist writer, Césaire holds a prominent historical position. This exhibition builds on previous Dalí Museum exhibitions that focused on non-European artists’ dialogues with Surrealism, including Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (2008), Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (2016), and photos of Kahlo with her husband Diego Rivera (2020).

This exhibition is co-curated by Bob Devin Jones, Founder and Artistic Director of Studio@620, and Peter Tush, Dalí Museum Curator of Education. Listen to the two audio stops, narrated by Bob Devin Jones, available for download on the Dalí Museum App.

See Aimé Césaire: Poetry, Surrealism and Négritude in person Sep 10, 2021 – Jan 2, 2022 and visit our calendar of events for information on the numerous exhibit-related programs scheduled at both Studio@620 and The Dalí Museum.

1. Revolutionary Poet and Politician

Aimé Césaire was a surrealist poet, lifelong politician and intellectual leader. With interests stretching from literature to political science to history, Césaire is particularly celebrated for his poetry, including Lost Body and Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, the latter described by surrealist leader André Breton as “nothing less than the greatest lyrical monument of our times.” Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that, “A Césaire poem explodes and whirls about itself like a rocket, suns burst forth whirling and exploding like new suns—it perpetually surpasses itself.”

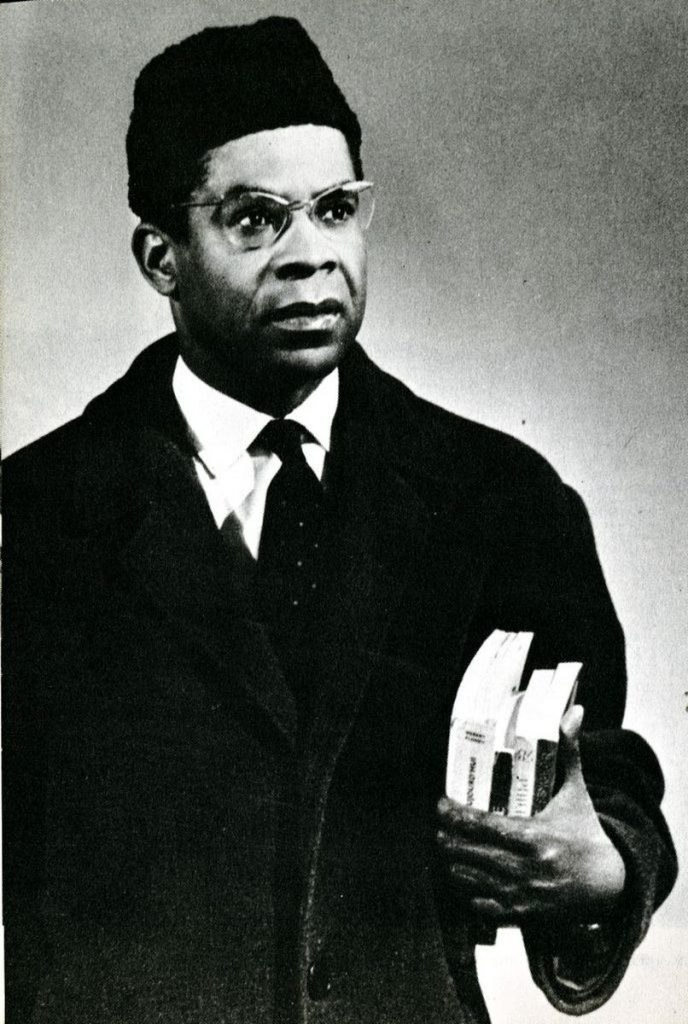

Born on June 26, 1913, in Basse-Pointe, a small coastal town of Martinique, Césaire’s father was a tax inspector and his mother a seamstress. One of seven children, he learned to read and write at an early age and excelled in the French public school system in Martinique.

In the 1930s, after receiving a scholarship, he traveled to Paris to attend the elite Lycée Louis-le-Grand and then France’s most prestigious liberal arts institution, the École Normale Supérieure. In Paris, Césaire helped create the student literary review L’Étudiant noir (The Black Student), where he coined the term “Négritude.” Négritude is an anti-colonial Francophone movement that embraces and celebrates Black identity. It seeks to unite those affected by the African diaspora through an understanding their shared history. For Césaire, the acceptance of “Blackness” was essential in order to “decolonize the mind.” After his Parisian studies, Césaire took a teaching position in Martinique in 1939. In 1945, with the support of the French Communist Party (PCF), he became the Mayor of Fort-de-France, Martinique, and deputy to the French National Assembly for Martinique. The following year, instead of rebelling for independence as Haiti did, Césaire guided Martinique to become a Department of France, something akin to Statehood. Growing disillusioned with the Soviet Union after the 1956 suppression of the Hungarian revolution, he resigned from the Communist Party and later established the Martinique Independent Revolution Party. He retired from politics in 1993 after serving 47 consecutive years as Mayor and died in Martinique on April 17, 2008, age 94.

2. Négritude and Tropiques: Anti-colonialism in Paris and Martinique

While studying in Paris in the 1930s, Césaire befriended two fellow Black students, Léopold Senghor of Senegal, later the first president of Senegal, and Guyanese poet and politician Léon-Gontran Damas. Together, they created the journal L’Étudiant noir (The Black Student), a publication focused on their shared experiences and the history of colonization and slavery, a history largely ignored in the books they read. Damas described L’Étudiant noir as “…a corporative and combative journal which aimed to end tribalization and the clan system in force in the Latin Quarter! We ceased to be Martinican, Guadeloupean, Guyanese, African and Malagasy students and became one and the same Black student.”

L’Étudiant noir is where Césaire coined the term “Négritude,” which he defined as “the simple recognition of the fact that one is Black, the acceptance of this fact and of our destiny as Blacks, of our history and culture.” Drawing on both the dreamlike free associations of Surrealism and anti-colonial politics, Négritude is an anti-colonial movement focused on embracing and celebrating Black identity. Assuming the slave ship as common ancestry, Négritude aimed at raising and cultivating “Black consciousness.”

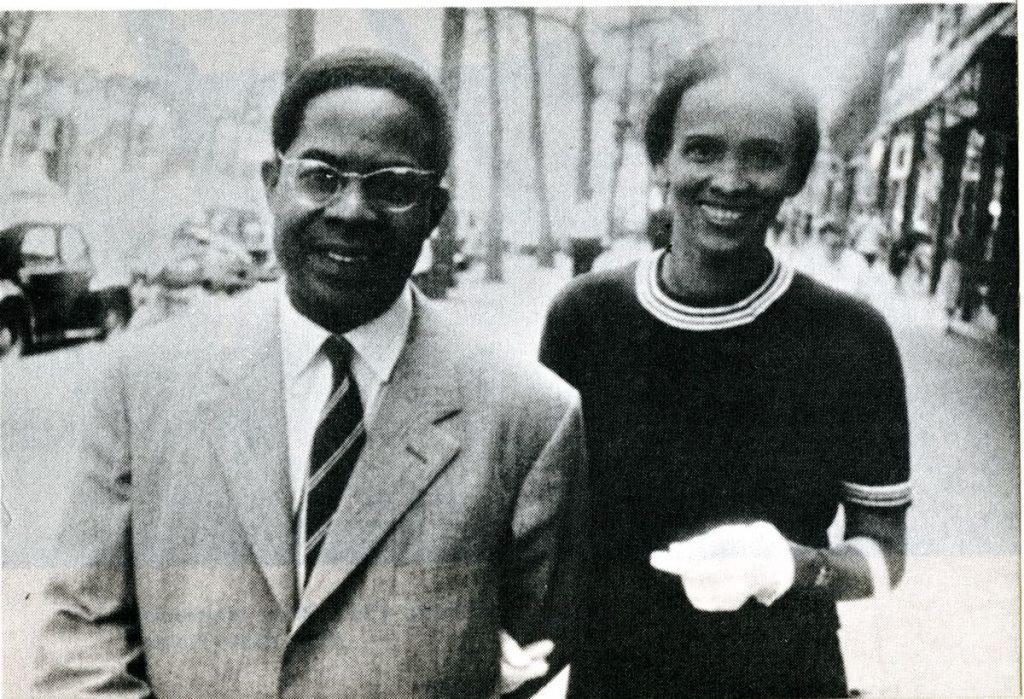

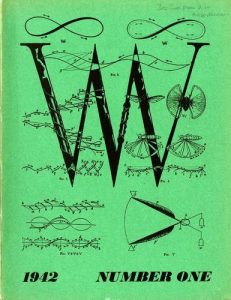

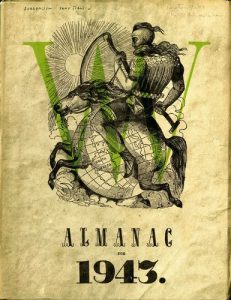

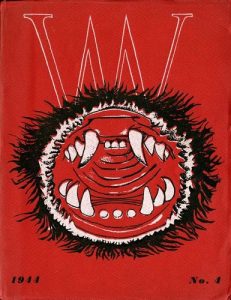

While in Paris, Césaire began work on Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, a vivid depiction of the ambiguities of Caribbean life and culture. During this period, Césaire also met Suzanne Roussi, whom he married in 1937. Returning with their first child to Martinique in 1939, they both took teaching positions in Fort-de-France. During the 1940s, Martinique fell under the control of the French Vichy Government, collaborators with Nazi Germany. In this repressive atmosphere, both Césaires and their friend René Ménil founded the Martinique periodical Tropiques (1941-45), an anti-colonialist journal drawing upon the irrational language and revolutionary aspects of Surrealism and dedicated to Black poetry.

Mixing European Surrealism with Négritude allowed Césaire and his group to express themselves creatively while attacking the Vichy regime and the racism of French sailors who frequented Martinique’s port. Following the war, Césaire published Discourse on Colonialism in 1950, a classic of political literature that would influence a generation of Black writers, scholars and revolutionaries. Césaire’s stance on colonialism is forcefully summarized in Discourse on Colonialism: “What am I driving at? At this idea: that no one colonizes innocently, that no one colonizes with impunity either; that a nation which colonizes, that a civilization which justifies colonization—and therefore force—is already a sick civilization, a civilization which is morally diseased, which irresistibly, progressing from one consequence to another, one denial to another, calls for its Hitler, I mean its punishment.”

3. Césaire Encounters André Breton: Surrealist Freedom

Throughout the 1930s, Surrealism rejected the values of colonial Europe, denouncing colonialism in its writings and garnering admiration from the poets and intellectuals in the French-speaking Caribbean who were leading the anti-colonial resistance.

In 1941, André Breton, his family and 350 leftist exiles boarded a ship in Marseille to seek asylum in the U.S. They disembarked in Martinique for a month. Upon arrival, the Vichy authorities confined them all to house arrest, and Breton—singled out as a “dangerous agitator”—was placed in an internment camp. After a week of hostilities and depravation, the Bretons were released. After this ordeal, Breton, along with his friend André Masson and the Cuban surrealist painter Wifredo Lam, began exploring Fort-de-France.

On one of these excursions, Breton stumbled upon the periodical Tropiques. Deeply moved by what he read, Breton immediately arranged to meet with the Césaires and René Ménil. Breton was even more elated when he read Césaire’s Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. In a subsequent edition, Breton added an introduction, stating, “I could not believe my eyes: For what was said was what had to be said… . All the grimacing shadows were torn apart, scattered; all the lies, all the mockery shredded: Thus the voice of man was in no way broken, suppressed—it sprang upright again like the very spike of light.”

Césaire introduced Breton, Masson and Lam to the beauty of the island, and they met many times before Breton and Masson continued on to New York and Lam to Cuba. Moved by the beauty and mystery of the lush island, as well as the dreamlike visions of Césaire, Breton published Martinique Snake Charmer with its “Creole Dialogue,” co-authored with Masson and featuring Masson’s illustrations.

For Césaire, the meetings with Breton were crucial. “If I am who I am today, I believe that much of it is due to my meeting with André Breton. [His presence was like] a great shortcut towards finding myself.” Suzanne summarized her view of the political importance of Surrealism: “Now that in 1943 freedom itself is under threat throughout the world, Surrealism, which has never for one moment ceased to serve the cause of man’s emancipation, can be summed up wholly in that one magical word: freedom. Throughout these hard years of Vichy domination, the image of freedom has never completely faded here, and we owe this to Surrealism.”

In addition to his friendship with Breton, Césaire formed a lifelong friendship with Lam. Lam said that they were “instantly taken in by each other” and saw themselves as “brother artists.” Césaire introduced Lam to the lush Martinican forest of Absalon, profoundly affecting the painter and leading to his most celebrated painting, The Jungle, in 1943.

4. Césaire’s Poetry: Notebook of a Return to the Native Land and Lost Body

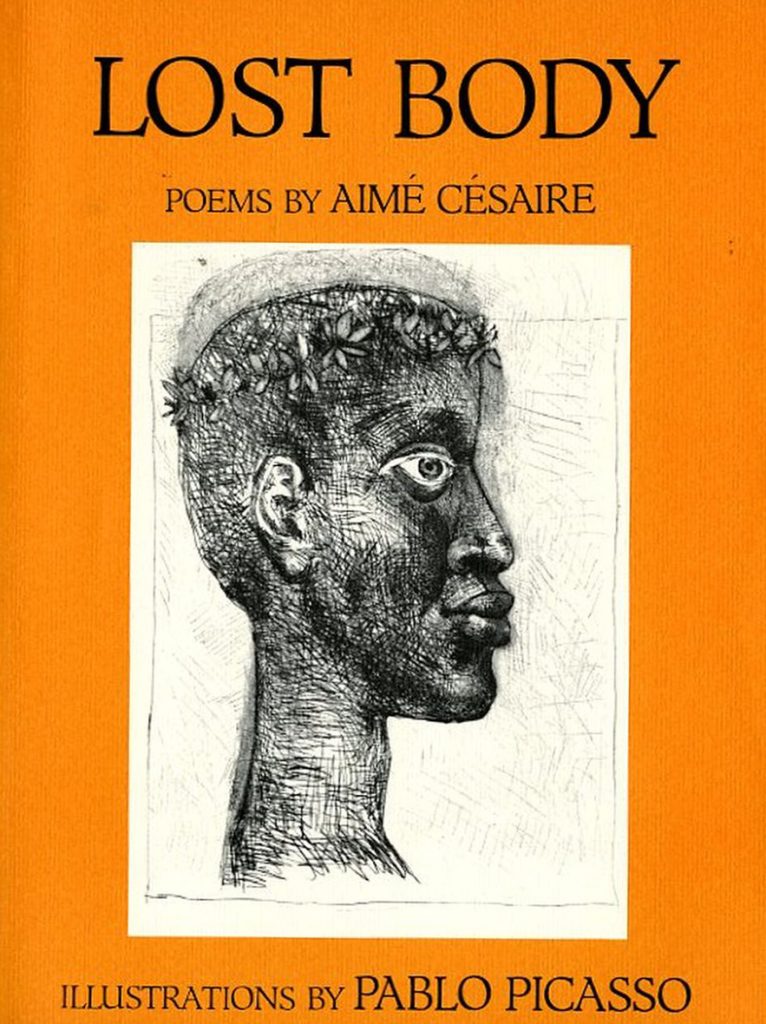

Published by George Braziller,

Inc., U.S., 1986

Collection of The Dalí Museum

Library & Archives

Césaire was able to balance his life as a political leader with his celebrated career as a writer. He wrote several important works for the stage, including his Shakespearian response A Tempest and the political tome Discourse on Colonialism, but Césaire is most celebrated as a poet. His two best-known works are his 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land and his 1950 Lost Body, and this final section focuses on these two key poetic masterworks.

While vividly describing his experiences with colonial Martinique, Césaire’s poetry drew extensively from the surrealists and their precursors, particularly Arthur Rimbaud, Comte de Lautréamont and Charles Baudelaire. His poetry employs key techniques of Surrealism, including personal symbolism, the alchemy of language, free association, personal mythology, the Marvelous, black humor, hermeticism and the self-alienation of Rimbaud’s “I is someone else.” In addition, metamorphosis is a defining feature throughout Césaire’s poetry, and his work is filled with numerous transformations from human to vegetal and animal forms. Such surrealist techniques are employed extensively in Notebook and Lost Body.

Notebook was published just before Césaire returned to Martinique at the beginning of World War II. It is a focused development of his concepts of Négritude, an affirmation of Black identity, history and culture in response to a history of French racism and colonialism. It presents a vivid, brutal vision of the ambiguities of Caribbean life and culture in the New World and is considered a turning point in French Caribbean literature.

In his introduction to the poem, Breton says, “If the slave traders have physically disappeared from the world’s stage, their vile spirit is undoubtedly still at work. For just as their ‘ebony wood’ became this slap dash cargo, not even good enough to rot in the hold of their ships, so our dreams, that better half of our nature, become disenfranchised.” Passages from Notebook appear on the adjacent panel.

In 1948, Césaire met the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso at the Communist-led World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace. Picasso and Césaire immediately bonded, discovering a shared interest not only in Communist politics and African art but also in Surrealism’s fascination with dreams, the power of the unconscious mind, the irrational and fantastic. Together, they jointly published Lost Body in 1950, with 10 poems by Césaire and 32 images by Picasso. Césaire’s poems challenge society’s depiction of the Black man as half-human and half-beast, while Picasso’s illustrations fuse male and female sexual organs with plant-inspired forms. Picasso’s frontispiece is a large head of a poet crowned with a laurel wreath—a celebration of Césaire.