An Overview

When Salvador Dalí & Luis Buñuel’s film Un chien Andalou premiered in the City of Light, Paris was an avant-garde hothouse rife with artistic conflict and friendly rivalry. Midnight in Paris: Surrealism at the Crossroads, 1929 examines this particularly rich and vital creative era by examining the works, friendships and clashes of Jean Arp, André Breton, Luis Buñuel, Alexander Calder, Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, René Magritte, Joan Miró, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy and others. Through a host of 20th-century works from the renowned Centre Pompidou in Paris, Midnight in Paris, 1929 brings to life the personal relationships and the intellectual passions that threatened to tear apart the newly formed artistic movement called Surrealism.

Setting the Stage: Surrealism a Century Ago

Surrealism was born from the minds of André Breton, Philippe Soupault, and Louis Aragon in Paris in 1924. The three poets would soon be joined by other writers, artists, and filmmakers who similarly sought to liberate themselves from rational control, and wished to put imagination at the basis of their work. In this creative pursuit, they experimented with psychological theories about automatism, dreams, the unconscious, and psychoanalysis. In the history books, the year 1929 is most often associated with the financial crisis that erupted on Wall Street and rippled through the world’s economies. For surrealism too, 1929 was marked as much by crisis as by innovation.

Audio narration by Eugenie Bondurant.

(Brașov, 1899 – Beaulieu-sur-Mer, 1984)

Eiffel Tower

ca. 1930–1932

Gelatin silver print

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Purchase, 1997

Paris 1929 & Surrealism at the Crossroads

Welcome to our exhibition Midnight in Paris: Surrealism at the Crossroads, 1929. created in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou in Paris, France’s National Museum of Modern Art, and by the Members of The Dalí Museum, The Trustees, the Guild, Mrs. JeanFrancois Rossignol and Mrs. Timothy R. Ranney. You have entered through a Paris Metro stop and are now in Paris in 1929. Paris, a city that is always filled with light and shadow, always both intellectual and sensuous, was rife with artistic alliances, conflict and rivalry. Art itself was at a crossroads, unsure of its path forward, embroiled in arguments over the supremacy of various media, with everyone competing for attention. Would painting survive the new experiments with photography, film and collage? Would politics replace art? 1929 represents the moment of a crisis of thought and artistic strategy, with lasting consequences for art. Along the various Surrealist-inspired avenues, you will meet the avant-garde artists during this period of experiment and uncertainty. You will discover the work, friendship and clashes of over 20 artists of the era, ranging from the painters Salvador Dalí and Renee Magritte to sculptors Hans Arp and Alexander Calder, and filmmakers Germaine Dulac and Luis Bunuel.

(Lessines, 1898 – Brussels, 1967)

The Red Model

[1935]

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Purchase, 1975

The “Oneiric” Image: Magritte’s Red Model and Dalí’s Hand

A term often used by the surrealists was “oneiric.” It means “dreamlike.” The spontaneity of “automatic” imagery, where an artist lets their unconscious create, was valued in Surrealism’s first phase. Now surrealist leader André Breton believed the movement’s future lay in dreamlike, “oneiric” images, that capture collective desires. René Magritte’s Red Model and Salvador Dalí’s The Hand – both express this dreamlike quality through transformation or exaggeration. Both artists use realism, to undermine reality itself. Hoping to get closer to the surrealist circle, Magritte moved in 1927 to Paris. His used a dreamlike style to create poetic associations established between otherwise dissimilar objects. The Red Model presents a pair of shoes that have become one, with the wearer. The shoes, which normally protect the feet, become the feet. Undermining the separation between human and object, between outside and inside, Magritte creates a monstrous, threatening transformation. When Dalí arrived in Paris in 1929, he promptly met Magritte. The success of Magritte’s images assured Dalí that his own dreamlike landscapes had a place in the Surrealist Movement. Dreams becomes political in The Hand, Dalí’s portrayal of the 19th century Catalan writer, Serafí Pitarra. Dali detested Pitarra because his writing was traditional, classical and rational. The painter humiliates the writer by presenting him in trousers smeared with excrement, and with a comically bloated hand. The hand is Dalí’s symbol for masturbation.

See also: Salvador Dalí’s The Hand

(Philadelphia, 1890 –Paris, 1976)

Idole de pêcheur

Fisherman’s idol

[1927] Bronze

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

State purchase, 1976

Surreal Sculpture: Man Ray

This dark bronze, totem-like statue is by Man Ray. Along with Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, Man Ray was part of the New York Dada group. He became part of the Paris Surrealist group in 1925. This sculpture is Fisherman’s Idol, an assemblage of wood and cork found on the beach, cast in bronze. The bronze endows the work with a presence, the original materials couldn’t offer. The resulting shape evokes primitive sculptures of gods, or talismans worn by sailors, as protection against the perils of the sea. Along with Jean Arp’s sculpture, this work evokes the arts of Africa and Oceania, prehistoric petroglyphs and pictograms on stone, all admired by the Surrealists.

(Figueras, 1904 – 1989)

Dormeuse, cheval, lion invisibles

Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion

[1930] Oil on canvas

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donated by the Association Bourdon

Dalí’s Paranoiac-Critical Method: Invisible Woman

Dalí arrived in Paris armed with ideas to share with the Surrealists. One of Dalí’s most important ideas is the “paranoiac-critical method.” Dalí defined this as a “spontaneous method of irrational knowledge, based upon the interpretive-critical association, of delirious phenomena.” This complex definition is clever. It refers to spontaneous creation – as in the automatic phase of Surrealist painting. But it adds interpretation, as in the dreamlike work that dominates Surrealism after 1929. This “paranoiac-critical method” often refers to Dalí’s double-image paintings, where a painting reveals two completely different images, depending on how you look at it. Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion, is one of Dalí’s earliest attempts at double-imagery. In this painting, Dalí creates three overlapping images. A boat is in the center. On its left is an egg shape, surrounded by golden hair. This is the head of a sleeping woman. Her arms drop to the floor. Her hips and legs are on the right. Look at this again, and the woman is a horse! Her arm becomes the horse’s forehead and muzzle; the horse’s nostrils are her opened fingers. Her hair is the horse’s mane. Her hips are the horse’s back legs, and the golden pattern to the right becomes the tail. A third figure is found in this same arrangement. The horse’s tail connects to a golden pattern that forms a lion’s head. The lion is the horse, reversed. The horse’s mane is now the lion’s tail. Through these changes, conflicting images arise. The double-image challenges our confidence in the stability of reality. Maybe the world really is as complex as this image, if we really look.

Photography

Surrealism had been initially preoccupied by the mind (“the functioning of thought”) in the mid-1920s, but by 1929 it turned towards the real and the relation of the mind to the real world. Photography offered a model by which to capture this “real” through a spontaneous mechanism, providing a mysterious access to the external world, one perhaps not obvious to the rational mind and eye. Photography was used to complement surrealist narrative and other texts, so as to associate thought and images. It was a way of engaging with the mysterious and little-known scenes of urban night life. In this way it performed a role similar to collage. Where fragments of the real become a means to summoning an imaginary image.

(Budapest, 1894 – New York, 1985)

Pavement, Paris

1929

Gelatin silver print

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Gift of the artist, 1976

Surrealism + Photography: Paris

For Surrealism, photography challenged the importance of painting. Photography can capture spontaneous and surprising moments of reality. Photography can reveal unconscious aspects of reality – an alternative view. Photography reinforced the Surrealists’ fascination with Paris. For the Surrealists, Paris was a living entity that mirrored their unconscious. They were fascinated by the haunted aspects of their city, places that seemed lost in time – the Passage de l’Opera, the arcades, the Metro stops, the flea markets. The immediacy of photography allows an unpremeditated image of reality, but it can yield a strangeness as powerful as any painting. Photographers Brassaï and André Kertész, while not officially surrealists, were friends with many in the group – and had an immediate impact. Their photos of mysterious Paris at night and the unusual views they captured of the Paris streets, reinforced Surrealism’s view that Paris itself was a forest of wonder and desire that contained an unconscious reality. Jacques-André Boiffard made mysterious images of Paris as well. His photos illustrate André Breton’s surrealist novel, Nadja. Brassaï’s graffiti photos, seen elsewhere in this exhibit, suggest that Paris could project haunting, cryptic messages for those open to it.

Dalí

In the spring of 1929, Salvador Dalí entered the scene of the Parisian avant-garde, accompanied by Luis Buñuel, a fellow Spaniard with whom he had recently created Un chien andalou. Dalí called their film “a dagger in the heart of the spiritual and elegant Paris.” The film was written following the surrealist technique of automatic writing. It caught the attention of the surrealists upon its release in June 1929, who praised the dreamlike character of its images and the poetic and psychoanalytic references. The film opened the door for Dalí to join surrealism and share with the movement his theory of “paranoiac critical method,” which consisted of juxtaposing unusual images to create “associations and delusional interpretations.” The Catalan artist opened his first Parisian exhibition on 20 November 1929 at Galerie Goemans. André Breton wrote the preface to the exhibition catalogue, which affirms the central role Dalí held in surrealism at this time. Dalí’s influence is particularly noticeable in the works of Yves Tanguy. Having joined the surrealist group in 1925, Tanguy’s previous preoccupation with automatism gave way to paintings depicting more dreamlike worlds, vast landscapes inhabited by biomorphic forms.

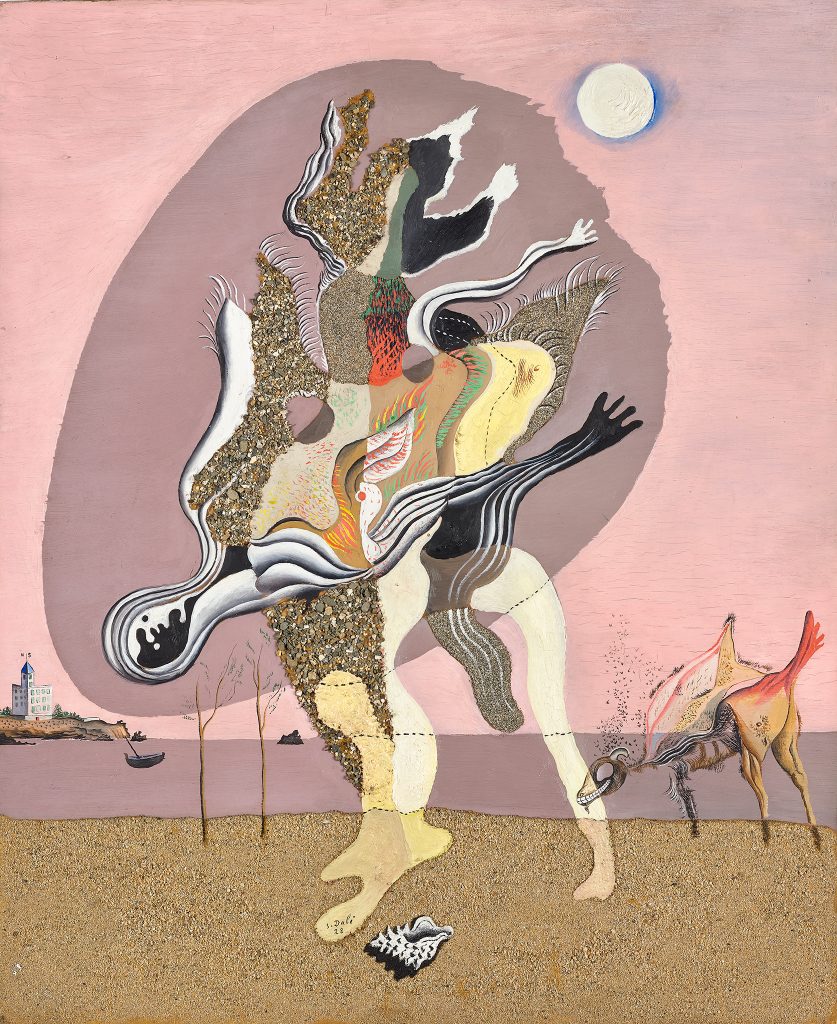

(Figueras, 1904 – 1989)

The Rotting Donkey

1928

Oil, sand and gravel on masonite

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donation / Acceptance in lieu, 1999

Dalí & Putrefaction: The Stinking Donkey

Decay became a cornerstone of Dalí’s painting and thinking in the late 1920s. It is expressed in the scene from Un chien andalou, the film he made in 1929 with Luis Buñuel. Two rotting donkeys are stuffed into pianos, one of the film’s cruelest and most fascinating elements. Clips of this film are presented in the film area of this exhibition. Dalí created this painting while under the spell of Surrealism, but before he travelled to Paris and met the Surrealists. He follows Miró’s example of mixing different styles and textures, arriving at a dreamlike fusion of realism and the fantastic The Stinking Donkey is also the title of the article where Dalí developed his “paranoiac critical” method in 1930, in the first issue of Le Surréalisme au service de la Révolution. When Dalí arrived in Paris in 1929, The Stinking Donkey won the esteem of Georges Bataille, who saw it as a reflection of his own violent concepts, and published an article about Dalí in his magazine, called Documents. Bataille broke away with a group of former Surrealists who rebelled against Breton’s doctrines. Unaware of the politics at the time, Dalí began his career with Surrealism enjoying the favor of their enemy Bataille, while being regarded with suspicion by Breton. Quickly, Dalí chose to align himself with Breton’s group.

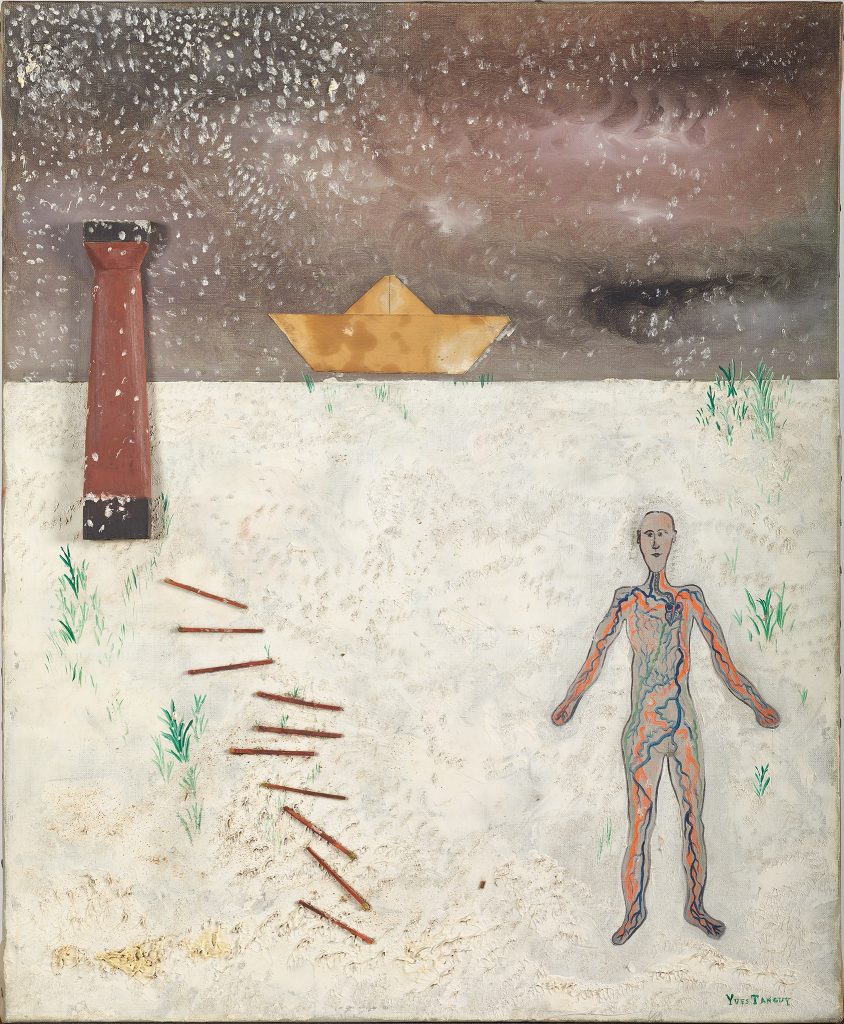

(Paris, 1900 –Woodbury, 1955)

The Lighthouse

[1926]

Oil on canvas with collage of matches, wood and origami

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donation / Acceptance in lieu, 2012

Dreamlike: Tanguy’s The Lighthouse

A merchant marine, Yves Tanguy was so moved when he encountered a painting by Giorgio de Chirico that he immediately decided to become a painter, even though he had no formal training. His studio on Rue du Château was a site for many Surrealist visitors, including Man Ray, André Masson and Francis Picabia. Through these contacts and the influential journal, La Révolution Surréaliste, his primitive painting evolved toward the dreamlike side of Surrealism. Though he was one of the first visual artists in the movement, Tanguy was dedicated to the dreamlike painting style of De Chirico. The Lighthouse shows the artist nude at the bottom of a ladder on a beach, perhaps on the coast of Brittany, France, where his mother lived. The matches glued onto the canvas reveal Surrealist influences: they resemble glued objects in Picabia’s paintings. The matches blazing in a man’s hair recall the early Surrealist film Entr’acte. And the small folded paper boat that sails through Paris in that film also appears on the horizon, in Tanguy’s painting.

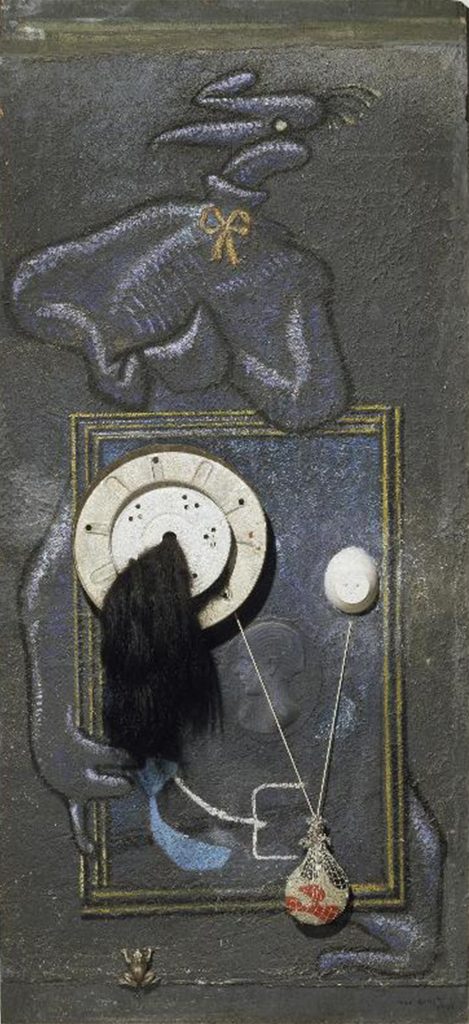

(Brühl, 1891 – Paris, 1976)

Loplop Introduces a Young Girl

1930/1966

Oil on wood, plaster and various objects

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Acceptance in lieu, 1982

Surreal Objects: Ernst’s Loplop Introduces a Young Girl

In the 1930s, the Surrealists were excited about constructing objects. These objects were not “artistic” like traditional sculpture. They were created to challenge reason and to summon subconscious associations. These objects were democratic – everyone could produce them by assembling found materials. This surrealist object reveals the dark humor of Max Ernst. “Loplop” is a recurring bird-like figure in his work. Dominant and enigmatic, Ernst established Loplop as his artist double, referring to it as “the Bird Superior.” All three Ernst works in this section feature the bird Loplop. In Loplop Introduces a Young Girl, an old door coated with plaster is the stage for a critical view of the art world. Here Loplop is a dealer selling gilded art. The framed “painting” Loplop presents is a sham – a metal wheel, a stone in a string bag and a horse’s mane. These objects aren’t beautiful – they assert their reality.

(Brühl, 1891 – Paris, 1976)

Chimera

[1928]

Oil on canvas, 114 × 145,8 cm

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Purchase, 1983

Automatic vs. Oneiric: Ernst’s Chimera

Max Ernst was a mercurial artist who often shifted his approach. He was comfortable with both automatic and dreamlike styles. His technique grew to include spontaneous methods like collage, grattage – or scratched imagery, and frottage – using rubbings, which were then used by other surrealists. Chimera is a painting generated by automatism, but the result is close to dreamlike. The chimera is a classical creature from the Iliad, described by Homer as “lion-fronted and snake behind, a goat in the middle.” The chimera became a protective deity of Surrealism. Here Ernst develops his own version, combining the figure of an eagle, with female breasts, a precursor to his own fantastic double, Loplop. Well aware of what Surrealism owed this ancient monster, Breton jealously preserved Ernst’s Chimera in the caverns of his studio.

Masson

André Masson had shared studio with Miró in the Rue Blomet at the beginning of the 1920s and was a major contributor to the development of automatic drawing and painting, sometimes verging on the abstract, but, as with Miró, Masson sought to invest painting with a visceral concern with life and death. Thus he brought the figure back into his dynamic compositions, as in his 1930 canvas Animaux Endormis (Sleeping Animals). An admirer of the pre-socratic philosopher Heraclitus, Masson saw life and painting as a rapidly flowing continuum. In his own words, “It was quite obvious that I found myself, with my quest for dynamism and the unstable, in a risky position.” This was also the intoxicated delirium of Dionysus as explained by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy. Masson’s slightly later sculpture Extase (Ecstasy) represents a figure born of such dynamic and irrational processes. And yet its composition allows for a sense of the poetic transparency that Nietzsche associated with Apollo’s rationality.

(Balagny-sur-Thérain, 1896 – Párizs / Paris, 1987)

Sleeping Animals

1930

Oil on canvas

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donated by Paul Rosenberg, 1947

Automatic vs. Oneiric: Masson’s Sleeping Animals

Automatic writing and drawing were embraced in the first phase of Surrealism. The Surrealists turned to automatism because they were suspicious of painterly technique, which they felt was at odds with the search for the unconscious. But by 1929, the “oneiric,” or dreamlike way of making art, was accepted as another way to explore the irrational. André Masson was a key practitioner of automatism. You will find several examples of his automatic drawings through this exhibit. But by the end of the 1920s, in works like Sleeping Animals, he shifts away from this spontaneous approach. His paintings became more painterly, with well-developed patterns depicting elemental forms. He began including human figures and addressing themes of life, death and sexuality.

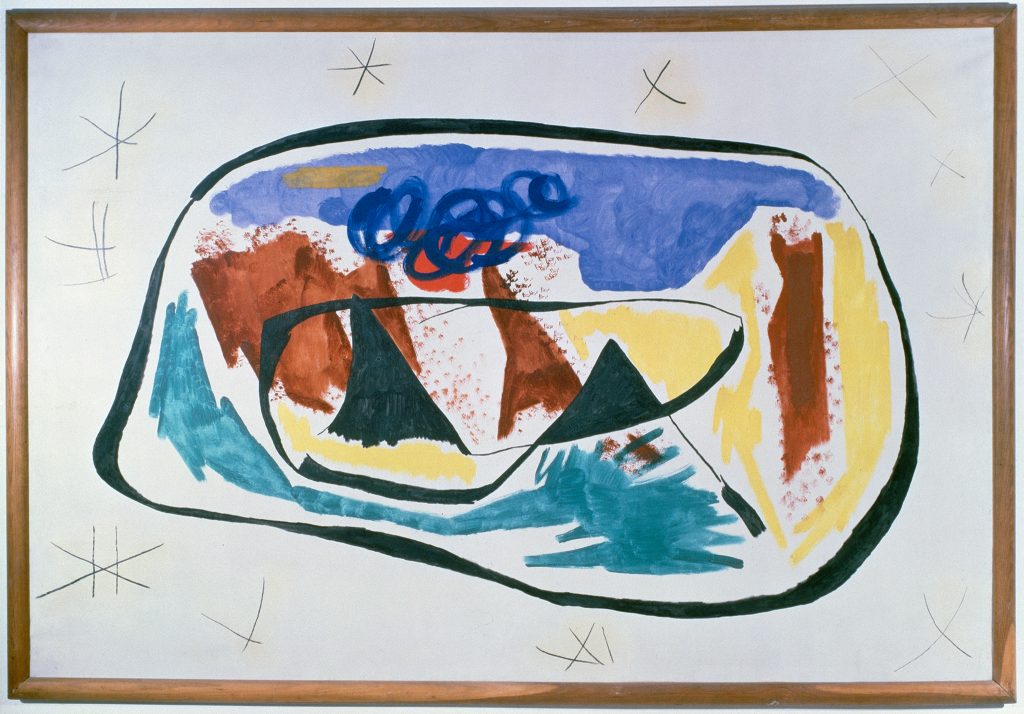

(Barcelona, 1893 – Palma di Mallorca, 1983)

Painting

1930

Oil on canvas

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donated by Mr. Pierre Loeb, 1949

Automatism: Miró’s Painting

André Breton founded Surrealism in 1924. His lofty definition for the movement was, “Pure psychic automatism, by which one seeks to express… the real working of the mind.” The word “automatism” is key. It means to perform actions without conscious thought or intention – to automatically create art. Surrealism grew from the group’s enthusiasm for Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. They felt that art could put people in touch with their unconscious, the realm of dreams. Automatic writing and drawing were popular in the early stage of the movement, when the Surrealists were suspicious of traditional painting techniques. Catalan Joan Miró, who settled in Paris in the mid-1920s, shared this distrust of tradition. Miró chose to pursue what he called an “assassination of painting,” to try to unlearn his formal training. Both prehistoric cave painting and the art of children appealed to Miró, and he set out to re-think what painting was. He introduced a symbolic language using visual gestures that echoed ancient alphabets, challenging assumptions about what painting should look like and how it tells a story. Miró imagined a dreamlike and poetic world far from early automatic work.

Nevertheless, Breton called Miró “the most beautiful feather in the Surrealist cap.”

(Strasbourg, 1886 – Basel, 1966)

Fruit of the Pagoda

[1934]

Plaster

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Seizure of the Customs Administration, 1996

Surreal Sculpture: Arp

These two white sculptures are by Jean Arp, one of the founders of the Zurich Dada movement in 1918. When Arp moved to Paris in the 1920s, his work became more sensual. He briefly joined with the Paris surrealists, and exhibited in their first exhibition in 1925. Arp’s work suggests the spirit of automatism, taking real life figures and reducing them to abstract forms. Pagoda Fruit is an imaginary fruit. The upper part of the work reminded Arp of the hooded roof of Chinese pagodas. He offered this analogy between organic material and the creative process – ‘Art is fruit that grows in man, like a fruit on a plant, or a child in his mother’s womb.’ Behind you is a third work by Arp – a blue and white wood relief. Head with Moustache and Bottles suggests a whimsy unusual within Surrealism. The painted wooded relief conjures up lips, eyes, a moustache, even breasts, from everyday objects like bottles and glasses. Head with Moustache and Bottles was reproduced in the rival surrealist magazine Document, suggesting the complexity of alliances and defections between the various artists in this exhibition.

See also: Jean Arp’s Head with Moustache

See also: Jean Arp’s Metamorphosis

Film

Building on the foundation of photography, the surrealists were among the first to see the power of the new cinematic medium. While they incorporated some experimental devices in their films, these filmmakers also drew on popular devices from commercial cinema (for example melodrama), and for this reason their works were all the more shocking, their screenings often provoking scandal. While the key practitioners of surrealist film were Man Ray, Luis Buñuel and Dalí, similar concerns were explored by the former Dadaist Hans Richter and the militant feminist Germaine Dulac, with Dulac completing The Seashell and the Clergyman, based on a a text by Antonin Artaud, a year before Buñuel and Dalí’s scandalous, but popular Un chien andalou. Though not a surrealist, Dulac’s film was as shocking as those produced by the members of the group.

(Amiens, 1882 – Paris, 1942)

The Seashell and the Clergyman

1927

Film, 35 mm, b&w, silent, 44’18”

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Purchase, 2009

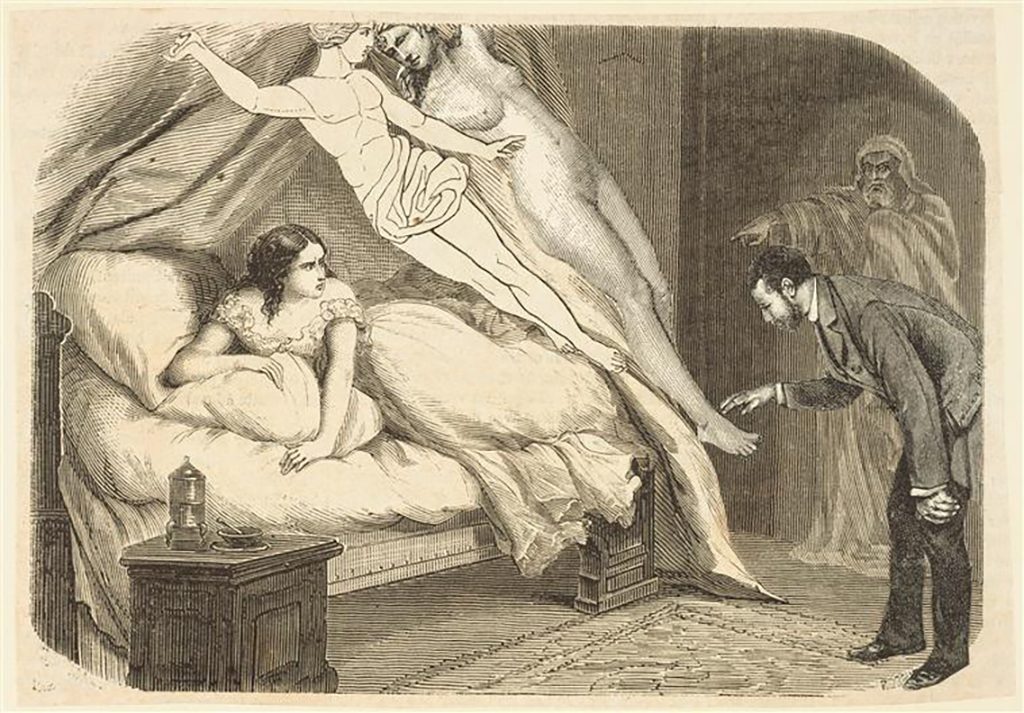

Surrealism + Film

A major theme in Surrealist film is the connection between dreams and desire. This exhibition presents clips from a variety of films where these themes appear. In 1928, French filmmaker Germaine Dulac worked with a script by Surrealist writer Antonin Artaud to create The Seashell and the Clergyman, a silent film about repressed desire. She explores the erotic fantasies of a priest who lusts after a general’s wife. Through slow motion shots, dissolves, blurred scenes and visual transformations, her film unfolds in dreamlike fashion. For Dulac, speaking in 1925, “If I did not do cinema, I would do politics… Women must have the vote.” In contrast, Man Ray’s The Starfish from 1928 is less coherent, mixing visual effects with symbolic images to create a disorienting Freudian dream. Based on a short poem by Surrealist writer Robert Desnos, Man Ray used cinematic distortions to reinforce the idea of lost love. Hans Richter’s film, Everything Revolves, Everything Turns, is an attempt to translate “the uninhibited fun-making of the fair into real fantasy.” Sharp juxtapositions of images, disconnected shifts in time and the recurring image of rotating objects symbolize the instability of Germany in the 1920s.

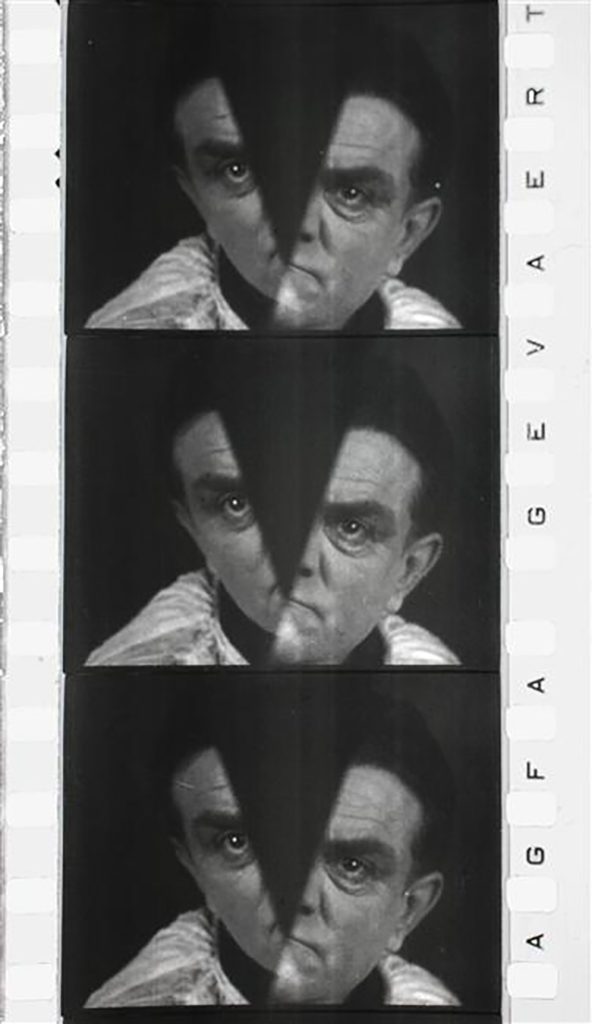

(Calanda, 1900 –Mexico City, 1983)

Un chien andalou

An Andalusian Dog

1929

Film, 35 mm, b&w, silent, 15’45”

Centre Pompidou, Párizs / Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Surrealism Film: Dalí & Buñuel

The tumultuous year of 1929 marked a crucial watershed for Dalí, who appeared on the scene with his colleague Luis Buñuel and their remarkable film Un Chien Andalou. Dalí’s arrival propels the Surrealist movement in new directions, giving birth to a second golden age of Surrealism. Buñuel knew they had created something shocking with the film, and expected the audience at the film’s premiere to riot, so he carried rocks in his pockets to defend himself. Instead, Un Chien Andalou was a huge hit, so popular the theater ran it for the next 8 months – and Buñuel and Dalí were invited to join the Surrealist movement. Un Chien Andalou unfolds with the irrational logic of a dream. Dalí and Buñuel decided to abandon a storyline, filming only these inexplicable dream sequences. There are many shocking scenes, including the slicing of an eyeball. Yet they were inspired by Buster Keaton comedies, so the pacing is exhilarating. Their second film, L’Age d’Or, a dark full-length comedy inspired by the Marquis de Sade, was one of the first movies made with sound in France. In Surrealist fashion, it attacked the hypocrisy of the Church, Family and State. When L’Age d’Or premiered in Paris, it was attacked by the League of Patriots. Ink was thrown at the screen, smoke bombs were thrown at the audience and Surrealist paintings in the lobby were attacked. The police confiscated all copies of L’Age d’Or, and it wasn’t shown again in public for 50 years.

Magritte and Variétés

The year 1929 saw the rapprochement of the French and Belgian surrealist groups. Variétés –revue mensuelle illustrée de l’esprit contemporain (the monthly illustrated magazine with a contemporary spirit), was founded in Brussels in May 1928 by Paul-Gustave Van Hecke. Urged on by his friend, E. L. T. Mesens, a Belgian artist, poet, and the founder of surrealism in Belgium, Van Hecke agreed to open the pages of his review to a special issue on surrealism. Published in June 1929, the special edition was distinguished by a red banner across the cover instead of the usual blue one. The review combines texts and illustrations by both French and Belgian surrealists. While the majority of contributions came from the French group, one Belgian painter received special attention: René Magritte. In 1927, Magritte and his wife, Georgette, had moved to Le Perreux-sur-Marne in the Paris suburbs in the hope of getting closer to André Breton. Magritte’s interest in philosophy, especially Hegel’s dialectic of bringing together two contradictory propositions, led him to move away from automatism, instead seeking poetic associations between objects. In 1929 Magritte wrote an article in La Révoution surréaliste in which he theorized his interest in the relationship between words and images. However, later that same year, Magritte and André Breton fell out over a dinner party dispute, when a small crucifix necklace worn by Georgette had enraged Breton’s anti-clericalist views.

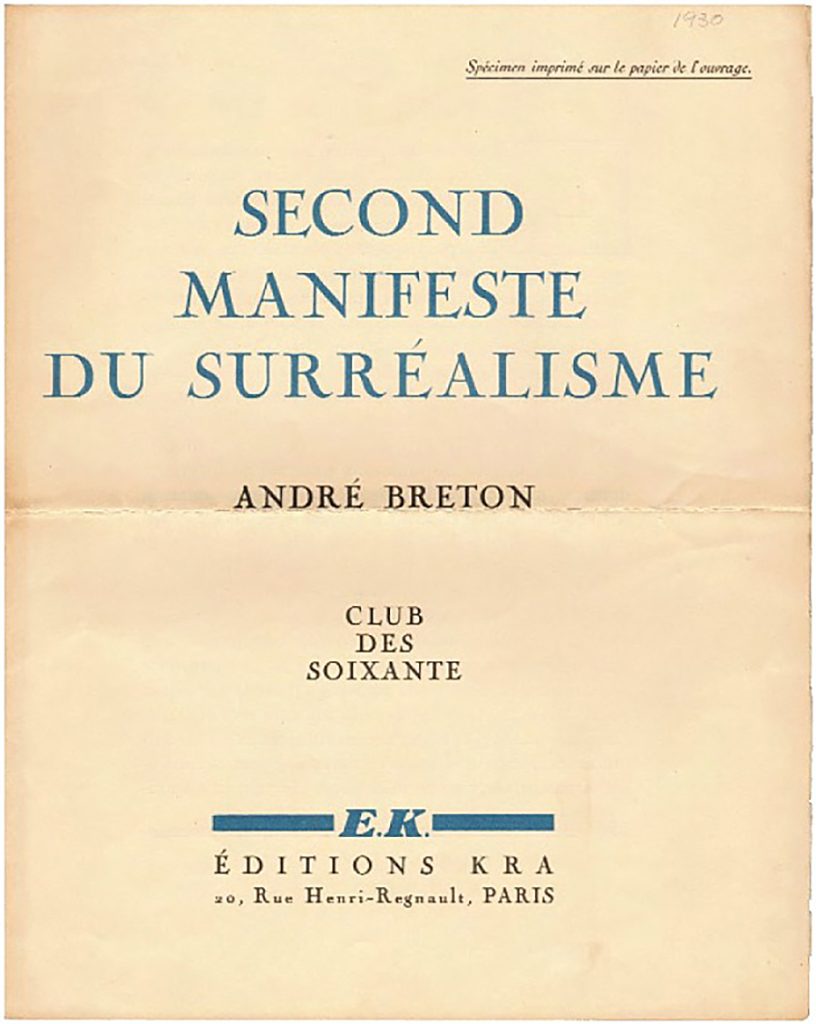

Documents

The first issue of the journal Documents was published in the spring of 1929. Led by Georges Bataille, the magazine was a crucible of surrealist dissent. In fact, Documents welcomed those who refused to support the movement’s shift in priorities towards political allegiance to the French Communist Party. Founded with museologist Georges Henri Rivière and writer, art critic Carl Einstein, the magazine ran for almost two years. Breton’s surrealism, with its taste for automatism, the unconscious, and the marvelous, was confronted with a new critical approach, based on photography. It was less attractive, aesthetically more brutal and arguably more rooted in reality, thanks to photographic illustrations by Jacques-André Boiffard, Eli Lotar, and Jean Painlevé. André Masson, who shared Bataille’s inclination for Neitzsche and Sade, was also close to the dissident group. In the Second Manifesto of Surrealism, published in the December 1929 edition of La Révolution surréaliste, Breton directed a venomous tirade at Bataille and his associates. The rebels retaliated by reappropriating the concept of a pamphlet written by the original surrealist group in 1924 that celebrated the death of Anatole France. Those attacked in the Second Manifesto (Antonin Artaud, Georges Limbour, Philippe Soupault, Roger Vitrac), joined forces with some dissidents (Raymond Queneau, Jacques Prévert) to publish Un Cadavre, in which they denounced Breton as a “false brother and false communist, false revolutionary but a true show-off.” In spite of these rifts, surrealism arose victorious in 1929. The movement’s restored vitality became evident when, at the beginning of 1930, Francis Ponge, Tristan Tzara, and Paul Nougé supported the first edition of a new surrealist journal entitled Le Surréalisme au service de la Révolution.

The Journals: Breton, Bataille & Surrealism at the Crossroads

The Surrealist Revolution, a surrealist journal published from 1924 to 1930, documented the first phase of the Surrealists’ creative exploration of automatism, dreams, the unconscious and psychoanalysis. By 1929, things were in flux. New groups like the Belgian Surrealists were expanding the topics associated with Surrealism, and the Paris group was at odds with itself. The Surrealist Revolution reflects arguments that began dividing the artists. Politically, many Surrealists suffered through the barbarism of the First World War. They saw the movement as a way of life. So they had a major challenge – how could an art movement help people get past societal violence? To some, merging with the communist party seemed like a necessary next step. This is what André Breton proposed in 1929, in the Second Manifesto of Surrealism. They therefore adopted a stance of collective activity and the absolute defense of freedom at all costs. There was dissent against Breton’s authority. Breton decided to clean house. In that Second Manifesto, he expels a number of key writers and artists from Surrealism, including the painter Masson and the photographer Boiffard. Breton attacked writer George Bataille most viciously. In turn, Bataille became the greatest threat to the Surrealist movement. He started a journal called Documents which became a beacon for dissident Surrealists. In response to Breton’s criticisms, in 1930 they published a pamphlet called Un Cadavre, or “A Corpse,” mocking Breton as a Christ-like martyr with a crown of thorns.

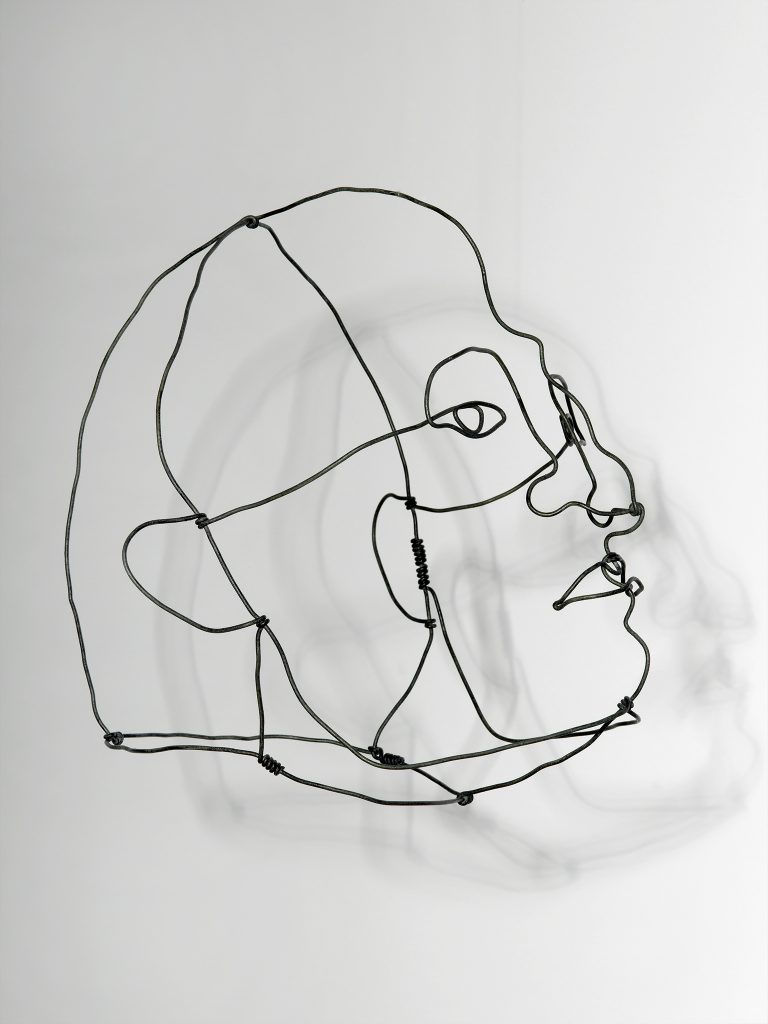

(Philadelphia, 1898 – New York, 1976)

Mask

[1929]

Wire

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Gift of the artist, 1966

Alexander Calder: Masks

Calder is best known for lyrical mobiles. Before he achieved these kinetic wonders, he was a young American sculptor who moved to Paris in 1926. There he met Miró and became associated with Surrealism. This is when he produced these first works of wire, a kind of “writing in space” where tension and precarious balance are given full expression. Further, they are weightless, defying the weight of sculpture, and transparent, defying the medium’s conventional density. This sculpting of emptiness influenced other sculptors, including Julio González, Pablo Picasso and Jacques Lipchitz, in 1928 and ’29. The success of these masks and the influence of Surrealism led Calder to produce his celebrated 1929 circus, with about a hundred miniature figures made of wire, that he could manipulate with strings and cranks.

Surrealist Objects and Desire

Among the many words one could use to describe the year 1929, the term “Sadean” seems most appropriate, since the writings of the Marquis de Sade imbue many surrealist works of the period. The spring saw the publication of a singular small volume of erotic poems by Louis Aragon and Benjamin Péret, simply titled 1929, illustrated with sexually explicit photographs by Man Ray. This clandestine publication was produced to finance the special surrealist edition of Variétés, also published in 1929. Objet désagréable (Disagreeable Object), one of Giacometti’s early “surrealist” works, shows the artist’s interest in Eros and Thanatos. Such works were considered the first examples of surrealist “objects,” an anti-sculptural concept, whereby assemblages of objects sought to provoke the viewer’s desire. The same conflicting concern with life and death inspired André Masson’s bold drawings of erotic scenarios planned for an unrealized publication of Sade’s novel, Justine.

(Stampa, 1901 – Coira, 1966)

Disagreeable Object

1931

plaster

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donated by Bruno, Odette Giacometti et Silvio Berthoud, 1988

The Cabinet of Curiosities

The Surrealists loved Cabinets of Curiosity. These were popular from the 16th through the 19th centuries, and housed objects from nature, geology, ethnography, and even historical relics. They were often more fantastic than scientific, and influenced the design of many surrealist exhibits. André Breton’s study was often described as a Cabinet of Curiosity, filled with surreal art, Oceanic and totemic artifacts. This final room of the exhibit pays homage to the Cabinets of Curiosity tradition. It features darker and more unusual examples of Surrealism, and work by dissident Surrealists. The surrealists often associated their approach to the object as erotic provocations. The centerpiece of this room is Giacometti’s unsettling Disagreeable Object, which seems to summon some sort of primordial fetishism. You will see collages by Max Ernst, Surrealist games, and André Masson’s [MAH-sun] violently erotic massacre drawings, some of which were inspired by the writings of the Marquis de Sade, an eighteen-century libertine writer rediscovered by the surrealists. You will also encounter the stark slaughterhouse photos by Eli Lotar, unveiling a little know side of Paris made to illustrate Bataille’s text “Abattoir.” And you will discover the menacing photos of monster-like figures by Jean Painlevé based on close-up images of marine creatures. Both brought new perspective to documentary photography.

Challenge to Painting

The German artist, Max Ernst, was a founding member of the Dada group. In 1921, at an exhibition of his collages at the Parisian gallery “Au sans pareil”, Ernst met the poet Paul Éluard. This led to his friendship with those who would go on to form the surrealist group. In the years that followed, Ernst’s work developed around themes such as ghostly apparitions, transfigured cities and forests, animals and birds, shells, and landscapes made of crystals. His technique also expanded to include collage, grattage (scratches) and frottage (rubbings), each of which came to have an enduring place in the surrealist visual vocabulary. In December 1929, Ernst published his first collage novel, La Femme 100 têtes (The Hundred Headless Woman), made up of 147 plates reproducing collages of nineteenth-century engravings. If cubist papiers collés were compositional tools, and if irreverent Dadaist collages were an attack on art itself, the most remarkable endeavour of Ernst’s surrealist collages was to pose a “challenge to painting,” the title of an important March 1930 essay by Louis Aragon devoted to the technique of collage. These experiments are similar to those of the Catalan artist Joan Miró, who settled in Paris in the mid-1920s. Miró imagined a dreamlike and poetic world that was far from the surrealist interest in automatism. Nevertheless, André Breton called Miró “the most beautiful feather in the surrealist cap.” Aragon’s “challenge” was echoed by Miró’s own statement calling for “the assassination of painting.” In this way, Miró developed a form of “anti-painting.”

(Brühl, 1891 – Paris, 1976)

Two bodyless bodies position themselves in parallel to their body whilst falling from the bed and the curtains, like ghosts without ghost.

1929

Cut-out engravings

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Donated by Mr. Carlo Perrone, 1999

Ernst: Collage Novel

Max Ernst’s collage novel of 1929 was a revelation. The title, La Femme 100 Têtes, is a double entendre. When read aloud in French, it can mean either “the hundred-headed woman” or “the headless woman.” This was the first collage novel by Ernst. Nine chapters unfold in a very loose narrative. Ernst collaged images from 19th century magazines, encyclopedias and trivial novels, to create a new and dreamlike narrative. Scientific illustrations, religious visions and pulp fiction merge, accompanied by equally strange captions. By juxtaposing unrelated images, Ernst creates a provocative dream world that invites the viewer to participate, and create a story. La Femme 100 Têtes is where Max Ernst introduced his bird alter ego – Loplop – into his art. This bird appears in all three of the Ernst paintings in this exhibition. In the book’s introduction, André Breton proclaimed that, “One awaited a book that avoids all parallels with other books – aside from their mutual use of ink and type… The Hundred-Headed Woman will be preeminently the picture book of our day… Such is our idea of progress.”

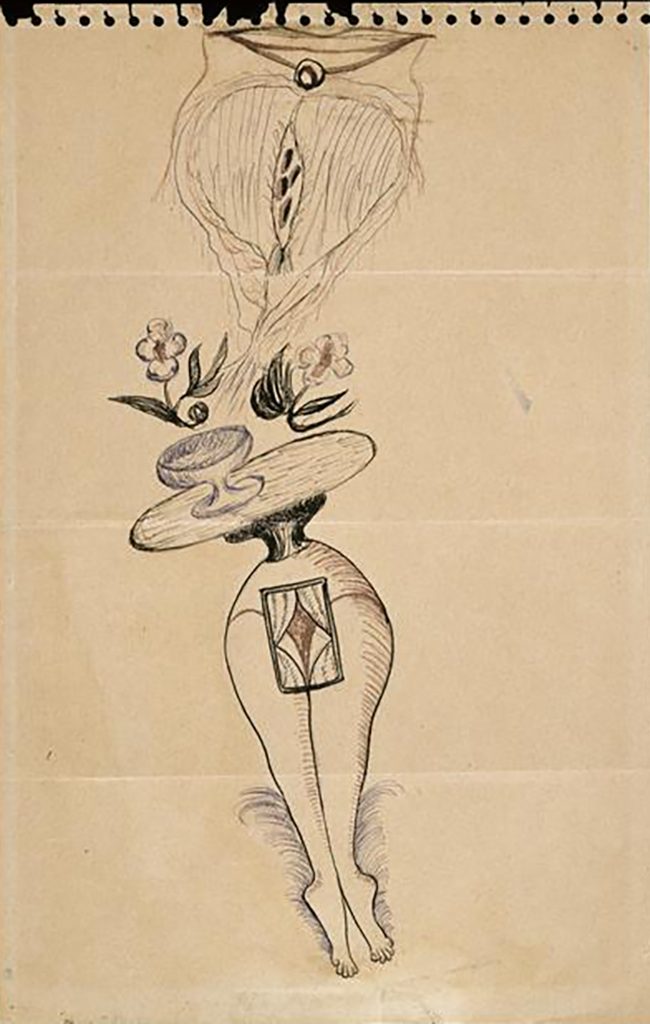

Cadavre exquis

Exquisite Corpse

[1927]

Graphite and colored pencil on paper

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Purchase to Mme. Aube Breton Elléouët in 1980.

Game Playing – The Exquisite Corpse The Surrealists believed profound discoveries can be made during simple activities that distract the mind. They distrusted ideas that were rational or ego-driven, so they embraced game playing. Just as automatic writing was a weapon to use against narrative logic, collective drawing challenged the idea of an ‘individual artist.’ The “blind” execution of a work by three or four different hands drew upon the unconscious, childhood and humor. Based on a 19th century children’s game called “Consequences,” the “exquisite corpse” can be played through writing or visual images. Three or four people gather at a table and a sheet of paper is folded. The first person draws the head of a creature, then folds the paper so the next person only sees the lines that show where the neck is. The second person draws the shoulders and chest, and so on. In the end, an image of a new creature is created collectively. Often, the “exquisite corpse” surprises, because of its uncanny coherence. Max Ernst called this collaborative process “mental contagion.” These drawings reveal the Marvelous, that spontaneous form of beauty the Surrealists prized over everything else. Between 1924 and 1949, the surrealists produced more than 200 exquisite corpses.

See also: Dalí’s Exquisite Corpse

Director’s Conclusion

Thank you for viewing our online exhibition, “Midnight in Paris, Surrealism at the Crossroads, 1929.” I hope you feel the creative energy, the excitement, and the yearning of that time. Consider if we are again in a moment like that one, and if so, what can we make of this opportunity?

PlayList

To capture the spirit of Paris in 1929, we selected musical pieces to set the mood of the cafes and nightclubs of late 1920s Paris.

- Cole Porter: Let’s Do It. Artists: Cole Porter, The John Wilson Orchestra, John Wilson, Anna Jane Casey; Album: Cole Porter in Hollywood

- La Conga Blicoti. Artist: Josephine Baker; Album: Collection disques Pathe

- Let’s Do It. Artist: Brazilian Tropical Orchestra; Album: The American Songbook: Cole Porter

- Non, je ne regretted rien. Artist: Édith Piaf; Album: Eternelle

- You Do Something to Me. Artist: Brazilian Tropical Orchestra; Album: The American Songbook: Cole Porter

- I Love Paris. Artist: Cole Porter. Album: Éxitos Inolvidables De Cole Porter

- Queen Of Terre Haute (You’ve Got That Thing/You Don’t Know Paris/You Do Something To Me). Artist: Julie Wilson. Album: Cole Porter Songbook

- What Is This Thing Called Love. Artist: Cole Porter; Album: Classic Movie & Broadway Show Tunes From Rare Piano Rolls

- Blue Skies. Artist: Joséphine Baker; Album: Black Venus CD1

- Bye Bye Blackbird. Artist: Joséphine Baker; Album: The Creole Goddess

- Happy End, Act III: Surabaya Johnny. Artist: Kurt Weill, Marianne Oswald, Pierre Chagnon Orchestra; Album: Weill: Die Dreigroschenoper – Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny – Songs (1928-1944)

- Mes soeurs n’aimez pas les marins. Artist: Marianne Oswald; Album: Jean Cocteau et ses interprètes – Collection Pathé

The above songs are located on these 3 audio files

Artist Quotes

To bring to life some of the personality and conflicting views of the over 20 artists included in the exhibit, we selected a variety of quotes by each concerning art. Through these quotes, some of the aspirations and arguments behind the work come to life.

- “The idea of Surrealism aims quite simply at the total recovery of our psychic force by a means which is nothing other than the dizzying descent into ourselves. ” Breton

- “My paintings are the opposite of dreams.” Magritte

- “A whole world is contained in the drop of water which trembles on the edge of a leaf; but it is there only when an artist and a poet have the gift of seeing it in its immediacy.” Masson

- “The element of surprise in the creation of a work of art is the most important factor.” Tanguy

- “My wanderings, my unrest, my impatience, my doubts, my beliefs, my hallucinations, my loves, my outbursts of anger, my revolts, my contradictions, my refusals to submit to any discipline. My work is like my conduct.” Ernst

- “For we Surrealists, we are not quite artists, nor are we exactly true men of science, we are the caviar, and caviar, believe me, is the very extravagance and intelligence of taste. Dalí

- “The only thing that’s clear to me is that I intend to destroy, destroy everything that exists in painting. I have an utter contempt for painting. The only thing that matters to me is the spirit itself.” –Miró

- “I had surrendered all my activity and hope to surrealism.” Buñuel

- “The great adventure is to see something unknown emerge each day, in the same face that is greater than all the trips around the world.” Giacometti

- “How does art come into being? Out of volumes, motion, spaces carved out within the surrounding space, the universe.” Calder

Organized by the Centre Pompidou, Paris, and The Dalí Museum, Midnight in Paris, 1929, and was curated by Dr. William Jeffett, Chief Curator of Special Exhibitions at The Dalí Museum, and Didier Ottinger, Deputy Director of the Musée national d’art moderne at the Centre Pompidou. The Dalí Museum’s unique installation was adapted from a selection of works organized by Dr. Ottinger and previously exhibited at the Palazzo Blu in Pisa and the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest.

Midnight in Paris: Surrealism at the Crossroads, 1929 is sponsored by:

Mrs. Jean-François Rossignol

Mrs. Timothy R. Ranney

St. Pete–Clearwater International Airport